> Daily archaeology news from the Internet (on www.archaeologica.org).

> Latest publications : North Africa, Sahara, West Africa - in french

> Latest publications : Central Africa - in french

> African-archaeology.net news archives : 2011 - 2010 - 2008 - 2007 - 2006 -

|

Satellites unearthing ancient Egyptian ruins (Egypt) 23 December 2008 (CNN) -- Archaeologists believe they have unearthed only a small fraction of Egypt's ancient ruins, but they're making new discoveries with help from high-tech allies -- satellites that peer into the past from the distance of space. "Everyone's becoming more aware of this technology and what it can do," said Sarah Parcak, an archaeologist who heads the Laboratory for Global Health at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. "There is so much to learn." Images from space have been around for decades. Yet only in the past decade or so has the resolution of images from commercial satellites sharpened enough to be of much use to archaeologists. Today, scientists can use them to locate ruins -- some no bigger than a small living room -- in some of the most remote and forbidding places on the planet. In this field, Parcak is a pioneer. Her work in Egypt has yielded hundreds of finds in regions of the Middle Egypt and the eastern Nile River Delta. Parcak conducted surveys and expeditions in the eastern Nile Delta and Middle Egypt in 2003 and 2004 that confirmed 132 sites that were initially suggested by satellite images. Eighty-three of those sites had never been visited or recorded. In the past two years, she has found hundreds more, she said, leading her to amend an earlier conclusion that Egyptologists have found only the tip of the iceberg. "My estimate of 1/100th of 1 percent of all sites found is on the high side," Parcak said. These discoveries are of no small significance to the Egyptian government, which has devoted itself anew to protecting archaeological sites from plunder and encroachment. The Supreme Council of Antiquities has restricted excavation in the most sensitive areas along the Nile -- from the Great Pyramids at Giza on the outskirts of Cairo to the carvings of Ramses II in the remote south. Antiquities officials hope the move will encourage more surveys in the eastern Nile Delta in northern Egypt, Parcak said, where encroaching development in the burgeoning nation of 82 million poses the greatest threat to the sites. Old and modern methods Parcak's process weds modern tools with old-fashioned grunt work. The archaeologist studies satellite images stored on a NASA database and plugs in global positioning coordinates for suspected sites, then tramps out to see them. Telltale signs such as raised elevations and pot shards can confirm the images. As a result, the big picture comes into view. "We can see patterns in settlements that correspond to the [historical] texts," Parcak said, "such as if foreign invasions affected the occupation of ancient sites. "We can see where the Romans built over what the Egyptians had built, and where the Coptic Christians built over what the Romans had built. "It's an incredible continuity of occupation and reuse." The flooding and meanders of the Nile over the millennia dictated where and how ancient Egyptians lived, and the profusion of new data has built a more precise picture of how that worked. "Surveys give us information about broader ancient settlement patterns, such as patterns of city growth and collapse over time, that excavations do not," said Parcak, author of a forthcoming book titled "Satellite Remote Sensing and Archaeology." The vagaries of climate in the region make satellite technology advantageous, too. "Certain plants that may indicate sites grow during certain times of the year," Parcak said, "while sites may only appear during a wet or dry season. This is different everywhere in the world." Archaeologists working in much more verdant climates, such as Cambodia and Guatemala, also have used the technology to divine locations of undiscovered ruins. They have been able to see similarities between the vegetation at known sites and suspected sites that showed up in fine infrared and ultraviolet images covering wide areas of forbidding terrain. "For the work I do [in Egypt], I need wet season images as wet soil does a better job at detecting sites with the satellite imagery data I use," Parcak said. "I can pick the exact months I need with the NASA satellite datasets." Benefits of a bird's-eye view Remote subsurface sensing has been used in archaeology in one form or another for years, though the term "remote" doesn't necessarily imply great distance. Typically, a surveyor has wheeled a sensing device over a marked-out area to determine what lies below. The sensing devices employ any of an array of technologies, such as Ground Penetrating Radar. They bounce signals off objects below the surface and translate the data into images that a scientist's trained eye can decipher. Multispectral imaging encompasses technologies that "see" what the human eye can't, such as infrared and ultraviolet radiation. Scientists have used it for years to study the Earth's surface for a variety of purposes. Until resolution of these images improved, though, the only way to produce a sharp image was to be relatively close to the ground. For those lugging unwieldy gear across jungle and desert, an effective bird's-eye view can change the world. It lets them leave behind the days and days of meticulous "prospecting" and get results from airplane-mounted sensors or, later on, a flyover by an advanced satellite. One of the most advanced is called QuickBird, which has been in orbit since 2001 and can provide high-resolution images of 11-mile-wide swaths. The satellite can collect nearly 29 million square miles of imagery data in a year, according to DigitalGlobe, which developed and operates QuickBird. The company, based in Longmont, Colorado, is working on an upgrade. WorldView-2, to be launched in 2009, will offer sharper resolution of visual and multispectral images than QuickBird, according to the company's Web site. In the end, though, a tool is only as useful as its wielder. "Most of the advances have come through processing on the ground by end users such as Dr. Parcak," said DigitalGlobe spokesman Chuck Herring. Source : http://www.cnn.com/2008/TECH/science/12/23/satellites.archaeology.egypt/

| |

|

Pair of tombs discovered in Egypt (Egypt) 23 December 2008 Egyptian archaeologists say they have discovered a pair of 4,300-year-old tombs that indicate a burial site south of Cairo is bigger than expected. The tombs at the Saqqara necropolis belong to two officials from the court of the Pharaoh Unas, Egypt's antiquities chief said. One was for the official in charge of quarries used for building pyramids, the other for the head of music. Hieroglyphics decorate the entrances of both the newly discovered tombs. Zahi Hawass, Egypt's top archaeologist, told reporters that the tombs represented a "major" find. "The discovery of the two tombs are the beginning of a big, large cemetery," he said. New discoveries are frequently made at Saqqara, including the unearthing of the remains of a pyramid in November. Mr Hawass said 70% of Egypt's ancient monuments remain buried. "We are continuing our excavation and we are going to uncover more tombs in the area to explain the period of dynasty five and dynasty six," he added, referring to a period more than 4,000 years ago. The contents of the newly found tombs have long since been stolen, Mr Hawass said. The entrance of the tomb of the official in charge of music, Thanah, shows carved images of her smelling lotus flowers. The other official whose tomb was discovered, Iya Maat, oversaw the extraction of granite and limestone from Aswan and other materials from the Western Desert for the construction of nearby pyramids. Source : http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/7796675.stm

| |

|

Ancient African Exodus Mostly Involved Men, Geneticists Find (Africa) 19 December 2008 Modern humans left Africa over 60,000 years ago in a migration that many believe was responsible for nearly all of the human population that exist outside Africa today. Now, researchers have revealed that men and women weren’t equal partners in that exodus. By tracing variations in the X chromosome and in the non-sex chromosomes, the researchers found evidence that men probably outnumbered women in that migration. The scientists expect that their method of comparing X chromosomes with the other non-gender specific chromosomes will be a powerful tool for future historical and anthropological studies, since it can illuminate differences in female and male populations that were inaccessible to previous methods. While the researchers cannot say for sure why more men than women participated in the dispersion from Africa—or how natural selection might also contribute to these genetic patterns—the study’s lead author, Alon Keinan, notes that these findings are “in line with what anthropologists have taught us about hunter-gatherer populations, in which short distance migration is primarily by women and long distance migration primarily by men.” These findings are published in Nature Genetics. Source : http://www.newswise.com/articles/view/547619/?sc=rssn

