> ARI : News on the Net : news on world archaeology (Audio, Blogs, Text, Video).

> Daily archaeology news from the Internet (on www.archaeologica.org).

> Latest publications : North Africa, Sahara, West Africa - in french

> Latest publications : Central Africa - in french

> African-archaeology.net news archives : 2012 - 2011 - 2010 - 2008 - 2007 - 2006 -

2012 NEWS CONTENTS:

=> Early Human Ancestors May Have Walked AND Climbed for a Living (Africa) 31 December 2012

=> Scientists Research First Stone Tool Industries in Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania) 22 December 2012

=> Scientists 'Surprised' to Discover Very Early Ancestors Survived On Tropical Plants,

New Study Suggests (Africa) 14 December 2012

=> Tracing humanity's African ancestry may mean rewriting 'out of Africa' dates (Africa)

13 December 2012

=> The First Modern Humans Arose in South Africa, Say Researchers (South Africa) 5 December 2012

=> Sorry, vegans: Eating meat and cooking food made us human (Africa) 19 November 2012

=> Anthropologist finds large differences in gait of early human ancestors (Africa) 12 November 2012

=> Small lethal tools have big implications for early modern human complexity (South Africa)

7 November 2012

=> Human expansion from Africa comes into focus (Africa) 1 November 2012

=> New Stanford analysis provides fuller picture of human expansion from Africa (Africa) 22 October 2012

=> Study Suggests Early Humans Ate Meat 1.5 Million Years Ago (Tanzania, East Africa) 3 October 2012

=> Humans hunted for meat 2 million years ago (Tanzania, East Africa) 23 September 2012

=> Extensive DNA Study Sheds Light on Modern Human Origins (Africa) 20 September 2012

=> Studies slow the human DNA clock (Africa) 18 September 2012

=> DNA hints at African cousin to humans (Africa) 8 September 2012

=> Stone-Tipped Spears Used Much Earlier Than Thought, Say Researchers (South Africa)

8 September 2012

=> Malian treasures trapped in a culture war (Mali, West Africa) 25 August 2012

=> New Life for Nubian Bones (Egypt, North Africa) 20 August 2012

=> Climate and Drought Lessons from Ancient Egypt (Egypt, North Africa) 16 August 2012

=> Fossils point to a big family for human ancestors (Africa) 8 August 2012

=> Multiple Species of Early Homo Lived in Africa (Africa) 8 August 2012

=> Malindi archaeologists make new discoveries (Kenya, East Africa) 4 August 2012

=> A Modern Culture Emerged 44,000 Years Ago (South Africa) 30 July 2012

=> Modern culture emerged in Africa 20,000 years earlier than thought (South Africa) 30 July 2012

=> Sudan's Archaeological Sites Threatened by Proposed Dams (Sudan, East Africa) 22 July 2012

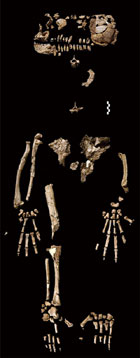

=> S.African scientists find most complete pre-human skeleton (South Africa) 12 July 2012

=> Timbuktu Arabs set up armed watch at ancient tombs (Mali, West Africa) 11 July 2012

=> Sudan relics at risk from dam floods. Appeal to archaeological community as proposals leave

three- to six-year window (Sudan, East Africa) 10 July 2012

=> DNA clues to Queen of Sheba tale (Ethiopia, East Africa) 21 June 2012

=> Ancient North Africans got milk. Herders began dairying around 7,000 years ago (Lybia, North Africa)

20 June 2012

=> Archaeological Site in Kenya Opening Window on Early Human Tool-Making (Kenya, East Africa)

13 June 2012

=> Thieves go on a treasure hunt in Egypt, taking advantage of country's turmoil (Egypt, North Africa)

13 May 2012

=> Ancient walking gets weirder: Fossils from two human ancestors suggest diversity in gait, stance

(Kenya, East Africa) 19 April 2012

=> Wadi Abu Subeira, Egypt: Palaeolithic rock art on the verge of destruction (Egypt, North Africa)

6 April 2012

=> Cutting through ancient evidence of human tool use (East Africa) 6 April 2012

=> Analytical standards needed for 'reading' Pliocene bones (East Africa) 5 April 2012

=> Scientists find evidence that human ancestors used fire one million years ago,

300,000 years earlier than believed (South Africa) 2 April 2012

=> First of Our Kind: Could Australopithecus sediba Be Our Long Lost Ancestor? (Africa, Southern Africa)

April 2012

=> 'Lucy' Lived Among Close Cousins: Discovery of Foot Fossil Confirms Two Human Ancestor Species

Co-Existed (Ethiopia, East Africa) 28 March 2012

=> Massive looting at El Hibeh, Egypt (Egypt, North Africa) 13 March 2012

=> Stone Age Pebble Holds Mysterious Meaning (South Africa) 23 February 2012

=> Making the bones speak (Sudan, East Africa) 22 February 2012

=> Out of Africa? Data fail to support language origin in Africa (Africa) 15 February 2012

=> Human evolution: Cultural roots (South Africa) 15 February 2012

=> Tunisia: Discovery of a Roman Cemetery in Djerba (North Africa, Tunisia) 14 February 2012

=> Ancient Farmers had Impact on Disappearance of African Rainforests (Central Africa) 9 February 2012

=> Czech archaeologists discover long-lost temple in Sudan (Sudan, East Africa) 27 January 2012

=> Arabia the First Stop for Modern Humans Out of Africa, Suggests New Study (Africa) 26 January 2012

=> Facebook in our Genes? (Southern Africa) 25 January 2012

=> Anthropology researcher searches for slave-era shipwreck (South Africa) 19 January 2012

=> River bank life of Early Humans (Ethiopia, East Africa) 15 January 2012

=> New Early Warning System Spotlights Endangered Archaeological and Cultural Heritage Sites

(Africa) 8 January 2012

=> Spreading a message of hope for Libyan archaeology (Lybia, North Africa) 7 January 2012

=> Look into the eyes of a rare ancient African sculpture (Nigeria, West Africa) 6 January 2012

A Twa hunter-gatherer in Uganda climbing a tree to gather honey. Credit: Nathaniel Dominy |

Early Human Ancestors May Have Walked AND Climbed for a Living (Africa) 31 December 2012 The results of recently conducted field studies on modern human groups in the Philippines and Africa are suggesting that humans, among the primates, are not so unique to walking upright as previously thought. The findings have implications for some of our earliest possible ancestors, including the 3.5+ million-year-old species Australopithecus afarensis, thought by many scientists to be the first known possible human predecessor to have forsaken arboreal life in the trees and live a life walking upright (bipedalism) on the ground. Associate professor of anthropology Nathaniel Dominy of Dartmouth College, along with colleagues Vivek Venkataraman and Thomas Kraft, compared African Twa hunter-gatherers to agriculturalists living nearby, the Bakiga, in Uganda. In the Philippines, they compared the Agta hunter-gatherers to the Manobo agriculturalists. They found that the Twa and the Agta hunter-gatherers regularly climbed trees to gather honey, an important element in their diets. More specifically, they observed that the climbers "walked" up small trees by applying the soles of their feet directly to the trunk and progressing upward, with arms and legs advancing alternately. To do this successfully, they said, required extreme dorsiflexion, or bending the foot upward toward the shin to a degree not normally possible among most modern humans. "We hypothesized that a soft-tissue mechanism might enable such extreme dorsiflexion," wrote the authors in their study report. They tested their hypothesis by conducting ultrasound imaging of the fibers of the large calf muscles of individuals in all four groups. The results showed that the Agta and Twa tree-climbers had significantly longer muscle fibers than those of their agricultural counterparts and other "industrialized" modern humans. "These results suggest that habitual climbing by Twa and Agta men changes the muscle architecture associated with ankle dorsiflexion," wrote the authors of the study. It demonstrated that a foot and ankle bone structure adapted primarily for walking upright on land does not necessarily exclude climbing as a behaviorally habitual means of mobility for survival. The implications for our possible early human ancestors, such as the species Australopithecus afarensis, are significant. "Australopithecus afarensis possessed a rigid ankle and an arched, nongrasping foot," wrote Dominy and his co-authors in the report published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). "These traits are widely interpreted as being functionally incompatible with climbing and thus definitive markers of terrestriality." But now, the research shows that bone structure alone is not an indisputable indicator that an ancient hominid was exclusively terrestrial. Australopithecus afarensis is an extinct hominid that lived between 3.9 and 2.9 million years ago. It was first discovered by Donald Johanson and colleagues in the Afar region of Ethiopia with the recovery of the partial skeleton of a 3.2 million-year-old specimen they named "Lucy". The find has represented a possible benchmark in human evolution for decades. Along with being among the earliest possible bipedal primates, it has also been thought to be closely related to the genus Homo (which includes the modern human species Homo sapiens), either as a direct ancestor or indirectly through an unknown earlier ancestor. Source : http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/december-2012/article/scientists-research-first-stone-tool-industries-in-olduvai-gorge

