This painting, known as the Porterville Galleon, is believed to be a rare indigenous record of colonial activity in South Africa. Photo courtesy of the Trust for African Rock Art

|

In South Africa, Colonialism Was Written on Stone

12 December 2016

At the base of a steep outcrop near the small South African town of Porterville, outside Cape Town, is a painting of a wooden ship. Its masts and rigging are clearly visible, traced on a lined and rutted rock surface. Three flags blow to the left; a fourth blows to the right. This suggests that the artist did not fully understand sailing technology, an incongruity that can be readily explained. Archaeologists believe that the ship represents an extremely rare record of encroaching colonial activity, painted by someone whose ancestral land was being wrested away. Today, the painting footnotes an era of conquest that had devastating consequences for local people.

Whoever painted the ship trekked far inland before leaving his or her mark: the nearest coastal bays lie 100 kilometers to the west. The painting, dubbed the Porterville Galleon, is found in one of the richest rock art areas in southern Africa. The parched and rugged mountain range 200 kilometers north of Cape Town known as the Cederberg has several thousand ocher paintings on boulders and sandstone ledges. The images record the lives and rituals of the indigenous peoples who inhabited the Cape of Good Hope for hundreds of generations before European settlers - first from the Netherlands, and then Britain - took control of the land.

Some paintings found near the Cederberg are more than 3,500 years old, left behind by ancient San hunter-gatherer societies. They depict animals, humans, and therianthropes—people with hybrid animal features metamorphosing during trance states. Geometric patterns, handprints, and paintings of domestic sheep overlay some of these images, which are thought to date to the appearance of Khoi pastoralists 2,000 years ago. The ship painting marks a more recent and dramatic historical contact.

The South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA) incorporated the painting into a logo for its National Survey of Underwater Heritage in 2003. Around that time, SAHRA manager John Gribble wrote that the image, which has been speculatively dated to the early 18th century, was an "important graphic reminder of the meeting of precolonial and colonial maritime worlds." John Parkington, professor emeritus of archaeology at the University of Cape Town, is more cautious about the art's provenance. "It's a painting on a rock," he says. "You can never be completely sure who put it there, that it wasn't some joker in the 1960s. But it's likely that the image is authentic: there are much older paintings, produced with what seems to be the same iron oxide pigments, nearby."

According to Parkington, indigenous societies had been "wrecked, disempowered, and dispossessed" by the time the ship was painted. "Things had changed dramatically for local people. Settlers were expanding north from Cape Town, claiming new territory. Many herders started working for white ranchers. Hunter-gatherers were scarce. While the old traditions and languages probably still existed, it's doubtful many new paintings were being made."

There are at least five known rock paintings of ships in South Africa; according to Parkington, the Porterville Galleon is the "clearest and most interesting." Other colonial-era rock paintings show wagons, men smoking tobacco pipes, and women in ankle-length dresses. These images mark the end of a visual archive extending back thousands of years. Khoi and San groups were largely annihilated by the mid-19th century, engulfed and splintered by colonial development. Many people died of smallpox, a fate shared by millions of indigenous peoples on the other side of the Atlantic when the Americas were colonized. In South Africa, more people still were killed in systematic horseback raids by settler militias - a genocide, according to the Cape Town historian Mohamed Adhikari and several other scholars and activists.

"It was a period of immense disruption," Parkington says. "We don't know why the artist traveled to the mountains from the sea, but this painting is evidence that they did."

Slowly fading, the image provokes questions that cannot be resolved. Who painted it? What message was it supposed to convey? When the ship loomed near shore, its flags rippling, what did the artist see?