| |

|

Sudan statue find gives clues to ancient language (Sudan) 16 December 2008 KHARTOUM, Dec 16 (Reuters) - Archaeologists said on Tuesday they had discovered three ancient statues in Sudan with inscriptions that could bring them closer to deciphering one of Africa's oldest languages. The stone rams, representing the god Amun, were carved during the Meroe empire, a period of kingly rule that lasted from about 300 BC to AD 450 and left hundreds of remains along the River Nile north of Khartoum. Vincent Rondot, director of the dig carried out by the French Section of Sudan's Directorate of Antiquities, said each statue displayed an inscription written in Meroitic script, the oldest written language in sub-Saharan Africa. "It is one of the last antique languages that we still don't understand ... we can read it. We have no problem pronouncing the letters. But we can't understand it, apart from a few long words and the names of people," he told reporters in Khartoum. Sudan has more pyramids than neighbouring Egypt, but few people visit its remote sites, and repeated internal conflicts have made excavation difficult. Rondot said the dig at el-Hassa, the site of a Meroitic town, had uncovered the first complete version of a royal dedication, previously found only on fragments of carvings from the same period. He said experts were still trying to work out the meaning of the words by comparing them with broken remnants of similar royal dedications in the same script. "It's an important discovery ... quite an achievement," Rondot said. The statues were found three weeks ago under a sand dune at the site of a temple to the god Amun, an all-powerful deity represented by the ram in Sudan. The site is close to Sudan's Meroe pyramids, a cluster of more than 50 granite tombs 200 kms (120 miles) north of the capital that are one of the main attractions for Sudan's few tourists. Rondot said the dig, funded by the French foreign ministry, would also provide vital information on the reign of a little-known king, Amanakhareqerem, mentioned in the inscriptions on the rams. "Before we started the dig we only had four documents in his name ... We don't even know where he was buried," he said. "We are beginning to understand the importance of that king." (Editing by Katie Nguyen and Tim Pearce) Source : http://africa.reuters.com/wire/news/usnLG432974.html

| |

|

From brief limelight to obscurity (Sudan) 3 December 2008 It's full speed ahead for the Sudanese hydroelectric project which will flood the ancient kingdom of Meroe, says Jill Kamil Technology and archaeology are at odds again. The Meroe High Dam, otherwise known as the Multi-Purpose Hydro Project or Hamdab Dam, is well underway -- and the archaeological remains of the ancient African kingdom of Meroe which developed along the upper reaches of the Nile is destined to oblivion. The purpose of the dam being constructed close to the Fourth Cataract, about 200 kilometres north of Khartoum, is to generate electricity. It is the largest hydropower project currently under construction in Africa. With a length of some nine kilometres, and a crest height of up to 67 kilometres it is reminiscent of the High Dam at Aswan constructed in the 1960s. It too is designed with a concrete-faced rock-fill barrage on each river bank, the left river channel with a clay core, and the right with a live water section. Once completed, its 200-kilometre long reservoir, with a capacity to produce 1,250 megawatts of power, will displace 50,000 people and inundate countless archaeological sites including Meroe in the African kingdom of Kush, sub-Saharan Africa's earliest urban civilisation. Meroe, which is situated at a strategic location in the region known as Butana, enjoyed stability when Kushites moved the centre of their government there from the old capital of Napata (Nuri) -- which gradually declined but nevertheless retained its sacred status. The new capital grew and flourished contemporaneously with the Persian rule of Egypt, the later Egyptian dynasties, and the Ptolemaic and Roman periods, which is to say for nine centuries. The Meroitic Kingdom controlled trade routes -- east to the Red Sea, west to Kordofan and Darfur, north to Egypt, and south to central Africa -- and its sphere of influence spread even as far north as the island of Philae within sight of Aswan. Traders found markets for their ivory, gold, ebony and live animals, and the names of its kings have been documented by historians, even down to the approximate lengths of their reigns. The first century AD marked the peak of Meroitic ascendancy, and its flourishing economy is reflected in the advanced culture seen in the superior quality of Meroitic crafts, particularly fine work in jewellery and pottery. Then started a slow decline, precipitated first by the inroads of two desert peoples, the Blemmyes and the Noba; then in competition with the new kingdom of Axum in northern Ethiopia when it emerged as the largest commercial centre in north-east Africa; and finally, in about 350 AD, when the first Christian king of Axum led a campaign into the region and defeated Meroitic troops near the confluence of the White Nile and the Atbara. By the beginning of the fourth century Meroe was no more. It fell to ruin and became a part of legendary history. Meroe was not included among the sites studied and protected when the High Dam at Aswan was built in the 1960s and Nubia was subjected to the largest archaeological salvage operation ever known, because it did not fall within the threatened area. Now the area is threatened by the Meroe High Dam Project which was signed in 2002 and 2003. Despite numerous efforts to curb the construction of dams along the Upper Nile by the board of the Nubian Society (which represents a body of the international archaeological community working closely with the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums), and contact with major stakeholders in Sudan to give due consideration to potential damage to a major heritage sites, the project has moved ahead. Chinese, German and French contractors began work on river diversion and construction of the concrete dams early in 2004. The reservoir impounding started in mid-2006, and the land for the reservoir was marked out. The local population nearest the construction site were moved, without prior warning, to a new location. Flooding started in August 2007. By the end of this year large segments of the land will be underwater, and when the level in the reservoir reaches 300 metres all ten generating units will be operational. This is scheduled before the end of 2008 or the beginning of 2009. Time is running out and archaeologists are watching closely to see what they can rescue before it is too late. In his paper at the Eleventh Conference for Nubian Studies in Warsaw, Derek Welsby of the British Museum, president of the International Association of Nubian Studies, said that in the past the assumption that this section of the Upper Nile was an inhospitable region led archaeologists to consider it a marginal zone avoided by the major cultures which flourished in the Nile Valley to the north and south. "The current work," he said, "is causing a radical rethinking of this position. Vast numbers of archaeological sites are now known". He outlined the work of the many archaeological missions active in the Fourth Cataract region, and summarised their achievements in casting light on the Paleolithic occupation, through the Neolithic, Kerma and Kushite periods, to the post-Meroitic, Mediaeval and post-Medieval remains. "The region may be rocky and inhospitable, but archaeologists now know that it was not a marginal zone avoided by the major cultures," he said. In fact the Fourth Cataract region is rich in archaeology, and it is unfortunate that, unlike the UNESCO project of the 1960s when the High Dam was built at Aswan, Sudanese Nubia has no monuments of the calibre of Abu Simbel to attract world attention to what is being done. The half-dozen Sudanese and foreign missions working in the threatened area have already pin-pointed hundreds of settlements and cemeteries spanning four millennia, and lithic artefacts, rock art, pottery, and even a granite pyramid -- the only one so far known in Sudan -- have been found, not to mention mediaeval Christian remains and Islamic cemeteries. The idea of a Nile dam at the Fourth Cataract is not new. During the first half of the 20th century, the authorities of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan proposed it several times with a view to creating conditions for cotton-growing and providing flood protection for the lower Nile Valley. After Sudan gained independence in 1956, the idea of a dam in Sudan was abandoned in favour of the High Dam at Aswan. In 1979, under the government of President Nimeiri, the plan was revived with a view to producing hydro-electricity to meet Sudan's rising demand. Feasibility studies were carried out, but the project stalled for insufficient funding and lack of investor interest. The situation changed when the country started exporting oil in commercial quantities in the years 1999/2000, when improved credit-worthiness brought an influx of foreign investment and contracts for the construction of the Meroe Dam Project. While the inevitable loss of sites beneath the Meroe Dam lake is to be regreted, the project has provided the stimulus for archaeological research and that is a good thing. Thanks to the wealth of data resulting from various surveys, particularly for the Meroitic and later periods, attention has been drawn to what was hitherto a neglected area and field of investigation. Unexpectedly, evidence has come to light of formally and legally stratified society in Meroitic Nubia, with royalty at the top of the scale and slaves at the bottom. The high status of women within the royal families is now well attested both for Kush and for Christian Nubia. And as for slaves in Islamic times, while a number were exported, most of them appear to have lived in the households of the owners and, because of their attachment to families, were given humane consideration at the time of death and buried with the same ritual considerations as free men. Meroe is already attracting tourists. Indeed, it is somewhat reminiscent of the last days of Egyptian Nubia before the completion of the High Dam at Aswan. The area is within easy reach of Khartoum, only a couple of hours away by car, and visitors are coming to see contractors at work on the reservoir and visit those sites that lie above the expected high waterline of the lake. In fact, even as this article goes to press, I hear that tourist infrastructure is being provided in some areas, that a pipeline is bringing fresh water to the site, and that a small visitor's centre is being built to provide the necessary facilities. Source : http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2008/925/heritage.htm

|

Stone tools found at the archaeological site of Gademotta, in the Ethiopian Rift Valley, were likely crafted by the earliest Homo sapiens, according to a study published in December 2008. Stone tools found at the archaeological site of Gademotta, in the Ethiopian Rift Valley, were likely crafted by the earliest Homo sapiens, according to a study published in December 2008.The tools were uncovered in the 1970s, but it was not until this year that new dating techniques revealed the tools to be far older than the oldest known Homo sapien bones, which are around 195,000 years old. |