|

A chopping tool from Olduvai Gorge, 1 - 2 million years old. GFDL CC-BY-SA, Wikimedia Commons  A handaxe from Olduvai Gorge, over 1 million years old. This stone tool is most often associated with Homo erectus, a hominin considered by many scientists to be a possible human (Homo) ancestor. Homo erectus is widely thought to be the first species to venture out of Africa to populate the Middle East/Eurasia. British Museum, Discott, Wikimedia Commons |

Scientists Research First Stone Tool Industries in Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania) 22 December 2012 An international team of researchers have returned to Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania to unravel the mystery of how humans transitioned from the first stone tool technology to a more sophisticated industry. Olduvai Gorge, perhaps the most famous site for evidence of early humans, is again the subject of intense research on a decades-old question bearing on human origins: How, when and where did early humans evolve from using the first and simplest stone tool industry, that of Oldowan, to the second-oldest, and more sophisticated, stone tool technology known as the Acheulean? While Olduvai has been picked over before, most notably by the pioneering scientists L.S.B. and Mary Leakey, advances in archaeological investigative methods and the application of multidisciplinary approaches have made it possible to take another, more detailed and comprehensive look at both the old and the new among the world-famous exposed beds, the geological earthen layers or deposits that have historically produced some of the great ground-breaking discoveries related to early human evolution. Now, under the organizational umbrella of the Olduvai Geochronology Archaeology Project, an international team of scientists composed of a consortium of researchers and institutions is focusing on reconstructing the picture of the early human transition from the simple "chopper" stone tool technology of the Oldowan industry (see image below), the world's first technology discovered at Olduvai, to the Acheulean, the more sophisticated technology represented most by the well-known bifacial "handaxe" (see image below), some of the first examples of which were found at Saint- Acheul in France, and later at Olduvai. The Oldowan is considered to have been made and used during the Lower Paleolithic, from 2.6 to 1.7 million years ago, whereas the Acheulean emerged about 1.76 million years ago and was used by early humans up to about 300,000 years ago or later. To find answers, the team will be reappraising the chronological stratigraphy of Bed II, known to have yielded previous significant finds, and will be re-excavating some of the later beds of the best known fossil and stone tool sites. These beds reveal a record of a very important time period (1.79 - 1.15 million years ago), a record that contains evidence of critical changes in the area's fauna, stone tools and climate, such as the disappearance of Homo habilis, a very early hominin and possible human ancestor, and the emergence of Homo erectus, a later hominin considered to be the earliest human ancestor to exit Africa and spread across Eurasia. Scientists suggest that these same beds may include evidence of the long-sought transition from the more primitive Oldowan stone tools to the appearance of the more advanced Acheulean tools. Recent research at Olduvai has focused primarily on earlier beds, so research on these later beds will likely present new data to consider. Four key previously excavated sites will be investigated through full-scale excavation. More specifically, the team's objectives are including the following activities: - Conducting test pits (very limited, targeted excavations) at selective Bed II sites that have been determined to contain possible evidence related to the emergence of Acheulean tools at Olduvai; - Applying the new landscape sampling approach across Middle and Upper Bed II deposits and conducting random test pits in the various paleo-ecological settings; - Applying advanced dating methodologies to Bed II volcanic ashes to produce higher-resolution, more accurate dates for Bed II locations; - Measuring stratigraphic sections at and between key archaeological sites to determine their relative order and paleoecological contexts; - Determining the correlation of volcanic ash layers between sites to test previous proposed correlations and then establishing the basin-wide stratigraphic framework for Bed II; and finally, - Reconstructing the paleo-environments at Olduvai during the 1.7-1.3 Ma time period. Source : http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/december-2012/article/scientists-research-first-stone-tool-industries-in-olduvai-gorge

|

New research suggests that between three million and 3.5 million years ago, the diet of our very early ancestors in central Africa is likely to have consisted mainly of tropical grasses and sedges. (Credit: © timur1970 / Fotolia) |

Scientists 'Surprised' to Discover Very Early Ancestors Survived On Tropical Plants, New Study Suggests (Africa) 14 December 2012 New research by a University of Alberta archeologist may lead to a rethinking of how, when and from where our ancestors left Africa. Researchers involved in a new study led by Oxford University have found that between three million and 3.5 million years ago, the diet of our very early ancestors in central Africa is likely to have consisted mainly of tropical grasses and sedges. The findings are published in the early online edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. An international research team extracted information from the fossilised teeth of three Australopithecus bahrelghazali individuals -- the first early hominins excavated at two sites in Chad. Professor Julia Lee-Thorp from Oxford University with researchers from Chad, France and the US analysed the carbon isotope ratios in the teeth and found the signature of a diet rich in foods derived from C4 plants. Professor Lee-Thorp, a specialist in isotopic analyses of fossil tooth enamel, from the Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, said: "We found evidence suggesting that early hominins, in central Africa at least, ate a diet mainly composed of tropical grasses and sedges. No African great apes, including chimpanzees, eat this type of food despite the fact it grows in abundance in tropical and subtropical regions. The only notable exception is the savannah baboon which still forages for these types of plants today. We were surprised to discover that early hominins appear to have consumed more than even the baboons." The research paper suggests this discovery demonstrates how early hominins experienced a shift in their diet relatively early, at least in Central Africa. The finding is significant in signalling how early humans were able to survive in open landscapes with few trees, rather than sticking only to types of terrain containing many trees. This allowed them to move out of the earliest ancestral forests or denser woodlands, and occupy and exploit new environments much farther afield, says the study. The fossils of the three individuals, ranging between three million and 3.5 million years old, originate from two sites in the Djurab desert. Today this is a dry, hyper-arid environment near the ancient Bahr el Ghazal channel which links the southern and northern Lake Chad sub-basins. However, in their paper the authors observe that at the time when Australopithecus bahrelghazali roamed, the area would have had reeds and sedges growing around a network of shallow lakes, with floodplains and wooded grasslands beyond. Previously, it was widely believed that early human ancestors acquired tougher tooth enamel, large grinding teeth and powerful muscles so they could eat foods like hard nuts and seeds. This research finding suggests that the diet of early hominins diverged from that of the standard great ape at a much earlier stage. The authors argue that it is unlikely that the hominins would have eaten the leaves of the tropical grasses as they would have been too abrasive and tough to break down and digest. Instead, they suggest that these early hominins may have relied on the roots, corms and bulbs at the base of the plant. Professor Lee-Thorp said: "Based on our carbon isotope data we can't exclude the possibility that the hominins' diets may have included animals that in turn ate the tropical grasses. But as neither humans nor other primates have diets rich in animal food, and of course the hominins are not equipped as carnivores are with sharp teeth, we can assume that they ate the tropical grasses and the sedges directly." Source : http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/12/121214200916.htm

|

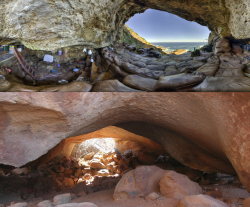

U of A anthropologist Willoughby believes that the items found prove continuous occupation of the areas over the last 200,000 years, through what is known as the "genetic bottleneck" period of the last ice age. Credit: John Ulan/ University of Alberta |