Source: https://www.hakaimagazine.com/article-short/south-africa-colonialism-was-written-stone

|

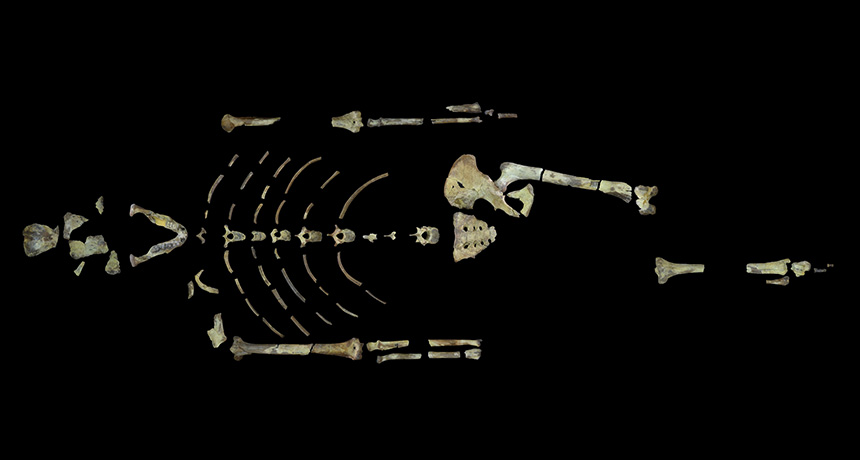

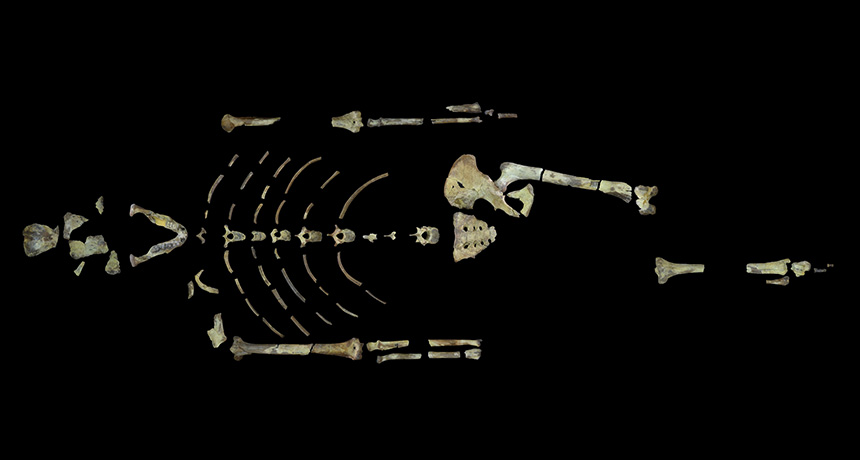

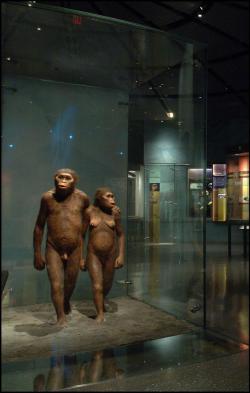

Arm strong. Relatively long, robustly built upper arms let Lucy, the famous 3.2-million-year-old hominid, spend a lot of time in trees, scientists say. Scans of Lucy's fossils also suggest she walked less efficiently than people today do

|

Buff upper arms let Lucy climb trees

30 November 2016

Lucy didn't let an upright stance ground her. This 3.2-million-year-old Australopithecus afarensis, hominid evolution's best-known fossil individual, strong-armed her way up trees, a new study finds.

Her lower body was built for walking. But exceptional upper-body strength, approaching that of chimpanzees, enabled Lucy to hoist herself into trees or onto tree branches, paleoanthropologist Christopher Ruff of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and his colleagues report November 30 in PLOS ONE.

Lucy, and presumably other members of her species, "combined walking on two legs with a significant amount of tree climbing," says coauthor John Kappelman, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Texas at Austin. A Kappelman-led team concluded earlier this year that, based on numerous bone breaks, Lucy fell to her death from a tree, either while climbing or sleeping (SN: 9/17/16, p. 16). That's a controversial claim, dismissed by some researchers as a misreading of bone damage caused by the fossilization process.

Debate about whether A. afarensis spent much time in trees goes back to shortly after the discovery of Lucy's partial skeleton in 1974. Additional discoveries of A. afarensis fossils have only intensified disputes between those who regard the ancient species as primarily designed for walking and others convinced that Lucy's crowd split time between walking and tree climbing (SN: 12/1/12, p. 16; SN: 7/17/10, p. 5).

Ruff's team measured the internal structure and strength of Lucy's two surviving upper arm bones and one upper leg bone, including the knob at the top of the upper leg that forms the hip joint. Data came from high-resolution X-ray CT scans taken in 2008 while her remains were in the United States for a museum tour.