Humans 80,000 Years Older Than Previously Thought ? (Ethiopia) 3 December 2008 Modern humans may have evolved more than 80,000 years earlier than previously thought, according to a new study of sophisticated stone tools found in Ethiopia. The tools were uncovered in the 1970s at the archaeological site of Gademotta, in the Ethiopian Rift Valley. But it was not until this year that new dating techniques revealed the tools to be far older than the oldest known Homo sapien bones, which are around 195,000 years old. Using argon-argon dating—a technique that compares different isotopes of the element argon—researchers determined that the volcanic ash layers entombing the tools at Gademotta date back at least 276,000 years. Many of the tools found are small blades, made using a technique that is thought to require complex cognitive abilities and nimble fingers, according to study co-author and Berkeley Geochronology Center director Paul Renne. Some archaeologists believe that these tools and similar ones found elsewhere are associated with the emergence of the modern human species, Homo sapiens. "It seems that we were technologically more advanced at an earlier time that we had previously thought," said study co-author Leah Morgan, from the University of California, Berkeley. The findings are published in the December issue of the journal Geology. Complicated family tree The lack of bones at Gademotta makes it difficult to determine exactly who made these specialist tools and whether this really pushes the date of the beginning of modern humans, or Homo sapiens, back 80,000. Some archaeologists believe it had to be Homo sapiens while other experts think that our earlier ancestors may have had the required mental capability and manual dexterity. Regardless of who made the tools, the dates help to fill a key gap in the archaeological record, according to some experts. "The new dates from Gademotta help us to understand the timing of an important behavioral change in human evolution," said Christian Tryon, a professor of anthropology from New York University, who wasn't involved in the study. If anything, the story has now become more complex, added Laura Basell, an archaeologist at the University of Oxford in the U.K. "The new date for Gademotta changes how we think about human evolution, because it shows how much more complicated the situation is than we previously thought," Basell said. "It is not possible to simply associate specific species with particular technologies and plot them in a line from archaic to modern." Desirable Location Gademotta was an attractive place for people to settle, due to its close proximity to fresh water in Lake Ziway and access to a source of hard, black volcanic glass, known as obsidian. "Due to its lack of crystalline structure, obsidian glass is one of the best raw materials to use for making tools," Morgan explained. In many parts of the world, archaeologists see a leap around 300,000 years ago in Stone Age technology from the large and crude hand-axes and picks of the so-called Acheulean period to the more delicate and diverse points and blades of the Middle Stone Age. At other sites in Ethiopia, such as Herto in the Afar region northeast of Gademotta, the transition does not occur until much later, around 160,000 years ago, according to argon dating. This variety in dates supports the idea of a gradual transition in technology. "A modern analogy might be the transition from ox-carts to automobiles, which is virtually complete in North America and northern Europe, but is still underway in the developing world," said study co-author Renne, who received funding for the Gadmotta analysis from the National Geographic Society's Committee for Research and Exploration. (The National Geographic Society owns National Geographic News.) Morgan, of UC Berkeley, speculates that the readily available obsidian at Gademotta may explain why the technological revolution occurred so early there. Source : http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2008/12/081203-homo-sapien-missions.html

|

|

The Long Road to Modernity - Middle Stone Age (Ethiopia) 1 December 2008 Most experts agree that Homo sapiens arose in Africa about 200,000 years ago and had more brainpower than earlier hominid species. But it's a matter of debate whether modern humans got smarter in one big cognitive leap or gradually developed their greater intelligence. New dating of an important hominid site in Ethiopia suggests that the road to advanced cognition was long and winding. Anthropologists and archaeologists rely on stone tools and other artifacts to gauge the sophistication of ancient humans. About 1.7 million years ago in Africa, Homo erectus, an ancestor of modern humans, started using large hand axes and cleavers. This know-how spread to Asia and Europe and remained cutting-edge technology for well over a million years. Eventually, however, it gave way to the Middle Stone Age, which featured smaller and more sophisticated blades and spearheads. Many researchers have assumed that these weapons and tools were made by modern humans, because nearly all of them have been found at sites dated later than 195,000 years ago, the age of the oldest known H. sapiens fossils. That would imply a big cognitive leap on the part of modern humans, as they would have essentially developed a complex technology as soon as they arrived on the scene. But not all evidence jibes with this theory. In the 1990s, for example, archaeologists dated a Middle Stone Age site in Ethiopia called Gademotta to 235,000 years ago--implying that the technology had been maturing for a while before the arrival of modern humans--although the accuracy of that dating has been questioned. A second site, Kapthurin in Kenya, was more reliably dated in 2002 to 285,000 years ago, but researchers have been very reluctant to accept just one site as evidence that the Middle Stone Age started so early. Both sites are in Africa's volcanic Rift Valley, the birthplace of many hominid species. Now two geochronologists from the University of California, Berkeley, Leah Morgan and Paul Renne, have redated Gademotta using the argon-argon method, an improved technique for dating volcanic rock that is considered more accurate than the potassium-argon method previously employed at the site. The new results, reported in this month's issue of Geology, push the artifacts at Gademotta back to at least 280,000 years ago, essentially the same age as those at Kapthurin. Morgan and Renne suggest that the early dates at both Gademotta and Kapthurin indicate that the tools were probably not invented by modern humans but rather by ancestral hominids intermediate between H. erectus and H. sapiens. A few fossils that might represent such ancestors have been found in Africa over the past decades and are thought to be between 400,000 and 200,000 years old. Sally McBrearty, an anthropologist at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, and a leader of the excavations at Kapthurin, says that the new Gademotta dates provide "solid confirmation" of the early appearance of Middle Stone Age technology. And Christian Tryon, an anthropologist at New York University, says that the "major behavioral changes" represented by the early invention of these sophisticated tools may have even helped stimulate the advances in cognition that would become the hallmark of modern humans. Source : http://sciencenow.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2008/1201/1