Tracing humanity's African ancestry may mean rewriting 'out of Africa' dates (Africa) 13 December 2012 New research by a University of Alberta archeologist may lead to a rethinking of how, when and from where our ancestors left Africa. U of A researcher and anthropology chair Pamela Willoughby's explorations in the Iringa region of southern Tanzania yielded fossils and other evidence that records the beginnings of our own species, Homo sapiens. Her research, recently published in the journal Quaternary International, may be key to answering questions about early human occupation and the migration out of Africa about 60,000 to 50,000 years ago, which led to modern humans colonizing the globe. From two sites, Mlambalasi and nearby Magubike, she and members of her team, the Iringa Region Archaeological Project, uncovered artifacts that outline continuous human occupation between modern times and at least 200,000 years ago, including during a late Ice Age period when a near extinction-level event, or "genetic bottleneck," likely occurred. Now, Willoughby and her team are working with people in the region to develop this area for ecotourism, to assist the region economically and create incentives to protect its archeological history. "Some of these sites have signs that people were using them starting around 300,000 years ago. In fact, they're still being used today," she said. "But the idea that you have such ancient human occupation preserved in some of these places is pretty remarkable." Magubike: Home to a modern Stone Age family? Willoughby says one of the fascinating things about Magubike is the presence of a large rock shelter with an intact overhanging roof. The excavations yielded unprecedented ancient artifacts and fossils from under this roof. Samples from the site date from the earliest stages of the middle Stone Age to the Iron Age. The earlier deposits include human teeth and artifacts such as animal bones, shells and thousands of flaked stone tools. The Iron Age finds can be dated using radiocarbon, but the older deposits must go through more specialized processes, such as electron spin resonance, to determine their age. Other parts of the Magubike rock shelter, excavated in 2006 and 2008, include occupations from after the middle Stone Age. Taken together, this information could be crucial to tracking the evolutionary development of the inhabitants. "What's important about the whole sequence is that we may have a continuous record of human occupation," said Willoughby. "If we do—and we can prove it through these special dating techniques—then we have a place people lived in over the bottleneck." Rugged, hilly terrain may have been key to survival The team made similar findings at Mlambalasi, about 20 kilometres from Magubike. Among the findings at this site was a fragmentary human skeleton that probably dates to the late Pleistocene Ice Age—after the out-of-Africa expansion but at the end of the bottleneck period. The bottleneck theory explains what geneticists have found by studying the mitochondrial DNA of living people—that all non-Africans are descended from one lineage of people who left Africa about 50,000 years ago. Reconstructions of past environments through pollen and other archeological records in Iringa suggest that people abandoned the lowland, tropical and coastal areas during that period but remained in the highlands, where vegetation has remained mostly unchanged over the last 50,000 years. Those who moved to higher ground may have found what is likely one of the few places that facilitated their survival and forced their adaptation. Further testing will determine whether these findings point to a clearer link to our African ancestors—a find Willoughby says could put that region of Tanzania on many archeologists' radar. "It was only about 20 years ago that people recognized that modern Homo sapiens actually had an African ancestry, and everyone was focused on looking at early Homo sapiens in Europe who appeared around 40,000 years ago," she said. "But we now know that as far as back as around 200,000 years ago, Africa was inhabited by people who were already physically exactly like us today or really close to being the same as us. All of a sudden, it's not Europe in this time period that's really important, it's Africa." Engaging community yields co-operation, opportunity Along with its scientific significance, Willoughby's work may be a linchpin to potential economic growth for the region. Since 2005, when a local cultural officer showed her the sites, she has been sharing information about her research with local citizens, schools and government—opening up opportunities for more research and co-operation. She keeps the region informed of the team's findings through posters distributed around Iringa, and has asked for and accepted assistance from local scholars. Now the community is also looking for her help in establishing the historic sites as a tourist attraction that will benefit the region. Willoughby says she feels fortunate to have the support of the Tanzanian people. She tells people it is a shared history she is uncovering, something she is honoured to be able to do. "They're telling me, 'You're putting Iringa on the map,'" she said. "As long as they keep letting me work there, and keep letting the people working with me work there, we'll be happy." Source : http://phys.org/news/2012-12-humanity-african-ancestry-rewriting-africa.html

|

Excavations in progress within the Still Bay levels at Blombos Cave, southern Cape, South Africa. Courtesy Christopher Henshilwood and the University of the Withwatersrand |

The First Modern Humans Arose in South Africa, Say Researchers (South Africa) 5 December 2012 The synthesis of years of research at prehistoric sites in southern Africa, as represented by research recently published in the Journal of World Prehistory, has led a number of scientists to suggest that South Africa was the primary center for the early development of modern human behavior. This would mean cognitive behavior as manifested in technology much like the material culture of modern hunter-gatherer groups throughout the world today. The new research paper by renowned Wits University archaeologist, Prof. Christopher Henshilwood, is the first detailed summary of Middle Stone Age (280,000 - 50,000 years ago) technologies and cultural remains discovered at a number of sites in southern Africa, artifacts that fall within two established overall "techno-tradition" periods: Still Bay (dated to c. 75,000 – 70,000 years ago) and Howiesons Poort (c. 65,000 – 60,000 years ago). Henshilwood maintains that these periods were significant markers in the development of Homo sapiens behavior in southern Africa. They featured a number of innovations including, for example, the first abstract art (engraved ochre* and engraved ostrich eggshell); the first jewellery (shell beads); the first bone tools; the earliest use of the pressure flaking technique, used in combination with heating to make stone spear points; and the first probable use of stone tipped arrows launched by bow. (See examples pictured below). “All of these innovations, plus many others we are just discovering, clearly show that Homo sapiens in southern Africa at that time were cognitively modern and behaving in many ways like ourselves. It is a good reason to be proud of our earliest, common ancestors who lived and evolved in South Africa and who later spread out into the rest of the world after about 60,000 years,” says Henshilwood. The research also addresses some of the nagging questions about what drove our ancestors to develop these innovative technologies. According to Henshilwood, answers to these questions are, in part, found in demography and climate change, particularly changing sea levels, which have been generally found to be major drivers of innovation and variability in material culture. Henshilwood and his colleagues' extensive research in African archaeology has challenged the previous prevailing model of the emergence of behaviorally modern humans, which has suggested that modern human behavior originated in Europe after about 40,000 years ago. Now, there is increasing evidence for an African origin for behavioral and technological modernity more than 70,000 years ago, and that the earliest origin of all Homo sapiens may lie in Africa and more particulalry southern Africa. Henshilwood writes: “In just the past decade our knowledge of Homo sapiens behaviour in the Middle Stone Age, and in particular of the Still Bay and Howiesons Poort, has expanded considerably. With the benefit of hindsight we may ironically conclude that the origins of ‘Neanthropic Man’, the epitome of behavioural modernity in Europe, lay after all in Africa.” Source : http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/december-2012/article/the-first-modern-humans-arose-in-south-africa-say-researchers

|

A feast fit for ... our prehuman ancestors? While vegetarian, vegan and raw diets can be healthy today - likely far healthier than the typical American diet, to continue to call these diets "natural" for humans, in terms of evolution, is a bit of a stretch. |