These scans were compared with those of present-day people, chimps and bonobos, as well as 26 fossil hominids. These hominids - including both australopithecines like Lucy, as well as early members of the human genus, Homo - date to between 2.6 million and 600,000 years ago.

Lucy's long, weight-bearing upper arms most closely resemble the anatomy of chimps, the scientists say. Studies of various living animals, including humans and chimps, indicate that daily behaviors during growth influence the development of limb bones. Thus, it's plausible that Lucy pulled herself into trees from an early age, adding to the strength and length of her upper arms, the team proposes.

Although Lucy walked upright, she had a less efficient gait than that of people today and Homo erectus individuals dating to between 1.6 million and 700,000 years ago, the researchers say. The stress of supporting a robust upper body with a slighter lower body would have interfered with Lucy's two-legged stride, they hold. Traits such as a relatively small hip joint and short legs limited Lucy's ability to walk long distances, the investigators add.

Ruff's study supports proposals over the last few decades that, for her size, Lucy had longer, stronger arms and smaller hip joints than people now do, says paleoanthropologist Carol Ward of the University of Missouri School of Medicine in Columbia. It's plausible that a small hip joint slightly undermined Lucy's stride, but that hasn't been conclusively demonstrated, Ward adds.

Biological anthropologist Philip Reno of Penn State takes a harder line. "This new analysis does not resolve any of the debates regarding the use of tree climbing or the effectiveness of upright walking in australopithecines." Radical, humanlike changes to the pelvis and foot in Lucy's species suggest that her large upper arms were simply evolutionary holdovers from hominids' tree-dwelling ancestors, not the consequences of extensive tree climbing, Reno argues. It's hard to say how Lucy's relatively small hip joint interacted with many other skeletal and muscular forces affecting an upright gait, he adds.

The big question, in Ward's view, is whether skeletal changes in early Homo conducive to walking and running arose as a result of largely abandoning tree climbing or for other reasons, such as an increasing emphasis on arms and hands capable of manipulating objects in precise ways.

Source: https://www.sciencenews.org/article/buff-upper-arms-let-lucy-climb-trees

|

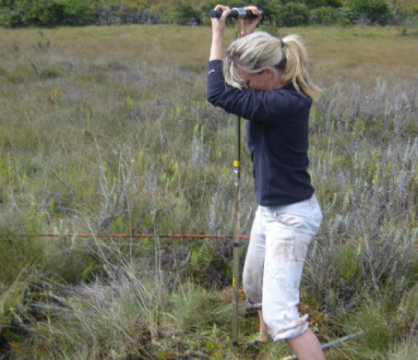

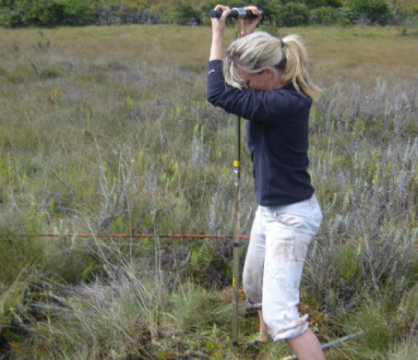

Researchers took layers of peat from a bog where material, such as pollen and charcoal were found.

Credit: Image courtesy of University of York

|

Peat bog reveals more than 1,000 years of Tanzanian history

8 November 2016

Scientists have charted more than 1,000 years of Tanzanian environmental history using sediments extracted from a peat bog. Working in the Eastern Arc Mountains of Tanzania, where only 15% of the tropical forests remain compared to 1,000 years ago, the team aimed to identify if the region's rich biodiversity had altered over the years and what major events in history, such as the emergence of the ivory trade in the Victorian period, might have contributed to changes in the forests.

==========

Scientists at the University of York have charted more than 1,000 years of Tanzanian environmental history using sediments extracted from a peat bog.

Working in the Eastern Arc Mountains of Tanzania, where only 15% of the tropical forests remain compared to 1,000 years ago, the team aimed to identify if the region's rich biodiversity had altered over the years and what major events in history, such as the emergence of the ivory trade in the Victorian period, might have contributed to changes in the forests.