| |

|

Clues to why modern humans migrated... (South Africa) 21 November 2008 In a cave 70 000 years ago, something strange was beginning to happen. The occupants, who once lived in the cave, were behaving differently from their forefathers. They were producing some of the first examples of jewellery and developing new technologies that were to give them an edge in years to come. It wasn't an isolated event, across the African continent, the same thing was happening among bands of hunter gatherers from the Western Cape to Morocco. What sparked this, no one knows. It was so dramatic that some believe it might originally have been caused by a sudden change in the structure of our ancestor's brains. That cave is Sibudu Cave, situated near Tongaat, in KwaZulu Natal, and it is here that an international team of scientists are unearthing the clues to this event and are trying to make sense of it all. Their findings were published as part of a larger southern African dating project, in the journal Science at the end of October. What they found in the cave were minute seashells that were likely strung together to make a necklace, bone arrowheads and the residues of what is possibly the earliest example of glue. Also present were finely-crafted stone tools never seen before in earlier deposits. These tools were probably parts of spearheads. To archaeology professor Lyn Wadley of Wits University this haul reveals the earliest workings of what she calls complex cognitive behaviour. In these artefacts, dug from the bottom of the cave are the signs of some of humans' earliest known attempts at making jewellery. "We now know that these beads are 70 000 years old. "Similarly-aged perforated seashells were discovered in Blombos Cave, Western Cape," Wadley explained, from Sibubu where she is continuing with her dig. These changes happened in the space of about 5 000 years, an extraordinary short period of time, in the span of evolution. Wadley is part of a team that includes Dr Zenobia Jacobs and Professor Richard "Bert" Roberts from the University of Wollongong, Australia. For these Australian scientists, what has come out of Sibubu cave could help explain what motivated the first modern humans to migrate out of Africa, about 80 000 years ago, and later island hop from Asia to Australia. New technological know how gave the migrating humans an advantage. "With the perforated seashells we see people demonstrating that they are part of a group, or a particular status within that group. "The use of personal ornamentation is evidence of symbolic behaviour even today," said Wadley. The team has also found traces of red ochre which could have been used to paint ornaments. Helping the team in their research was some high-tech gadgetry that aided them in piecing together how those cave dwellers lived all those years ago. With the help of a microscope the academics found traces of residue on some of the stone tools. It turned out to be plant gum mixed with red ochre, and was probably glue. "Making such glue and using it to attach a spearhead to a shaft requires complex cognitive abilities because it involves holding many things in mind during the process," Wadley said. Earlier this year Dr Lucinda Backwell of the Bernard Price Institute for Palaeontological Research revealed that Sibubu Cave had produced what was believed to be the first bone arrow head, aged between 65 000 and 62 000 years. The arrowheads may have been used for hunting blue duiker and plains game, then found close to the cave. Again Wadley stressed that making such arrowheads and figuring out the technology that goes with manufacturing bows would have required a leap in thinking. The team was even able to ascertain through studying burnt charcoal what these early humans were using for firewood. In the ancient ash were found charred bones, many of them smashed so as to get at the nutritious marrow inside. A microscopic study of the sediments in the cave revealed seeds that suggested that bundles of reeds were used as early mattresses. It wasn't just at Sibubu that early humans were showing the innovation that today we take for granted. Similar artefacts have been found in Morocco and at other archaeological sites in South Africa and Wadley believes these developments occurred independently of each other. As to what triggered this change in early human behaviour, Wadley suggests that it might be up to academics in other scientific fields to answer that question. "It might have been some sort of genetic mutation that made early people able to think in a modern way, but this suggestion needs to be followed up by someone other than an archaeologist," she said. Source : http://www.int.iol.co.za/index.php?set_id=1&click_id=588&art_id=vn20081121054843530C280787

| |

|

New pyramid found at Saqqara (Egypt) 20 November 2008 The newly discovered subsidiary pyramid of queen Sesheshet, mother of King Teti I, the founder of the Sixth Dynasty, is another clue to understand more such an enigmatic dynasty as Nevine El-Aref writes Last week the announcement of the discovery at the Saqqara necropolis of the 4,300-year-old subsidiary pyramid of Queen Sesheshet, mother of King Teti I, the founder of the Sixth Dynasty, caught the headlines. Not only does it bring the number of pyramids discovered in Egypt to 118, but it enriches our knowledge of the Sixth Dynasty and its royal family members. Sesheshet's pyramid, found seven metres beneath the sands of the Saqqara necropolis, is five metres in height, although originally it reached about 14 metres. The base is square and the sides of the pyramid slope at an angle of 51 degrees. The entire monument was originally cased in fine white limestone from Tura, of which some remnants were also unearthed. Ushabti (model servant) figurines dating from the third Intermediate Period were also found in the area, along with a New Kingdom chapel decorated with a scene of offerings being made to Osiris. Also found were a group of Late Period coffins, a wooden statue of the god Anubis, amulets, and a symbolic vessel in the shape of a cartouche containing the remains of a green substance. These objects will be transported to the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square where they will be restored and put on display. According to Zahi Hawass, secretary-general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), who led the excavation team, the finds show that the entire area of the Old Kingdom cemetery of Teti was reused from the New Kingdom through to the Roman Period. Culture Minister Farouk Hosni described it as "a great discovery" and said he wished that within the next couple of weeks excavators could find more of the funerary complex of the queen. "Sesheshet's pyramid is the third subsidiary pyramid to be discovered within Teti's cemetery," Hawass said. He added that earlier excavations at the site had revealed the pyramid of King Teti's two wives, Khuit and Iput. "This might be the most complete subsidiary pyramid ever found at Saqqara," he said. Scholars have long believed that Khuit was Teti's secondary wife, but excavations and studies proved that her pyramid was built before that of Queen Iput, who was previously believed to have been Teti's chief queen. The fact that her pyramid was built before Iput's, however, tells us that Khuit was in fact the primary royal wife. Previous excavations at this site have also revealed the funerary temple of Queen Khuit, offering much new information about the decorative codes of queens' monuments of the period. "No one can ever know what's hidden beneath the sands of Egypt," Hawass told Al-Ahram Weekly, adding that the excavators had been somewhat surprised to find a pyramid within Teti's cemetery since they thought the area had been thoroughly explored. In fact, he continued, over the last century, since French archaeologists Auguste Mariette found Teti's pyramid, archaeologists had used the area as a sand dump as they considered it empty and without anything of interest. Teti's pyramid is mostly a pile of rubble constantly threatened with being covered by sand. There is a steep pathway that leads to the burial chamber, where the walls are decorated with the pyramid texts and the ceiling decorated with stars. Inside the chamber was found an undecorated sarcophagus containing a mummified arm and a shoulder, presumably Teti's. Up to now no other parts of Teti's pyramid complex; the valley temple and causeway have been discovered. However, in addition to the subsidiary pyramids of the king's wives and mother, tombs of his consorts and viziers have been found. Among these are those of his chancellors Mereruka and Kagemni. The archaeologists found that a shaft had been created in Sesheshet's pyramid to allow access to her burial chamber, so they do not expect to find Sesheshet's mummy when they reach the burial chamber within the coming two weeks. However, they anticipate finding inscriptions about the queen, whose name, according to Hawass, was only known from being mentioned in a medical papyrus containing a recipe, supposedly created to her request, to strengthen the hair. It is also believed that Queen Sesheshet was instrumental in enabling her son to gain the throne and reconciling two warring factions of the royal family. The dynasty that arose with her son is considered part of the Old Kingdom portion of the history of Egypt, a term designated by modern historians. There was no break in the royal lines or the location of the capital from its predecessors, but significant cultural advances occurred to prompt the designation of different periods by scholars. Until the recent rediscovery of her pyramid, little contemporary evidence about her had been found. Her estates under the title King's Mother are mentioned in the tomb of the early Sixth-Dynasty vizier Mehu, and she is referenced in passing as the mother of King Teti in the remedy for baldness in the Ebers Papyrus. After the death of Unas, the last king of the Fifth Dynasty, Teti took the throne. The exact length of his reign is not known as it was destroyed in the Turin Kings' List, but the last year that can be attributed to his reign was the year of the sixth cattle count, which means roughly 11 years. Many of the officials and administrators from the reign of Unas remained during the rule of Teti, who seemed intent on restabilising the central government. So far nothing is shown about his military campaigns or trade agreements, but it is assumed that diplomatic relations between north and south continued in the customary way. He quarried in the south and imported timber for building from Syria. Teti granted land to Abydos by decree, and he was also the first known king with links to the cult of the goddess Hathor in Dendereh. Reliefs found at Abydos show that he exempted the area from taxes, probably because of a bad harvest or inundation. During Teti's reign high officials were beginning to build funerary monuments that rivalled that of the king. For example, his chancellor Mereruka built a large mastaba consisting of 32 rooms, all richly carved. This is considered a sign that wealth was being transferred from the central court to the officials, a slow process that culminated in the end to the Old Kingdom. Teti may have been murdered by the usurper Userkare; the historian Manetho states that he was murdered by his palace bodyguards in a harem plot. Source : http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2008/923/he1.htm