Sorry, vegans: Eating meat and cooking food made us human (Africa) 19 November 2012 High caloric intake enabled brains of our prehuman ancestors to grow dramatically Vegetarian, vegan and raw diets can be healthy — likely far healthier than the typical American diet. But to continue to call these diets "natural" for humans, in terms of evolution, is a bit of a stretch, according to two recent, independent studies. Eating meat and cooking food made us human, the studies suggest, enabling the brains of our prehuman ancestors to grow dramatically over a period of a few million years. Although this isn't the first such assertion from archaeologists and evolutionary biologists, the new studies demonstrate, respectively, that it would have been biologically implausible for humans to evolve such a large brain on a raw, vegan diet and that meat-eating was a crucial element of human evolution at least 1 million years before the dawn of humankind. Shhh, don't tell the gorillas At the core of this research is the understanding that the modern human brain consumes 20 percent of the body's energy at rest, twice that of other primates. Meat and cooked foods were needed to provide the necessary calorie boost to feed a growing brain. [ 10 Things You Didn't Know About the Human Brain ] One study, published last month in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, examined the brain sizes of several primates. For the most part, larger bodies have larger brains across species. Yet humans have exceptionally large, neuron-rich brains for our body size, while gorillas — three times more massive than humans — have smaller brains and three times fewer neurons. Why? The answer, it seems, is the gorillas' raw, vegan diet (devoid of animal protein), which requires hours upon hours of eating only plants to provide enough calories to support their mass. Researchers from Brazil, led by Suzana Herculano-Houzel, a neuroscientist at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, calculated that adding neurons to the primate brain comes at a fixed cost of approximately six calories per billion neurons. For gorillas to evolve a humanlike brain, they would need an additional 733 calories a day, which would require another two hours of feeding, the authors wrote. A gorilla already spends as much as 80 percent of the tropic's 12 hours of daylight eating. Similarly, early humans eating only raw vegetation would have needed to munch for more than nine hours a day to consume enough calories, the researchers calculated. Thus, a raw, vegan diet would have been unlikely given the danger and other difficulties of gathering so much food. Cooking makes more foods edible year-round and releases more nutrients and calories from both vegetables and meat, Herculano-Houzel said. "The bottom line is, it is certainly possible to survive on an exclusively raw diet in our modern day, but it was most likely impossible to survive on an exclusively raw diet when our species appeared," Herculano-Houzel told LiveScience. The study puts an upper limit on how big a brain is able to grow while on a premodern raw, vegan diet. But the researchers could not determine when daily cooking began. Was it about 250,000 years ago, when humans were nearly fully evolved with big brains, which is supported by archaeological findings; or was it about 800,000 years ago, when prehumans began their most dramatic brain-growth spurt, an era for which there is little archaeological evidence of controlled fires for cooking? Meet the meat-eater If cooking wasn't routine in the years before the dawn of modern humans, eating meat certainly was. The second study, published in October the journal PLoS ONE, examined the remains of a prehuman toddler who died from malnutrition about 1.5 million years ago. Shards of a skull found in modern-day Tanzania reveal that the child had porotic hyperostosis, a type of spongy bone growth associated with low levels of dietary iron and vitamins B9 and B12, the result of diet lacking animal products in a species that requires them. [ 10 Mysteries of the First Humans ] The child was around the weaning age. So, either the child's mother's breast milk lacked key nutrients, or the child himself did not consume enough nutrients directly from meat or eggs. Either way, the finding implies that meat must have been an integral, and not sporadic, element of the prehuman diet more than 1 million years ago, said the study's lead author, Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo, an archaeologist at Complutense University in Madrid. This supports the theory that meat fueled human brain evolution because meat — from arachnids to zebras — was plentiful on the African savanna, where humans evolved, and is the best package of calories, proteins, fats and vitamin B12 needed for brain growth and maintenance. "Carnivore animals, whether terrestrial or aquatic, are bigger brained than herbivores," Domínguez-Rodrigo told LiveScience. And he added that "there is no [traditional] society that live as vegans," essentially because it wouldn't be possible to get vitamin B12, which is only available in animal products. Vegetables still healthy Both sets of researchers said their conclusion — that cooked food and meat were necessary for human brain development — is not a statement of how the human diet must have been, but rather how it likely was in order to make humans "human." With supermarkets and refrigeration, humans today can and increasingly do eat a vegetarian or vegan diet year-round. And given the amount of heart-stopping saturated fats in factory-produced animal products, a plant-based diet can be healthier. Yet both "extreme sides" of the meat argument — the unapologetic meat eater and the raw vegan — should remember that few so-called natural foods today were around as little as a few hundred years ago, from the modern invention called corn-fed beef to genetically altered strains of Queen Anne's lace called the carrot. From health to the environment, there are many reasons to go vegetarian, go vegan and even go raw, but evolution isn't one of them. Source : http://www.nbcnews.com/id/49888012/ns/technology_and_science-science/#.UXLIeMq5oe9

|

A sculptor's rendering of the hominid Australopithecus afarensis is displayed as part of an exhibition that includes the 3.2 million year old fossilized remains of "Lucy", the most complete example of the species, at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, 28 August 2007 in Houston, Texas. |

Anthropologist finds large differences in gait of early human ancestors (Africa) 12 November 2012 Patricia Ann Kramer, professor of anthropology at the University of Washington, has found that the walking gait between two of our early ancestors was likely so different that it's doubtful they would have done so together, despite being two members of the same species living during roughly the same time period. In her paper published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Kramer outlines how she compared the natural walking speeds of modern humans to those of two members of the Australopithecus afarensis species and found that such large differences existed between two members of our early ancestors that walking together would have been troublesome. In her study, Kramer compared the bones of Lucy, the famous skeletal remains found in Ethiopia, with those of Kadanuumuu (Big Man in Afar) another member of the A. afarensis species unearthed in 2010, though clearly much larger. Because of their difference in height – Lucy would have been about 3.5 feet tall, Big Man approximately 5 – Kramer wondered if they would have been able to walk around together. To find out, she enlisted the aid of 36 children and 16 adults who all agreed to have their leg bones measured and then to be tested walking on a treadmill. Scientists know that people have a natural walking gait that is also the optimal speed for conserving energy. For long legged people, a faster gait is optimal, whereas for those with shorter legs, slower is better. In the case of Lucy and Big Man, the difference in the length of leg bones would have been equivalent to the difference in leg bone length between modern children and adults. She used the data from her volunteers' efforts to create a mathematical formula that allowed her to estimate the natural gait of Lucy and Big Man and found them to be 3.4 feet per second, versus 4.4 feet per second. Such a difference would have meant Lucy would have had to walk a lot faster than normal to keep up with Big Man, or Big Man would have had to walk a lot slower for the two of them to walk around together; an idea that seems counterintuitive because it would mean one or the other would have had to walk at a pace that consumed more energy. Kramer notes that her study includes just two specimens of A. afarensis which are of the opposite gender, and who would have lived some distance from one another. Thus, she suggests it's possible that regional differences were at play, or that males of the time were simply much larger than females, which likely would have meant they spent most of their time apart, similar to modern chimpanzees. Abstract: The estimated lower limb length (0.761–0.793 m) of the partial skeleton of Australopithecus afarensis from Woranso-Mille (KSD-VP-1/1) is outside the previously known range for Australopithecus and within the range of modern humans. The lower limb length of KSD-VP-1/1 is particularly intriguing when juxtaposed against the lower limb length estimate of the other partial skeleton of A. afarensis, AL 288-1 (0.525 m). A sample of 36 children (age, >7 years, trochanteric height = 0.56–0.765 m) and 16 adults (trochanteric height = 0.77–1.00 m) walked at their self-selected slow, preferred, and fast walking velocities, while their oxygen consumption was monitored. Lower limb length and velocity were correlated with slow (P < 0.001, r2 = 0.44), preferred (P < 0.001, r2 = 0.55), and fast (P < 0.001, r2 = 0.69) walking velocity. The relationship between optimal velocity and lower limb length was also determined and lower limb length explained 47% of the variability in optimal velocity. The velocity profile for KSD-VP-1/1 (slow = 0.73–0.75 m/s, preferred = 1.08–1.11 m/s, and fast = 1.48–1.54 m/s) is 36–44% higher than that of AL 288-1 (slow = 0.53 m/s, preferred = 0.78 m/s, and fast = 1.07 m/s). The optimal velocity for AL 288-1 is 1.04 m/s, whereas that for KSD-VP-1/1 is 1.29–1.33 m/s. This degree of lower limb length dimorphism suggests that members of a group would have had to compromise their preferences to walk together or to split into subgroups to walk at their optimal velocity. Source : http://phys.org/news/2012-11-anthropologist-large-differences-gait-early.html