Researchers took layers of peat from a bog, where material, such as pollen, charcoal from fires, and other remains from the environment, are trapped and preserved over many years in the sediments. Using radiocarbon dating techniques they were able to reconstruct how the ecosystem changed over the past 1,200 years.

Research results show that the forest ecosystem remains quite stable -- the same as it was more than 1,000 years go. This suggests that climate change has not yet impacted on the forest, possibly due to its proximity to moist, fresh air from the Indian Ocean. Results also show, however, that the shrinking size of the forest is largely due to human activity.

Dr Robert Marchant, from the University of York's Department of Environment, said: "The Eastern Arc Mountains are a biodiversity hotspot, but it has been under threat from human activities for many years.

"Forests that are now separated by some miles were once joined together, but what we don't know is just how much these changes have impacted on its biodiversity over time and what activity had the biggest impact on its environment.

"With this new data we were able to see at what points the environment started to change and through historical records we matched these changes to particular events in time. For example we start to see pollen from New World crops, such as maize, start to spread from around 1750, as well as evidence of forest plantations of pine trees, and eucalyptus from the Colonial period, which are not native to the environment.

"Maize crop enters our record at a time when large parts of the forest were cut down and farmed to accommodate the European ivory trades -- or caravan trades as they were known."

In the 1860s European and Arab traders to the region slaughtered up to 70,000 elephants for their ivory each year. It was traded to other countries for the production of a range of items, from ornaments, piano keys, cutlery handles, jewellery, and as part of exhibits. It not only decimated the elephant population, but also the impact the animals had on the forest composition and distribution.

Dr Jemma Finch, who carried out the work at York, but is now based at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, added: "We start to see large increases in charcoal in the record at about the time colonial forest offices arrive to cut trees for timber trading.

"It is only in the 1980s that we start to see less human activity in the records. This was the time when a timber ban was put in place and forest preservation policies established."

The researchers highlight that although human activity has been the biggest impact on the forest over the years, and biodiversity is relatively stable today despite the diminished size of the forest, climate change is still a threat to its future.

Dr Marchant said: "This research can help us identify the best areas of the forest to conserve for sustainable growth, where plant and animal life and, most importantly, the ecosystem services that sustain the Tanzania nation, are most likely to be supported.

"If predictions about a wetter, but much warmer, climate in the future are accurate, then now is the time to start to invest in this important landscape so that it is still here in the next 1,000 years."

The research is published in the journal The Holocene.