|

|

Long-isolated Libya plans new archaeology drive (Lybia) 18 November 2008 TRIPOLI (Reuters) - Libya plans to invite the world's top archaeologists to unearth its ancient past as it tries to lure more tourists after decades in isolation, the head of the government's archaeology department said. With a central role in early human migration, the desert country on the Mediterranean is home to a multitude of ancient and prehistoric sites. Many are thought to remain undiscovered. But years of western sanctions tarnished Libya's image and only a few hundred thousand people visit the north African country each year, compared to over 8 million for neighbouring Egypt. "We will open our arms to the best scientists from Japan to the United States. We will not exclude one major institution, be it Oxford, Cambridge, the Sorbonne or Rome," said Giuma Anag, chairman of the government's archaeology department. In a recent interview, he described discoveries to date as only the tip of the iceberg. The archaeology campaign is backed by leader Muammar Gaddafi's most prominent son, Saif al-Islam, who recently approved setting up of a society for safeguarding archaeology that would coordinate the work of foreign and local researchers. "It is a huge acceleration," Anag told Reuters. "We never had this kind of support before." Archaeology took a back seat after Gaddafi's 1969 Islamic Socialist revolution although work never entirely stopped. Some foreign archaeologists continued work -- making significant finds -- even during the low point of relations with the West. Libya, three times the size of France, was inhabited by humans over 60,000 years ago when Homo Sapiens began moving north from east Africa before colonizing Europe. In ancient times, coastal settlements were established by great civilisations from the Phonecians to the Romans, Greeks, Carthaginians and Ottomans. Archaeological work began in earnest in the 1930s when Italian fascist colonialists hoped to demonstrate the Roman presence and prove Italy's historical dominance of the Mediterranean. That work also led to the discovery of oil. 150,000 YEARS With a low population and dry climate, Libya's secrets are well preserved. Historians say the vast desert was once savannah that supported small communities of which little is known. "We are discovering more about one of the most interesting aspects of human pre-history -- when and how Homo Sapiens left Africa," said Elena Garcea of Cassino University in Italy. With new technology for dating objects, her team has found evidence of human habitation in Libya up to 150,000 years ago and is unearthing details of little-known Early-Middle Stone Age societies. Key discoveries were made in recent years by French researcher Andre Laronde at the ancient Greek port of Apollonia in Cyrenaica, birthplace of the philosopher and mathematician Erastosthenes. In the south, an Italian team has studied rock art to shed light on prehistoric hunter-gatherer communities. A Sicilian group is working on the wreck of a 17th century Venetian warship, the Tigre, scuppered by its captain after a storm drove it south and the Libyan Karamanli fleet gave chase. The team's head, Sebastiano Tusa, says the ship is yielding useful information on the period when Venice's power waned and Turkish forces threatened its eastern Mediterranean possessions. But Tusa's dream is to find a land settlement on the Libyan coast that proves there was a sea route via North Africa for ships travelling between the Western and Eastern Mediterranean in the second millennium B.C. "I'm sure there will be something proving a connection between Crete and the Aegean and Cyrenaica," he said. Libya's government says that as more sites are opened up, it wants to avoid the mass tourism of Egypt and Tunisia and its emphasis on history will help draw a smaller number of discerning travellers. "We will discourage mass tourism which would ... be a disgrace towards this fantastically rich and diverse cultural heritage," said Anag. Source : http://africa.reuters.com/top/news/usnJOE4AH0GQ.html

| |

|

Ancient Egypt had powerful Sudan rival, British Museum dig shows (Sudan) 16 October 2008 New evidence about the power of a Sudanese civilisation that once dominated ancient Egypt has come to light thanks to a British Museum expedition. The Second Kushite Kingdom controlled the whole Nile valley from Khartoum to the Mediterranean from 720BC to 660BC. Now archaeologists have discovered that a region of northern Sudan once considered a forgotten backwater once actually "a real power-base". They discovered a ruined pyramid containing fine gold jewellery dating from about 700BC on a remote un-navigable 100-mile stretch of the Nile known as the Fourth Cataract, plus pottery from as far away as Turkey. Other finds included numerous examples of ancient rock art and 'musical' rocks that were tapped to create a melodic sound. They only made the discoveries after being invited by the Sudanese authorities to help excavate part of the Merowe region, which is soon to be flooded by a large hydro-electric dam. More than 10,000 sites were found. Historians had written off the area as being of little archaeological interest. Dr Derek Welsby, of the British Museum, said: "We had no idea how rich the area was." Remarkably well-preserved bodies, naturally mummified in the desert air, and a cow buried complete with eye ointment were also unearthed. Dr Welsby said the finds revolutionised the history and geography of the Kushite kingdoms. The First Kushite Kingdom rivalled Egypt for power between 2500BC and 1500BC, when many of Egypt's largest pyramids were built, he said. "All our preconceptions about this being a relatively poor, inhospitable area were completely wrong," he remarked. We thought the first kingdom gradually grew over 1,000 years; now we know it happened right at the beginning, very rapidly. "During the second kingdom we thought it was an area everybody bypassed. But finding the pyramid meant it was a real power-base. This was not a backwater, it was partaking in the major trade routes in the world." The team was able to excavate hundreds of heavy items, including large blocks adorned with rock art and 390 stones that comprised the pyramid, with the help of trucks and cranes lent by Iveco and New Holland. The Sudanese authorities gave 20 such blocks and musical 'rock gongs', plus pottery and jewellery to the British Museum. A selection will be put on display early next year. Source : http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/sudan/3209644/ Ancient-Egypt-had-powerful-Sudan-rival-British-Museum-dig-shows.html

| |

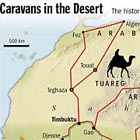

A generalised map of the Sahara shows the location of the sample sites and the fossilised river courses (Credit: Univeristy of Bristol) |

Did ancient river channels guide humans out of Africa ? (Africa) 14 October 2008 The first humans to leave Africa didn't have to struggle over baking sand dunes to find a way out - instead they might have followed a now-buried network of ancient rivers, researchers say. Chemical analysis of snail fossils suggests that monsoon-fed canals criss-crossed what is now the Sahara desert as modern humans first trekked out of Africa. Now only visible with satellite radar (see an image), the channels flowed intermittently from present-day Libya and Chad to the Mediterranean Sea, says Anne Osborne, a geochemist at the University of Bristol, UK, who led the new study. Up to five kilometres wide, the channels would have provided a lush route from East Africa - where modern humans first evolved - to the Middle East, a likely second stop on Homo sapiens' world tour. Archaeological, genetic and palaeontological evidence have pointed to the Nile River Valley and Red Sea as other potential alleys for human migration out of Africa. Watery clues To make a case for the channels, Osborne's team excavated snail fossils buried by half a metre of sand from a channel in Libya and compared their chemical makeup to rocks from volcanoes hundreds of kilometres away. By measuring the decay of a radioactive metal locked into the shells and rocks, Osborne's team showed that the buried snails must have incorporated water that flowed from the volcanoes. Other climate records point to a sometimes-green Sahara around this time, and Osborne thinks that seasonal monsoons could have supported a patchwork of life-saving oases across the desert. Chris Stringer, a palaeoanthropologist at London's Natural History Museum, says Osborne's team makes a good climatological case for the importance of the Saharan channels in human migrations. North African human bones and artefacts closely match those in the Middle East, but, he says, a greener Sahara could have connected already existing populations in both spots to achieve the same effect. Better proof could come with archaeological finds documenting a human migration across the Sahara, he says. Yet it's a task that few researchers have taken on so far. "It's up to the archaeologists now to go and have a search," Osborne says. Source : http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn14935-did-ancient-river-channels-guide-humans-out-of-africa.html

|

Recovered treasures include copper ingots, ivory and cannons.  Copper ingots carry a trident seal used by the Fugger family  Portuguese gold coins are part of the recovered cargo |