|

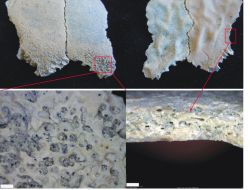

Pinnacle Point, South Africa, with Cave Opening  Microlith Blades  Inside Pinnacle Point Cave |

Small lethal tools have big implications for early modern human complexity (South Africa) 7 November 2012 On the south coast of South Africa, scientists have found evidence for an advanced stone age technology dated to 71,000 years ago at Pinnacle Point near Mossel Bay. This technology, allowing projectiles to be thrown at greater distance and killing power, takes hold in other regions of Africa and Eurasia about 20,000 years ago. When combined with other findings of advanced technologies and evidence for early symbolic behavior from this region, the research documents a persistent pattern of behavioral complexity that might signal modern humans evolved in this coastal location. These findings were reported in the article "An Early and Enduring Advanced Technology Originating 71,000 Years Ago in South Africa" in the November 7 issue of the journal Nature. "Every time we excavate a new site in coastal South Africa with advanced field techniques, we discover new and surprising results that push back in time the evidence for uniquely human behaviors," said co-author Curtis Marean, project director and Arizona State University professor in the Institute of Human Origins, a research center of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change. The reported technology focused on the careful production of long, thin blades of stone that were then blunted (called "backing") on one edge so that they could be glued into slots carved in wood or bone. This created light armaments for use as projectiles, either as arrows in bow and arrow technology, or more likely as spear throwers (atlatls). These provide a significant advantage over hand cast spears, so when faced with a fierce buffalo (or competing human), having a projectile weapon of this type increases the killing reach of the hunter and lowers the risk of injury. The stone used to produce these special blades was carefully transformed for easier flaking by a complex process called "heat treatment," a technological advance also appearing early in coastal South Africa and reported by the same research team in 2009. "Good things come in small packages," said Kyle Brown, a skilled stone tool replicator and co-author on the paper, who is an honorary research associate with the University of Cape Town, South Africa. "When we started to find these very small carefully made tools, we were glad that we had saved and sorted even the smallest of our sieved materials. At sites excavated less carefully, these microliths may have been discarded in the back dirt or never identified in the lab." Prior work showed that this microlithic technology appear briefly between 65,000 and 60,000 years ago during a worldwide glacial phase, and then it was thought to vanish, thus showing what many scientists have come to accept as a "flickering" pattern of advanced technologies in Africa. The so-called flickering nature of the pattern was thought to result from small populations struggling during harsh climate phases, inventing technologies, and then losing them due to chance occurrences wiping out the artisans with the special knowledge. "Eleven thousand years of continuity is, in reality, an almost unimaginable time span for people to consistently make tools the same way," said Marean. "This is certainly not a flickering pattern." The appearance and disappearance is more likely a function of the small sample of well-excavated sites in Africa. Because of this small sample, each new site has a high probability of adding a novel observation. The African sample is a tiny fraction of the known European sample from the same time period. "This is why continued and well-funded fieldwork in Africa is of the highest scientific priority if we want to learn about what it means to be human, and where and when it happened," said Marean. The site where this technology was discovered is called Pinnacle Point 5-6 (PP5-6). This spectacular site preserves about 14 meters of archaeological sediment dating from approximately 90,000 to 50,000 years ago. The documentation of the age and span of the technology was made possible by an unprecedented fieldwork commitment of nine, two-month seasons (funded by the National Science Foundation and Hyde Family Foundation) where every observed item related to human behavior was plotted directly to a computer using a "total station." A total station is a surveying instrument that digitally captures points where items are found to create a 3D model of the excavation. Almost 200,000 finds have been plotted to date, and excavations continue. This was joined to over 75 optically stimulated luminescence dates by project geochronologist Zenobia Jacobs at the University of Wollongong (Australia), creating the highest resolution stone-age sequence from this time span. "As an archaeologist and scientist, it is a privilege to work on a site that preserves a near perfect layered sequence capturing almost 50,000 years of human prehistory," said Brown, who codirected excavations at PP5-6. "Our team has done a remarkable job of identifying some of the subtle but important clues to just how innovative these early humans on the south coast were." Research on stone tools and Neanderthal anatomy strongly suggests that Neanderthals lacked true projectile weapons. "When Africans left Africa and entered Neanderthal territory they had projectiles with greater killing reach, and these early moderns probably also had higher levels of pro-social (hyper-cooperative) behavior. These two traits were a knockout punch. Combine them, as modern humans did and still do, and no prey or competitor is safe," said Marean. "This probably laid the foundation for the expansion out of Africa of modern humans and the extinction of many prey as well as our sister species such as Neanderthals." Source : http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2012-11/asu-slt110512.php

|

One model of human migration based on mitochondrial DNA (dates in thousands of years). Image: Wikimedia |

Human expansion from Africa comes into focus (Africa) 1 November 2012 A new, comprehensive review of human anthropological and genetic records gives the most up-to-date story of the “Out of Africa” expansion that occurred about 45,000 to 60,000 years ago. This expansion, detailed by three Stanford geneticists Henn, Cavalli-Sforza, and Feldman presents an up-to-date version of the model. In the recent study is published in this edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences they conclude it had a dramatic effect on human genetic diversity, which persists in present-day populations. As a small group of modern humans migrated out of Africa into Eurasia and the Americas, their genetic diversity was substantially reduced. Previous genomic projects In studying these migrations, genomic projects haven’t fully taken into account the rich archaeological and anthropological data available, and vice versa. This review integrates both sides of the story and provides a foundation that could lead to better understanding of ancient humans and, possibly, genomic and medical advances. “People are doing amazing genome sequencing, but they don’t always understand human demographic history” that can help inform an investigation, said review co-author Brenna Henn, a postdoctoral fellow in genetics at the Stanford School of Medicine who has a PhD in anthropology from Stanford. “We wanted to write this as a primer on pre-human history for people who are not anthropologists.” “This model of the Out of Africa expansion provides the framework for testing other anthropological and genetic models,” Henn said “The basic notion is that all of these disciplines have to be considered simultaneously when thinking about movements of ancient populations,” said Marcus Feldman, a professor of biology at Stanford and the senior author of the paper. “What we’re proposing is a story that has potential to explain any of the fossil record that subsequently becomes available, and to be able to tell what was the size of the population in that place at that time.” The anthropological information can inform geneticists when they investigate certain genetic changes that emerge over time. For example, geneticists have found that genes for lactose intolerance and gluten sensitivity began to emerge in populations expanding into Europe around 10,000 years ago. The anthropological record helps explain this: It was around this time that humans embraced agriculture, including milk and wheat production. The populations that prospered – and thus those who survived to pass on these mutations – were those who embraced these unnatural food sources. This, said Feldman, is an example of how human movements drove a new form of natural selection. Expanding populations and bottleneck diversity Populations that expand from a small founding group can also exhibit reduced genetic diversity – known as a “bottleneck” – a classic example being the Ashkenazi Jewish population, which has a fairly large number of genetic diseases that can be attributed to its small number of founders. When this small group moved from the Rhineland to Eastern Europe, reproduction occurred mainly within the group, eventually leading to situations in which mothers and fathers were related. This meant that offspring often received the same deleterious gene from each parent and, as this process continued, ultimately resulted in a population in which certain diseases and cancers are more prevalent. “If you know something about the demographic history of populations, you may be able to learn something about the reasons why a group today has a certain genetic abnormality – either good or bad,” Feldman said. “That’s one of the reasons why in our work we focus on the importance of migration and history of mixing in human populations. It helps you assess the kinds of things you might be looking for in a first clinical assessment. It doesn’t have the immediacy of prescribing chemotherapy – it’s a more general look at what’s the status of human variability in DNA, and how might that inform a clinician.” Source : http://www.pasthorizonspr.com/index.php/archives/11/2012/human-expansion-from-africa-comes-into-focus