Source: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/11/161108130459.htm

|

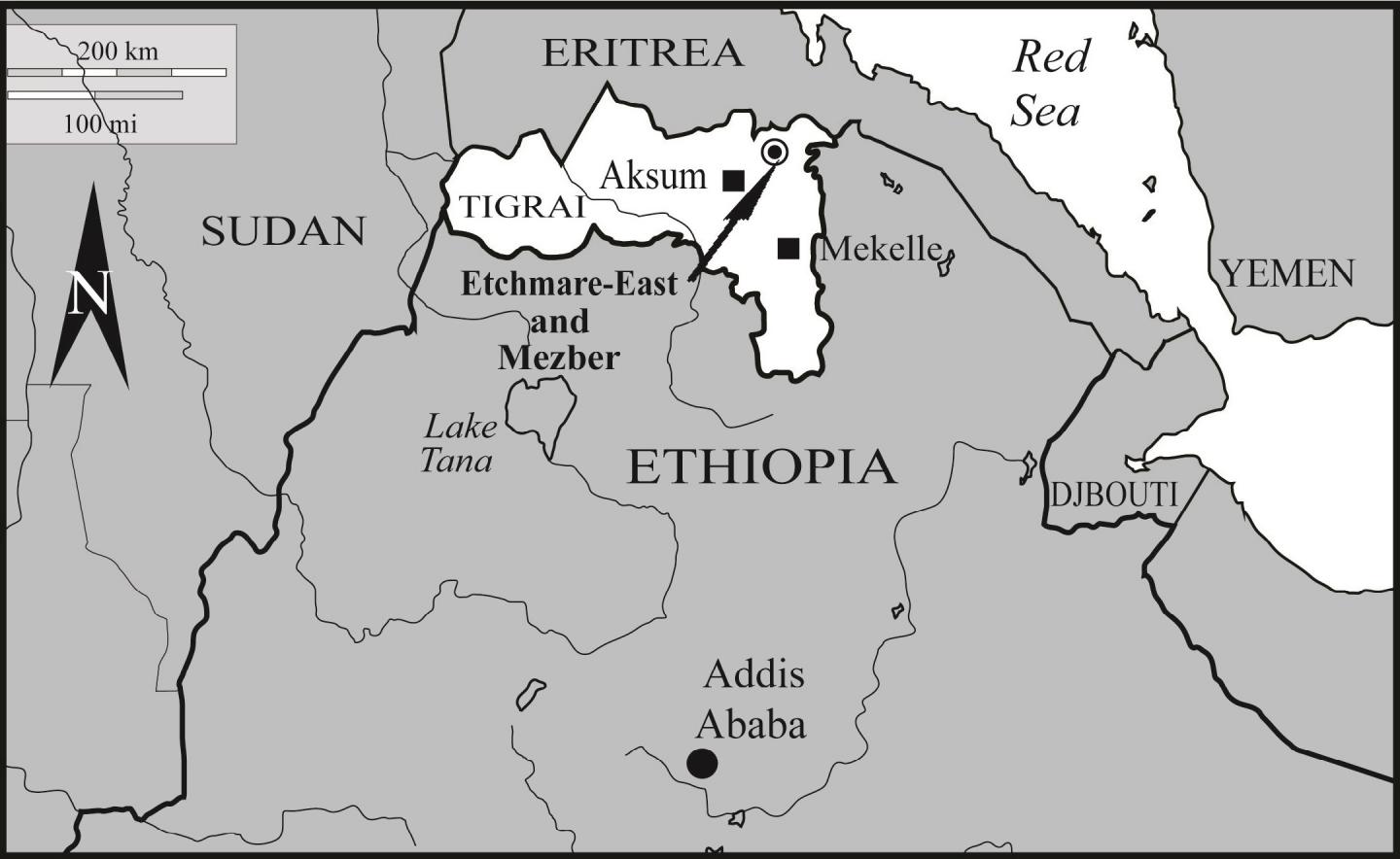

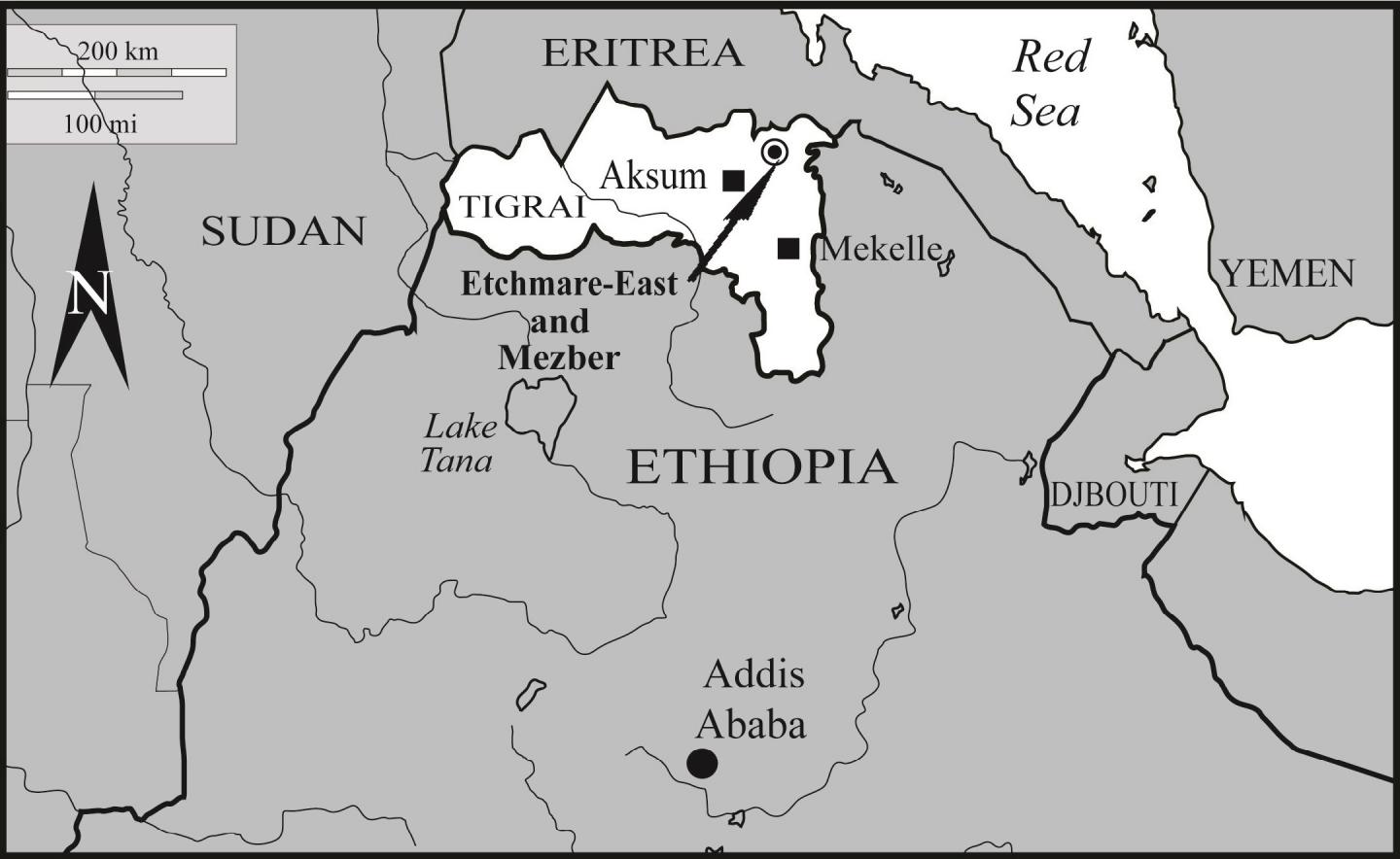

This is the location of the Mezber archaeological site in northern Ethiopia

|

How the chicken crossed the Red Sea

2 November 2016

The discarded bone of a chicken leg, still etched with teeth marks from a dinner thousands of years ago, provides some of the oldest known physical evidence for the introduction of domesticated chickens to the continent of Africa, research from Washington University in St. Louis has confirmed.

Based on radiocarbon dating of about 30 chicken bones unearthed at the site of an ancient farming village in present-day Ethiopia, the findings shed new light on how domesticated chickens crossed ancient roads -- and seas -- to reach farms and plates in Africa and, eventually, every other corner of the globe.

"Our study provides the earliest directly dated evidence for the presence of chickens in Africa and points to the significance of Red Sea and East African trade routes in the introduction of the chicken," said Helina Woldekiros, lead author and a postdoctoral anthropology researcher in Arts & Sciences at Washington University.

The main wild ancestor of today's chickens, the red junglefowl Gallus gallus is endemic to sub-Himalayan northern India, southern China and Southeast Asia, where chickens were first domesticated 6,000-8,000 years ago. Now nearly ubiquitous around the world, the offspring of these first-domesticated chickens are providing modern researchers with valuable clues to ancient agricultural and trade contacts.

The arrival of chickens in Africa and the routes by which they both entered and dispersed across the continent are not well known. Previous research based on representations of chickens on ceramics and paintings, plus bones from other archaeological sites, suggested that chickens were first introduced to Africa through North Africa, Egypt and the Nile Valley about 2,500 years ago.

The earliest bone-based evidence of chickens in Africa dates to the late first millennium B.C., from the Saite levels at Buto, Egypt -- approximately 685-525 B.C.

This study, published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, pushes that date back by hundreds of years. Co-authored by Catherine D'Andrea, professor of archaeology at Simon Fraser University in Canada, the research also suggests that the earliest introductions may have come from trade routes on the continent's eastern coast.

"Some of these bones were directly radiocarbon dated to 819-755 B.C., and with charcoal dates of 919-801 B.C. make these the earliest chickens in Africa," Woldekiros said. "They predate the earliest known Egyptian chickens by at least 300 years and highlight early exotic faunal exchanges in the Horn of Africa during the early first millennium B.C."

Despite their widespread, modern-day importance, chicken remains are found in small numbers at archaeological sites. Because wild relatives of the galliform chicken species are plentiful in Africa, this study required researchers to sift through the remnants of many small bird species to identify bones with the unique sizes and shapes that are characteristic of domestic chickens.