Uncovering Namibia's sunken treasure (Namibia) 26 September 2008 By Frauke Jensen - BBC News, Oranjemund, Namibia A team of international archaeologists is working round the clock to rescue the wreck of what is thought to be a 16th Century Portuguese trading ship that lay undisturbed for hundreds of years off Namibia's Atlantic coast. The shipwreck, uncovered in an area drained for diamond mining, has revealed a cargo of metal cannonballs, chunks of wooden hull, imprints of swords, copper ingots and elephant tusks. It was found in April when a crane driver from the diamond mining company Namdeb spotted some coins. The project manager of the rescue excavation, Webber Ndoro, described the find as the "the most exciting archaeological discovery on the African continent in the past 100 years". "This is perhaps the largest find in terms of artefacts from a shipwreck in this part of the world," he said. Skeleton coast The ship may have been unable to withstand the currents in the volatile seas off the Namibian shore. The area is also known as the Skeleton Coast and is associated with the skeletons of wrecked ships and past stories of sailors wandering through the barren landscape in search of food and water. Working out whose ship this was is no easy task. Gold coins that the Portuguese crown began producing in October 1525 mean it could not have been the vessel of the famous seafarer Bartholomew Dias, who disappeared on one of his travels around the point of Africa in the year 1500. But there are other pointers, including swivel-guns known to have been used by Portuguese and Spanish seafarers, and the boat's shape, indicating that it was a Portuguese "nau". There are also copper ingots carrying a clearly visible trident seal that can be traced back to the German banker and merchant family of Jakob Fugger - the main suppliers of primary materials to the Portuguese crown. Gold and silver coins have been deposited in a bank vault. Rare navigational instruments have been sent to Portugal for research, while pewter plates and jugs, pieces of ceramic, tin blocks and elephant tusks are temporarily housed in a warehouse on the premises of the mining company. Some are being freed of their layer of sand and salt to allow for more detailed scrutiny over their make and origin. "It represents a very interesting cargo - we have goods from Asia, we have goods from Europe, we have goods from Africa," said Mr Ndoro. "We always think that globalisation started yesterday but in actual fact here we are with something we can date to around 1500." Protected The site is about 130km (80 miles) south of the Namibian harbour town Luderitz, in an area long sealed off for mining. The mines are established by sea-walling the ocean and dredging the dry seabed for diamonds. Pumps ensure the sea does not reclaim the land - an exercise that is costing thousands of dollars each week. Bruno Werz, the archaeologist leading the excavations, said the shipwreck was particularly valuable because it had not been tampered with. "This collection has not been disturbed by human interference," he said. "We are very fortunate to have found an untouched wreck with all the material that was on site still here in one collection." Archaeologists from South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, the United States, the UK and Portugal are working on the excavation, which is due to be completed by mid-October. Thereafter the detailed work of recording and preserving, which can take up to 30 years, can begin. Stone and metal cannonballs and other artefacts are being covered with plastic and sand to protect them from sun and air. Mr Ndoro said the shipwreck was a very important find for Africa. "Here we have different African countries cooperating to make sure we have saved this ship and we have something we can show to the world." "I am sure there will be many more wrecks to be found here," he added. "Namibia should invest in training archaeologists." Source : http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7634479.stm

|

|

Namibian Portuguese shipwreck hailed as one of the best (Namibia) 23 September 2008 ORANJEMUND: A treasure-laden 16th-century Portuguese vessel that ran aground off Namibia's coast was hailed by archaeologists yesterday as providing a rare insight into the heyday of seafaring explorations between Europe and the Orient. "This is a cultural treasure of immense importance," Bruno Werz said when offering journalists a first glimpse of the precious find at the excavation site in Namibia's diamond-rich "sperrgebiet" or no-go zone. The shipwreck, which was discovered by geologists dredging for diamonds in April, is the oldest found in sub-Saharan Africa. Werz's team of scientists are from Namibia, the US, Portugal, South Africa and Zimbabwe. It was thought that the ship was linked to Bartholomew Diaz, the first European to round the Cape of Good Hope, in 1488, but some of the ship's 2 000 gold coins were dated October 1525, 25 years after Diaz disappeared. A Portuguese archaeologist described it as the best-preserved example of Portuguese seafaring outside Portugal. With diamond mining company Namdeb spending vast amounts to keep the sea at bay while the excavations take place, pressure is on the team to finish the work by early next month. - Sapa-dpa Source : http://www.themercury.co.za/index.php?fArticleId=4624653

| |

The obelisk was surrounded by scaffolding for reassembly |

Ethiopia unveils ancient obelisk (Ethiopia) 4 September 2008 Ethiopia is celebrating the unveiling of the reassembled Axum obelisk, one of the country's greatest treasures. The obelisk, at least 1,700 years old, was looted by Italian troops in the 1930s and returned to Ethiopia in 2005. A giant Ethiopian flag was removed from the obelisk in front of what organisers said was a crowd of tens of thousands in the ancient northern town of Axum. The ceremony is the last big event of Ethiopia's millennium year, the year 2000 by the country's Coptic calendar. The president and prime minister were among the officials attending. Ancient empire Intricately carved obelisks were erected at the tombs of Ethiopia's ancient kings when Axum was the centre of a great empire. But only one remained standing amid the tumbled blocks of its former companions, the BBC's Elizabeth Blunt reports from Ethiopia. The Axum obelisk was taken by troops in 1937 during the Italian occupation. The monument weighs more than 150 tonnes and was brought back from Italy in three pieces. Its return followed decades of negotiations between the Italian and Ethiopian governments, and long delays in transporting the heavy stones from Rome. The monument has now been restored and resurrected in its original home. It had been lying on the ground for centuries when the Italians found it, and some archaeologists argued it should have been replaced in that position to avoid damage to it or nearby networks of underground tombs. But others have said Ethiopians should be able to see the obelisk in its original position. Ethiopia's ambassador to the UK, Berhanu Kebede, told the BBC's Network Africa programme that the obelisk would help his country "to build a stronger and vibrant nation". "We have fought a protracted battle to bring back our historical asset, and this is very important because it's a manifestation of who we are and it also shows what our ancestors have done," he said. "The obelisk shows the architectural talent of our ancestors and modern architects are fascinated how the Ethiopians were able to do that during that period." Source : http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7597589.stm

|

AFP/MPFT/File Photo: Undated handout photo shows the 3D reconstruction of the skull of Toumai. |

Finder of key hominid fossil disputes 7-million-year dating (Chad) 1 September 2008 PARIS (AFP) - A fresh storm has broken out over an ancient fossil presented by its defenders as a forebear of humanity and dismissed by its critics as the remains of a vulgar chimp. Controversy has swirled around Toumai, the name given to the nearly-complete skull, ever since it was found in the Chadian desert in 2001. Toumai's big defender is French palaeontologist Michel Brunet, a professor at the prestigious College de France, who says Toumai walked the Earth shortly after chimpanzees and hominids diverged from a common ancestral primate. Brunet has been roundly attacked in other quarters. Critics are incensed that he has given a hominid honorific (Sahelanthropus tchadensis) to a creature whose cranium, in their view, was too squashed to be that of a pre-cursor of Homo sapiens. They calculate that Toumai's height was no more than 120 centimetres (four feet) -- or that of an adult chimpanzee. Brunet appeared to have scored a knockout blow in February this year, when radiological measurements estimated that the soil where Toumai was found was between 6.8 million and 7.2 million years old. The study appeared in a top-line US journal, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. But the man who discovered Toumai, Alain Beauvilain, of the University of Paris at Nanterre, has now publicly challenged this estimate. Beauvilain declined to take part in the hominid-vs.-chimp debate, but said he questioned the dating's methods and the way it had been presented to the public. "It's time to set the record straight," he told AFP. In general, radiodating of the sediment in which a fossil is found is considered to be a good guide to when the creature died, its remains eventually becoming covered by soil or other debris. But Beauvilain, a Chadian fossil expert of long standing, says that, contrary to Brunet's assertions that the fossil had been "unearthed," the cranium was found loose on the sand. A thick blue ferruginous, or iron-based, mineral encrusted the skull, which showed clear signs of weathering from desert conditions, Beauvilain says in a commentary in the South African Journal of Science. Beauvilain says it is clear that the soil around the find, and possibly the find itself, had been shifted by wind or erosion, a phenomenon that can happen swiftly and frequently in the desert. So carbon-dating the soil and attributing that to the skull was a perilous exercise, he says. "How many times was it exposed and reburied by shifting sands before being picked up?" he asks in the commentary. Beauvilain also takes issue with the soil samples used for the PNAS study and analysed by experts from France's National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). He says these samples were taken selectively and did not give a full picture of the depth and range of topography in which the find was made. He describes some of the collection choices as "astonishing." On the same grounds, Beauvilain attacks Brunet's dating of an ancient Chadian jawbone, dubbed Abel and estimated to be between three million and 3.5 million years old. "Abel," too was picked up on the surface in 1995, and was not embedded in the soil, he says, showing photos of both finds on their day of discovery. The debate is important because of its implications for anthropology. Toumai -- the name means "hope of life" in the local Goran language -- was found 2,500 kilometers (1,500 miles) west of the Great Rift Valley, until now considered the cradle of humanity. So if the skull's dating is right, it implies the early hominids ranged far wider from East Africa, and far earlier, than previously thought. The discovery also implies hominids evolved quickly from apes after they split from a common primate ancestry. Hominids are considered the forerunners of anatomically modern humans, who appeared on the scene about 200,000 years ago. Still unclear, though, is the exact line of genealogy from these small, rather ape-like creatures to the rise of the powerfully-brained Homo sapiens. Source : http://news.yahoo.com/s/afp/20080901/sc_afp/sciencefrancechadpalaeontology_080901235847;_ylt=AtuQ4SAUN3kbuGa8u_t5M31FeQoB