|

|

New Stanford analysis provides fuller picture of human expansion from Africa (Africa) 22 October 2012 A comprehensive analysis of the anthropological and genetic history of humans' expansion out of Africa could lead to medical advances. By Bjorn Carey Integrating anthropological information into models can better inform geneticists when they investigate certain genetic changes that emerge over time. (Photo: Bruce Rolff/Shutterstock) A new, comprehensive review of humans' anthropological and genetic records gives the most up-to-date story of the "Out of Africa" expansion that occurred about 45,000 to 60,000 years ago. This expansion, detailed by three Stanford geneticists, had a dramatic effect on human genetic diversity, which persists in present-day populations. As a small group of modern humans migrated out of Africa into Eurasia and the Americas, their genetic diversity was substantially reduced. In studying these migrations, genomic projects haven't fully taken into account the rich archaeological and anthropological data available, and vice versa. This review integrates both sides of the story and provides a foundation that could lead to better understanding of ancient humans and, possibly, genomic and medical advances. "People are doing amazing genome sequencing, but they don't always understand human demographic history" that can help inform an investigation, said review co-author Brenna Henn, a postdoctoral fellow in genetics at the Stanford School of Medicine who has a PhD in anthropology from Stanford. "We wanted to write this as a primer on pre-human history for people who are not anthropologists." This model of the Out of Africa expansion provides the framework for testing other anthropological and genetic models, Henn said, and will allow researchers to constrain various parameters on computer simulations, which will ultimately improve their accuracy. "The basic notion is that all of these disciplines have to be considered simultaneously when thinking about movements of ancient populations," said Marcus Feldman, a professor of biology at Stanford and the senior author of the paper. "What we're proposing is a story that has potential to explain any of the fossil record that subsequently becomes available, and to be able to tell what was the size of the population in that place at that time." The anthropological information can inform geneticists when they investigate certain genetic changes that emerge over time. For example, geneticists have found that genes that allowed humans to tolerate lactose and gluten began to emerge in populations expanding into Europe around 10,000 years ago. The anthropological record helps explain this: It was around this time that humans embraced agriculture, including milk and wheat production. The populations that prospered - and thus those who survived to pass on these mutations - were those who embraced these unnatural food sources. This, said Feldman, is an example of how human movements drove a new form of natural selection. Populations that expand from a small founding group can also exhibit reduced genetic diversity - known as a "bottleneck" - a classic example being the Ashkenazi Jewish population, which has a fairly large number of genetic diseases that can be attributed to its small number of founders. When this small group moved from the Rhineland to Eastern Europe, reproduction occurred mainly within the group, eventually leading to situations in which mothers and fathers were related. This meant that offspring often received the same deleterious gene from each parent and, as this process continued, ultimately resulted in a population in which certain diseases and cancers are more prevalent. "If you know something about the demographic history of populations, you may be able to learn something about the reasons why a group today has a certain genetic abnormality - either good or bad," Feldman said. "That's one of the reasons why in our work we focus on the importance of migration and history of mixing in human populations. It helps you assess the kinds of things you might be looking for in a first clinical assessment. It doesn't have the immediacy of prescribing chemotherapy - it's a more general look at what's the status of human variability in DNA, and how might that inform a clinician." The study is published in the current edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and was co-authored by Feldman's longtime collaborator, population geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza of Stanford and the Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele in Italy. Source : http://news.stanford.edu/pr/2012/pr-genetic-human-evolution-102212.html

|

|

Study Suggests Early Humans Ate Meat 1.5 Million Years Ago (Tanzania, East Africa) 3 October 2012 Close examination of a 1.5 million-year-old skull fragment orginally discovered at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania reveals features that indicate anemia, a nutrional deficiency caused by the lack of vitamin B, a vitamin commonly acquired through the consumption of meat. The discovery was made by an international team of researchers led by Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo from Complutense University, Madrid, and it suggests that early human ancestors ate meat earlier in history than previously thought. The skull fragment, dated to approximately 1.5 million years B.P. and identified as belonging to a child aged less than two, shows bone lesions that commonly result from a lack of B-vitamins in the diet. Previous studies have indicated that early hominids may have consumed meat, but it was uncertain if they ate meat on a regular basis, or only occasionally. The lesions in the bone fragment suggests, according to the study authors, that meat-eating was common enough that not consuming it could lead to anemia. The child likely could have acquired vitamins associated with meat through the mother's milk before weaning. Nutritional deficiencies such as anemia are most common at weaning, when a child's diet commonly changes. The researchers suggest that the child may have died after starting to eat solid foods lacking meat or, if the child was still breastfeeding, the mother may have been nutritionally deficient because of the lack of meat in her diet. Based on the study results, "early humans were hunters, and had a physiology adapted to regular meat consumption at least 1.5 million years ago", according to the researchers. Source : http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/september-2012/article/study-suggests-early-humans-ate-meat-1-5-million-years-ago

|

A Hadza hunter in Tanzania. The skills need to kill animals for food have now been dated back to two million years ago. Photograph: Nigel Pavitt/Corbis |