|

|

Earliest Known Human Had Neanderthal Qualities (Ethiopia) 22 August 2008 The world's first known modern human was a tall, thin individual -- probably male -- who lived around 200,000 years ago and resembled present-day Ethiopians, save for one important difference: He retained a few primitive characteristics associated with Neanderthals, according to a series of forthcoming studies conducted by multiple international research teams. The extraordinary findings, which will soon be outlined in a special issue of the Journal of Human Evolution devoted to the first known Homo sapiens, also reveal information about the material culture of the first known people, their surroundings, possible lifestyle and, perhaps most startling, their probable neighbors -- Homo erectus. "Omo I," as the researchers refer to the find, would probably have been considered healthy-looking and handsome by today's standards, despite the touch of Neanderthal. "From the size of the preserved bones, we estimated that Omo I was tall and slender, most likely around 5'10" tall and about 155 pounds," University of New Mexico anthropologist Osbjorn Pearson, who co-authored at least two of the new papers, told Discovery News. Pearson said another, later fossil was also recently found. It too belonged to a "moderately tall -- around 5'9" -- and slender individual." "Taken together, the remains show that these early modern humans were...much like the people in southern Ethiopia and the southern Sudan today," Pearson said. Building On Leakey's Work Parts of the Omo I skeleton were first excavated in 1967 by a team from the Kenya National Museums under the direction of Richard Leakey, who wrote a forward that will appear in the upcoming journal. Leakey and his colleagues unearthed two other skeletons, one of which has received little attention. Two of the three skeletons found at the site have been a literal bone of contention among scientists over the past four decades. Reliable dating techniques for such early periods did not exist in the late 60's, and the researchers could not agree upon the identity of the two skeletons. From 1999 to the present, at least two other major expeditions to the southern Ethiopian site -- called the Kibish Formation -- have taken place, with the goal of solving the mysteries and learning more about what the area was like 200,000 years ago. As evidenced by photographs showing the researchers followed by armed guards, work at this location proved challenging. "It took us five plus days to get there from Addis," paleobiologist Josh Trapani of the Smithsonian Institution and the University of Michigan told Discovery News. "Once there, we had intense heat, hyenas outside camp, crocodiles in the river, many insects and two remarkable and very different groups of people, the Mursi and the Nyangatom on opposite sides of the river who were our partners in some of this work." Primitive, Yet Still Like Us The ordeals proved successful, as the scientists have recovered new bones for Omo I, some of which perfectly fit into place with the remains Leakey unearthed over 40 years ago. Several scientists analyzed the bones, including a very detailed, comparative look at the shoulder bone by French paleontologist Jean-Luc Voisin. They concluded that, without a doubt, Omo I represents an anatomically modern human, with bones in the arms, hands and ankles somewhat resembling those of other, earlier human-like species. "Most of the anatomical features of Omo are like modern humans. Only a few features are similar to more primitive hominids, including Neanderthals and Homo erectus," explained John Fleagle, distinguished professor in the Department of Anatomical Sciences at Stony Brook University in New York. "Omo II is more primitive in its cranial anatomy," he added, "and shares more features with Homo erectus and fewer with modern humans." Unlikely Neighbors New dating of the finds determined that Omo II lived at around the same time and location as Omo I, indicating that Homo sapiens may have coexisted with Homo erectus, a.k.a. "Upright Man," who is believed to have been the first hominid to leave Africa. Fleagle explained the detailed nature of the latest dating techniques that place both skeletons at around the 200,000-year-old period. He said both skeletons were recovered from rocky geological layers, with "Adam" unearthed just above a layer of volcanic rock. Precise dates can then be calculated because "when volcanic rocks form, they start a radiometric clock that ticks at a regular rate." Fleagle added, "By looking at the ratio of parent minerals and daughter minerals you can calculate when the rocks were initially formed." Source : http://dsc.discovery.com/news/2008/08/22/earliest-human-ethiopia.html

| |

|

Tanzania: Prehistoric Weapons Factory (Tanzania) 3 August 2008 THE ISIMILA STONE AGE SITE in Tanzania provides fascinating insights into how ancient man developed the tools to master his environment. Stone tools and artefacts found at Isimila near Iringa town, over 500 kilometres from Dar es Salaam, show that the Hehe -- one of the ethnic groups in the region -- used the site as a sort of Stone Age weapons factory. Excarvation in Iringa region, especially Mtera and Upper Kihansi, indicate that there were settlements in these areas from as early as 200,000 years ago to as late as the Iron Age. According to Mohammed Ngoma, a conservationist at the Isimila Stone Age Site, Upper Kihansi too was a production site for stone tools of the Neolithic period, which include pot shards and remains of iron works. The Iron Age settlements in Iringa district and rock paintings at Kombangulu in Kilolo district also provide fascinating glimpses into the lives of early humans. The Isimila site is reputed to have been inhabited from 300,000 to 400,000 years ago. The soil erosion that has been occurring there over the millennia, has uncovered remains of stone tools, animals and plants that have contributed to the understanding of the pre-history of the area. The stone tools currently preserved at Isimila include knives, slingshots, stone hammers, hand axes, scrapers, and spears. A magnificent "Mgoha" spear on display at the site, for instance -- made in the year 1700 by the Hehe ethnic group -- was donated to the site by one Zuberi Mwamwitala. SUCH TOOLS AND WEAPONS served to protect the people from enemies -- both human and animals as well as to hunt animals for food. The Isimila site was discovered in 1951 by D.A McCleman of Saint Peters School in Johannesburg. On his way from Nairobi to Johannesburg, he collected some stone tools from the site and deposited them with the Archaeological Survey Union of South Africa. The first excavation works at the site were done from July to November 1957, followed by another excavation from July to August 1958. During these two excavations, a detailed geological survey of Isimila was carried out and Dr Louis Leakey became the first researcher to examine the fauna remains recovered from the two excavations. The Isimila Stone Age Site is one of the richest exposures of Stone Age tools in Africa. According to Mr Ngoma, Stone Age implements found at the site are called Acheulian type because they are similar to implements found at St Acheal in France. Similar implements, which are estimated to be as much as half a million years old have also been found at Olduvai Gorge. The Acheulian tradition worldwide is known to date from about 1.5 million years ago. Erosion at Isimila has exposed many layers of soil and rocks of different types, marking the different historical periods. The tools are made from a variety of rocks such as granite and quartzite. Fossils found in the area suggest the existence of animals such as elephants, a variety of extinct pigs, giraffe and hippo. ARCHAELOGICAL RECORDS from Iringa indicate that the area had contact with the outside world by the 15th century. The ultimate control of the areas by outsiders started with the onset of Germany as a colonial power in 1891. The Germans arrived in Tanganyika in 1885 and established their capital in Bagamoyo district, some 45 kilometres from Dar es Salaam. From there, they started to consolidate their rule along the coast. This colonial venture ignited resistance by the people of the Coast. People like Abushiri (in 1888 to 1889) and Bwanaheri (from 1889 to 1894) resisted the German invasion. In Uhehe, now Iringa, German troops arrived in 1891. When Chief Mkwawa of the Hehe was informed of this, he immediately sent his solders to Lugalo to prevent them from approaching his capital at Kalenga. In August 17, 1891, Mkwawa's solders ambushed the Germans at Lugalo. The Germans were defeated and their leader, Zelewinsky, was killed. The name Lugalo was later used by the Tanzania Peoples' Defence Forces for one of its biggest barracks. Zelewinsky's pyramid shaped tomb, where he was buried along with a number of his solders, is still to be seen at Lugalo, a few metres from the Tanzania-Zambia highway. The Germans sent troops again in 1894 under new leadership. Mkwawa continued with his resistance for several years until he shot himself in 1898 to avoid being captured by the Germans. After the First World War, the Germans were defeated and their colonies placed under British authority. On independence in 1961, Adam Sapi Mkwawa, the grandson of Chief Mkwawa, became the first African Speaker of the Tanzanian National Parliament. Source : http://allafrica.com/stories/200808190350.html