Humans hunted for meat 2 million years ago (Tanzania, East Africa) 23 September 2012 Evidence from ancient butchery site in Tanzania shows early man was capable of ambushing herds up to 1.6 million years earlier than previously thought Ancient humans used complex hunting techniques to ambush and kill antelopes, gazelles, wildebeest and other large animals at least two million years ago. The discovery – made by anthropologist Professor Henry Bunn of Wisconsin University – pushes back the definitive date for the beginning of systematic human hunting by hundreds of thousands of years. Two million years ago, our human ancestors were small-brained apemen and in the past many scientists have assumed the meat they ate had been gathered from animals that had died from natural causes or had been left behind by lions, leopards and other carnivores. But Bunn argues that our apemen ancestors, although primitive and fairly puny, were capable of ambushing herds of large animals after carefully selecting individuals for slaughter. The appearance of this skill so early in our evolutionary past has key implications for the development of human intellect. "We know that humans ate meat two million years ago," said Bunn, who was speaking in Bordeaux at the annual meeting of the European Society for the study of Human Evolution (ESHE). "What was not clear was the source of that meat. However, we have compared the type of prey killed by lions and leopards today with the type of prey selected by humans in those days. This has shown that men and women could not have been taking kill from other animals or eating those that had died of natural causes. They were selecting and killing what they wanted." That finding has major implications, he added. "Until now the oldest, unambiguous evidence of human hunting has come from a 400,000-year-old site in Germany where horses were clearly being speared and their flesh eaten. We have now pushed that date back to around two million years ago." The hunting instinct of early humans is a controversial subject. In the first half of the 20th century, many scientists argued that our ancestors' urge to hunt and kill drove us to develop spears and axes and to evolve bigger and bigger brains in order to handle these increasingly complex weapons. Extreme violence is in our nature, it was argued by fossil experts such as Raymond Dart and writers like Robert Ardrey, whose book African Genesis on the subject was particularly influential. By the 80s, the idea had run out of favour, and scientists argued that our larger brains evolved mainly to help us co-operate with each other. We developed language and other skills that helped us maintain complex societies. "I don't disagree with this scenario," said Bunn. "But it has led us to downplay the hunting abilities of our early ancestors. People have dismissed them as mere scavengers and I don't think that looks right any more." In his study, Bunn and his colleagues looked at a huge butchery site in the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. The carcasses of wildebeest, antelopes and gazelles were brought there by ancient humans, most probably members of the species Homo habilis, more than 1.8 million years ago. The meat was then stripped from the animals' bones and eaten. "We decided to look at the ages of the animals that had been dragged there," said Benn. "By studying the teeth in the skulls that were left, we could get a very precise indication of what type of meat these early humans were consuming. Were they bringing back creatures that were in their prime or were old or young? Then we compared our results with the kinds of animals killed by lions and leopards." The results for several species of large antelope Bunn analysed showed that humans preferred only adult animals in their prime, for example. Lions and leopards killed old, young and adults indiscriminately. For small antelope species, the picture was slightly different. Humans preferred only older animals, while lions and leopards had a fancy only for adults in their prime. "For all the animals we looked at, we found a completely different pattern of meat preference between ancient humans and other carnivores, indicating that we were not just scavenging from lions and leopards and taking their leftovers. We were picking what we wanted and were killing it ourselves." Bunn believes these early humans probably sat in trees and waited until herds of antelopes or gazelles passed below, then speared them at point-blank range. This skill, developed far earlier than suspected, was to have profound implications. Once our species got a taste for meat, it was provided with a dense, protein-rich source of energy. We no longer needed to invest internal resources on huge digestive tracts that were previously required to process vegetation and fruit, which are more difficult to digest. Freed from that task by meat, the new, energy-rich resources were then diverted inside our bodies and used to fuel our growing brains. As a result, over the next two million years our crania grew, producing species of humans with increasingly large brains – until this carnivorous predilection produced Homo sapiens. Source : http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2012/sep/23/human-hunting-evolution-2million-years

|

|

Extensive DNA Study Sheds Light on Modern Human Origins (Africa) 20 September 2012 A new study of human genetic variation in sub-Saharan Africa, where modern Homo sapiens are believed to have originated, helps to reveal the region's rich genetic history, with implications for understanding the complexity of early modern human evolution. The largest genomic study ever conducted among the Khoe and San population groups in southern Africa reveals that these groups are descendants of the earliest diversification event in the history of all humans - some 100,000 years ago, well before the largely accepted 'out-of-Africa' migration date range of modern humans. Some 220 individuals from different regions in southern Africa participated in the research, leading to the analysis of around 2.3 million DNA variants per individual – the largest such study ever conducted. The research was conducted by a group of international scientists, including Dr. Carina Schlebusch and Assistant Professor Mattias Jakobsson from Uppsala University in Sweden and Professor Himla Soodyall from the Human Genomic Diversity and Disease Research Unit in the Health Faculty at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. "The deepest divergence of all living people occurred some 100,000 years ago, well before modern humans migrated out of Africa and about twice as old as the divergences of central African Pygmies and East African hunter-gatherers and from other African groups," says lead author Dr Carina Schlebusch, a Wits University PhD-graduate now conducting post-doctoral research at Uppsala University in Sweden. According to her colleague Matthias Jakobsson, these deep divergences among African populations have important implications and consequences when the history of all humankind is deciphered. The deep structure and patterns of genetic variation suggest a complex population history of the peoples of Africa. "The human population has been structured for a long time," says Jakobsson, "and it is possible that modern humans emerged from a non-homogeneous group." The study also found surprising stratification among Khoe-San groups. For example, the researchers estimate that the San populations from northern Namibia and Angola separated from the Khoe and San populations living in South Africa as early as 25,000 – 40,000 years ago. "There is astonishing ethnic diversity among the Khoe-San group, and we were able to see many aspects of the colorful history that gave rise to this diversity in their DNA", said Schlebusch. The study further indicates how pastoralism first spread to southern Africa in combination with the Khoe culture. From archaeological and ethnographic studies it has been suggested that pastoralism was introduced to the Khoe in southern Africa before the arrival of Bantu-speaking farmers, but it has been unclear if this event had any genetic impact. The Nama, a pastoralist Khoe group from Namibia showed great similarity to 'southern' San groups. "However, we found a small but very distinct genetic component that is shared with East Africans in this group, which may be the result of shared ancestry associated with pastoral communities from East Africa," says Schlebusch. With the genetic data the researchers could see that the Khoe pastoralists originated from a Southern San group that adopted pastoralism with genetic contributions from an East African group – a group that would have been the first to bring pastoralist practices to southern Africa. The study also revealed evidence of local adaptation in different Khoe and San groups. For example, the researchers found that there was evidence for selection in genes involved in muscle function, immune response, and UV-light protection in local Khoe and San groups. These could be traits linked with adaptations to the challenging environments in which the ancestors of present-day San and Khoe were exposed to that have been retained in the gene pool of local groups. The researchers also looked for signals across the genome of ancient adaptations that happened before the historical separation of the Khoe-San lineage from other humans. "Although all humans today carry similar variants in these genes, the early divergence between Khoe-San and other human groups allowed us to zoom-in on genes that have been fast-evolving in the ancestors of all of us living on the planet today," said Pontus Skoglund from Uppsala University. Among the strongest candidates were genes involved in skeletal development that may have been crucial in determining the characteristics of anatomically modern humans. The researchers are now making the genome-wide data freely available: "Genetic information is getting more and more important for medical purposes. In addition to illuminating their history, we hope that this study is a step towards Khoe and San groups also being a part of that revolution," says Schlebusch. Another author, Professor Mike de Jongh from University of South Africa adds, "It is important for us to communicate with the participants prior to the genetic studies, to inform individuals about the nature of our research, and to also go back to not only share the results with them, but also to explain the significance of the data for recapturing their heritage, to them." Source : http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/september-2012/article/extensive-dna-study-sheds-light-on-modern-human-origins

|

At 500,000 years, the dating of this skull of Homo heidelbergensis clashed with previous DNA dates for Neanderthal origins. J. TRUEBA/MSF/SPL |

Studies slow the human DNA clock (Africa) 18 September 2012 Revised estimates of mutation rates bring genetic accounts of human prehistory into line with archaeological data. The story of human ancestors used to be writ only in bones and tools, but since the 1960s DNA has given its own version of events. Some results were revelatory, such as when DNA studies showed that all modern humans descended from ancestors who lived in Africa more than 100,000 years ago. Others were baffling, suggesting that key events in human evolution happened at times that flatly contradicted the archaeology. Now archaeologists and geneticists are beginning to tell the same story, thanks to improved estimates of DNA’s mutation rate — the molecular clock that underpins genetic dating1–4. “It’s incredibly vindicating to finally have some reconciliation between genetics and archaeology,” says Jeff Rose, an archaeologist at the University of Birmingham, UK. Archaeologists and geneticists may now be able to tackle nuanced questions about human history with greater confidence in one another’s data. “They do have to agree,” says Aylwyn Scally, an evolutionary genomicist at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Hinxton, UK. “There was a real story.” The concept of a DNA clock is simple: the number of DNA letter differences between the sequences of two species indicates how much time has elapsed since their last common ancestor was alive. But for estimates to be correct, geneticists need one crucial piece of information: the pace at which DNA letters change. Geneticists have previously estimated mutation rates by comparing the human genome with the sequences of other primates. On the basis of species-divergence dates gleaned — ironically — from fossil evidence, they concluded that in human DNA, each letter mutates once every billion years. “It’s a suspiciously round number,” says Linda Vigilant, a molecular anthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. The suspicion turned out to be justified. In the past few years, geneticists have been able to watch the molecular clock in action, by sequencing whole genomes from dozens of families5 and comparing mutations in parents and children. These studies show that the clock ticks at perhaps half the rate of previous estimates, says Scally. In a review published on 11 September1,Scally and his colleague Richard Durbin used the slower rates to reevaluate the timing of key splits in human evolution. “If the mutation rate is halved, then all the dates you estimate double,” says Scally. “That seems like quite a radical change.” Yet the latest molecular dates mesh much better with key archaeological dates. Take the 400,000–600,000-year-old Sima de Los Huesos site in Atapuerca, Spain, which yielded bones attributed to Homo heidelbergensis, the direct ancestors of Neanderthals. Genetic studies have suggested that earlier ancestors of Neanderthals split from the branch leading to modern humans much more recently, just 270,000–435,000 years ago. A slowed molecular clock pushes this back to a more comfortable 600,000 years ago (see ‘Better agreement over the human story’). A slower molecular clock could also force scientists to re-think the timing of later turning points in prehistory, including the migration of modern humans out of Africa. Genetic studies of humans around the world have suggested that the ancestors of Europeans and Asians left Africa about 60,000 years ago. That date caused many to conclude that 100,000-year-old human fossils discovered in Israel represented a dead-end migration rather than the beginning of a global exodus, says Scally. Scally’s calculations put “out of Africa” closer to 120,000 years ago, suggesting that the Israeli sites represent a launching pad for the spread of humans into Asia and Europe. The latest genetic dates also fit with several sites in the Middle East that contain tools apparently made by modern humans but dating to around 100,000 years ago. At that time, sea levels between Africa and the Arabian Peninsula were lower than they are now, and a wetter climate would have made the peninsula lush and habitable, perhaps beckoning modern humans out of Africa. Rose, who works one such site, in Oman, says that he “has been over the moon” since reading Scally and Durbin’s paper. The revised molecular clock may also help to settle a debate over whether humans ventured further into Asia more than 60,000 years ago, says Michael Petraglia, an archaeologist at the University of Oxford, UK, who favours an early date. Although a slowed molecular clock may harmonize the story of human evolution, it does strange things when applied further back in time, says David Reich, an evolutionary geneticist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts. “You can’t have it both ways.” For instance, the slowest proposed mutation rate puts the common ancestor of humans and orang-utans at 40 million years ago, he says: more than 20 million years before dates derived from abundant fossil evidence. This very slow clock has the common ancestor of monkeys and humans co-existing with the last dinosaurs. “It gets very complicated,” deadpans Reich. Some researchers, including Scally, have proposed that the mutation rate may have slowed over the past 15 million years, thereby accounting for such discrepancies. Fossil evidence suggests that ancestral apes were smaller than living ones, and small animals tend to reproduce more quickly, speeding the mutation rate. Little concrete evidence supports this idea, says Reich. He agrees that the molecular clock must be slower than was thought, but says that the question is how slow. “My strong view right now is that the true value of the human mutation rate is an open question.” Source : http://www.nature.com/news/studies-slow-the-human-dna-clock-1.11431

|

Part of the ~500 thousand-year-old Kathu Pan 1 lithic collection, which is housed at the McGregor Museum, Kimberley, South Africa. [Image courtesy of Jayne Wilkins] |

Stone-Tipped Spears Used Much Earlier Than Thought, Say Researchers (South Africa) 8 September 2012 Evidence from South Africa shows that human ancestors were making stone-tipped spears 500,000 years ago. A University of Toronto-led team of anthropologists has found evidence that human ancestors used stone-tipped weapons for hunting 500,000 years ago - 200,000 years earlier than previously thought. "This changes the way we think about early human adaptations and capacities before the origin of our own species," says Jayne Wilkins, a PhD candidate in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Toronto and lead author of a new study in Science. "Although both Neandertals and humans used stone-tipped spears, this is the first evidence that the technology originated prior to or near the divergence of these two species," says Wilkins. Attaching stone points to spears – known as 'hafting' – was an important advance in hunting weaponry for early humans. Hafted tools require more effort and foreplanning to manufacture, but a sharp stone point on the end of a spear can increase its killing power. Hafted spear tips are common in Stone Age archaeological sites after 300,000 years ago. This new study shows that they were also used in the early Middle Pleistocene, a period associated with Homo heidelbergensis (a hominid species that has been suggest by many scientists to be ancestral to humans) and the last common ancestor of Neandertals and modern humans. "It now looks like some of the traits that we associate with modern humans and our nearest relatives can be traced further back in our lineage", Wilkins says. Wilkins and colleagues from Arizona State University and the University of Cape Town examined 500,000-year-old stone points from the South African archaeological site of Kathu Pan 1 and determined that they had functioned as spear tips. The points were recovered during 1979-1982 excavations by Peter Beaumont of the McGregor Museum. In 2010, a team directed by Chazan reported that the point-bearing deposits at Kathu Pan 1 dated to ~500,000 years ago using optically stimulated luminescence and U-series/electron spin resonance methods. The dating analyses were carried out by Naomi Porat, Geological Survey of Israel, and Rainer Grün, Australian National University. In this latest study of the stone points led by Wilkins, point function was determined by comparing wear on the ancient points to damage inflicted on modern experimental points used to spear a springbok carcass target with a calibrated crossbow. This method has been used effectively to study weaponry from more recent contexts in the Middle East and southern Africa. The stone points exhibit certain types of breaks that occur more commonly when they are used to tip spears compared to other uses. "The archaeological points have damage that is very similar to replica spear points used in our spearing experiment," says Wilkins. "This type of damage is not easily created through other processes." The findings are reported in the paper "Evidence for Early Hafted Hunting Technology" published in the November 16, 2012 issue of Science. Other authors contributing to the study are Benjamin Schoville from Arizona State University, Kyle Brown of the University of Cape Town, and University of Toronto archaeologist Michael Chazan. Funding for the research was provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the National Science Foundation, and the Hyde Family Foundation. Logistical support came from the South African Heritage Resources Agency and the McGregor Museum, Kimberley, South Africa. Source : http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/september-2012/article/stone-tipped-spears-used-much-earlier-than-thought-say-researchers

|

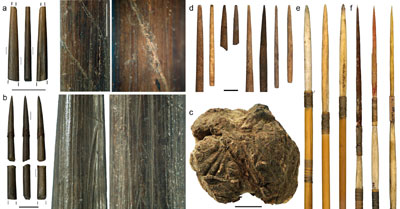

Objects found in the archaeological site called Border Cave include a) a wooden digging stick; b) a wooden poison applicator; c) a bone arrow point decorated with a spiral incision filled with red pigment; d) a bone object with four sets of notches; e) a lump of beeswax; and f) ostrich eggshell beads and marine shell beads used as personal ornaments. (Francesco d'Errico and Lucinda Backwell / July 30, 2012) |