| |

SAHARAN BURIAL - The skeletons of a woman and two children are the first triple burial uncovered in Africa, researchers say. Preserved in this cast exactly as found, the skeletons were part of the oldest Stone Age graveyard in the Sahara |

Saharan surprise : A Stone Age graveyard offers insights into two poorly understood cultures (Niger) 14 August 2008 Investigators searching for dinosaur fossils in the Sahara in 2000 suddenly took an unexpected and scientifically exciting leap backward in time. They came upon a stretch of sand littered with the bones of ancient people positioned in ways characteristic of intentional burials. Investigations of the bones and associated finds made since that fateful discovery show that they come from the largest and oldest Stone Age graveyard in the Sahara, team members report online in the Aug. 14 PLoS ONE. They also described their findings August 14 during a press briefing held at the National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C., which partly funded the excavations. The Gobero archaeological site, which dates to as early as 10,000 years ago, lies in the western African nation of Niger. The area had already gained fame earlier when excavation director and paleontologist Paul Sereno of the University of Chicago found 110-million-year-old dinosaur fossils nearby. Work at Gobero indicates that two successive human populations divided by 1,000 years lived by a lake, perhaps seasonally, during a time of regular Saharan rainfall. These hunter-gatherer groups buried their dead in separate gravesites by the lake, leaving an unprecedented biological and material record of their poorly understood cultures. Although hunter-gatherer groups are typically mobile and small in number, those living in resource-rich areas tend to stay for long periods at seasonal sites, comments anthropologist Henry Harpending of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. “It’s interesting that at Gobero these ancient populations became dense enough to require large cemeteries,” he says. Excavation seasons in 2005 and 2006 have revealed 200 graves. Human and animal bones, as well as bone artifacts, have yielded 78 radiocarbon dates, which are based on ratios of different isotopes of carbon in the bones and artifacts. “I’ve never seen an archaeological site that’s as exceptional as Gobero is,” archaeologist and team member Elena Garcea of the University of Cassino in Italy said at the press briefing. The older Gobero group, members of the Kiffian culture, hunted large game and speared two-meter-long perch with bone harpoons. They colonized the Sahara from 10,000 to 8,000 years ago, when heavy rains created a deep lake at Gobero. Pottery pieces at the site are decorated with zigzags and wavy lines already linked to the Kiffians, Garcea says. Kiffians buried dead individuals with their legs pulled up tightly against their body, suggesting that the deceased were bound up with some type of wrapping. Both adult males and females often reached two meters in height. The later Gobero residents, from the Tenerian culture, hunted small game using tiny stone arrowheads, caught small catfish and tilapia and herded cattle. The Tenerians inhabited the site from 7,200 to 4,200 years ago, when it featured a shallow lake. Parallel lines of impressed dots cover Tenerian pottery. Tenerians were shorter and had slighter builds than Kiffians did. Tenerians often buried their dead with jewelry and placed them in ritual poses. The 4,800-year-old skeleton of a girl lying on her side, with arms and legs slightly bent, includes an upper-arm bracelet carved from a hippo’s tusk. Based on her bone development, the researchers estimate that the girl was 11 years old when she died. The most striking find occurred in 2006, when the researchers uncovered what they say is Africa’s first triple burial. A petite, 40-year-old Tenerian woman lay on her side, facing two children, an 8-year-old and a 5-year-old. Their entwined arms reached out and their hands clasped in what Sereno’s team calls the “Stone Age embrace.” These individuals died from undetermined causes 5,300 years ago. Source : http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/35314/title/Saharan_surprise

|

The boat is entirely wooden and has only one sail  The vessel was designed from archaeological evidence  Local boatmakers said they had never done anything like it before |

Around Africa in a Phoenician boat 9 August 2008 On Arwad Island off the coast of Syria, a group of 20 sailors-to-be are preparing for a voyage their captain believes has not been undertaken for two and a half millennia. They plan to set off on Sunday on a journey that attempts to replicate what the Greek historian Herodotus mentions as the first circumnavigation of Africa in about 600BC. Their vessel, the small, pine-wood Phoenicia, is modelled on the type of ship the Phoenician sailors he credited with the landmark voyage would have used. The Phoenicians lived in areas of modern-day Lebanon, Syria and other parts of the Mediterranean from about 1200BC and are widely credited with being both strong seafarers and the first civilisation to make extensive use of an alphabet. Mammoth project Celebrating Damascus as a capital of Arab Culture for the year 2008, event organisers sponsored the British-run expedition project to mark their festivities. The year-long voyage will take the crew into some of the most dangerous waters in the world. As well as sailing round the southern most tip of Africa, they are preparing to deal with pirates and long periods of waiting for favourable winds. The skilful shipbuilders in Arwad are familiar with construction techniques dating back 200-300 years, but shipbuilder Orwa Bader, 28, says this is the first time they have ever tried to build in the Phoenician style. "Usually it takes three men and two months to build any type of ship. But this time, we needed at least five to 10 builders to work on it over eight months to make it ready. It was a hard but enjoyable job." The vessel, designed on the basis of information from wrecked ships, pottery and other archaeological artefacts from the era, is made entirely of wood, with a single sail and no engine. The only concession to 21st Century sailing equipment is its navigational system. Its top speed will be the equivalent of 10km/h on land. Piracy fears The route goes through the Red Sea, past Somalia and down the East African cost before rounding the southern tip of Africa around Christmas time. The ship's skipper, Philip Beale, planned the voyage. "The most difficult part will be circumnavigating around the Cape of Good Hope where many shipwrecks are testimony to the difficult conditions there. You can get big waves of 20 metres or more there. It is a dangerous area and we'll be there in December and January." He predicts they have a 70% chance of completing the voyage successfully. "But there's a 30% chance we make a serious navigational error or we come up against pirates and we are kidnapped or something," he adds. Few luxuries The ship will be crewed by a largely British team of volunteers, some of whom have never done anything similar. Living conditions will be tough, and little different from those the Phoenicians would have endured. The experience will be new for John Bainbridge, 23: "It's about how you get on with people. That's the most essential skill," he says. And Julia Rouc, 26, originally from Zimbabwe, is hoping to spend time reading and possibly continue developing her aspirations to become a professional artist. "I am excited about it. It is a great experience. I am used to living in tough conditions so it is all fine by me. But I am not sure if I will have time to continue painting." Below deck, it feels extremely hot. There will be no ventilation and no running water, and one toilet for the 20 crew members. Their bunks are barely big enough to lie in. Unlike the Phoenicians' ships, the vessel will be equipped with lifeboats, and will carry large amounts of food and fresh water. But just like the ancient sailors, the crew will not really know how the boat will fare until it hits the open sea. Source : http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/7550162.stm

|

|