Woldekiros, the project's zooarchaeologist, studied the chicken bones at a field lab in northern Ethiopia and confirmed her identifications using a comparative bone collection at the Institute of Paleoanatomy at Ludwig Maximillian University in Munich.

Excavated by a team of researchers led by D'Andrea of Simon Fraser, the bones analyzed for this study were recovered from the kitchen and living floors of an ancient farming community known as Mezber. The rural village was located in northern Ethiopia about 30 miles from the urban center of the pre-Aksumite civilization. The pre-Aksumites were the earliest people in the Horn of Africa to form complex, urban-rural trading networks.

Linguistic studies of ancient root words for chickens in African languages suggest multiple introductions of chickens to Africa following different routes: from North Africa through the Sahara to West Africa; and from the East African coast to Central Africa. Scholars also have demonstrated the biodiversity of modern-day African village chickens through molecular genetic studies.

"It is likely that people brought chickens to Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa repeatedly over long period of time: over 1,000 years," Woldekiros said. "Our archaeological findings help to explain the genetic diversity of modern Africans chickens resulting from the introduction of diverse chicken lineages coming from early Arabian and South Asian context and later Swahili networks."

These findings contribute to broader stories of ways in which people move domestic animals around the world through migration, exchange and trade. Ancient introductions of domestic animals to new regions were not always successful. Zooarchaeological studies of the most popular domestic animals such as cattle, sheep, goats and pigs have demonstrated repeated introductions as well as failures of new species in different regions of the world.

"Our study also supports the African Red Sea coast as one possible early route of introduction of chickens to Africa and the Horn," Woldekiros said. "It fits with ways in which maritime exchange networks were important for global distribution of chicken and other agricultural products. The early dates for chickens at Mezber, combined with their presence in all of the occupation phases at Mezber and in Aksumite contexts 40 B.C.- 600 A.D. in other parts of Ethiopia, demonstrate their long-term success in northern Ethiopia."

Source: https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2016-11/wuis-htc110216.php

|

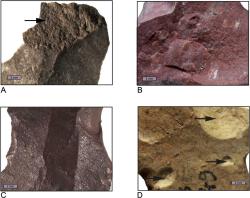

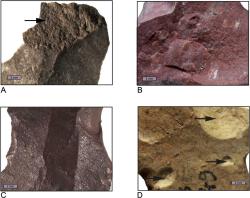

Humans living in South Africa in the Middle Stone Age may have used advanced heating techniques to produce silcrete blades, according to a study published Oct. 19, 2016 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Anne Delagnes from the CNRS (PACEA - University of Bordeaux, France) and colleagues. Credit: Delagnes et al (2016)

|

Extensive heat treatment in Middle Stone Age silcrete tool production in South Africa

19 October 2016

Humans living in South Africa in the Middle Stone Age may have used advanced heating techniques to produce silcrete blades, according to a study published October 19, 2016 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Anne Delagnes from the CNRS (PACEA - University of Bordeaux, France) and colleagues.

Middle Stone Age humans in South Africa developed intentional heat treatment of silcrete rock over 70,000 years ago to facilitate the flaking process by modifying the rock properties - the first evidence of a transformative technology. However, the exact role of this important development in the Middle Stone Age technological repertoire was not previously clear. Delagnes and colleagues addressed this issue by using a novel non-destructive approach to analyze the heating technique used in the production of silcrete artifacts at Klipdrift Shelter, a recently discovered Middle Stone Age site located on the southern Cape of South Africa, including unheated and heat-treated comparable silcrete samples from 31 locations around the site.

The authors noted intentional and extensive heat treatment of over 90% of the silcrete, highlighting the important role this played in silcrete blade production. The heating step appeared to occur early during the blade production process, at an early reduction stage where stone was flaked away to shape the silcrete core. The hardening, toughening effect of the heating step would therefore have impacted all subsequent stages of silcrete tool production and use.

The authors suggest that silcrete heat treatment at the Klipdrift Shelter may provide the first direct evidence of the intentional and extensive use of fire applied to a whole lithic chain of production. Along with other fire-based activities, intentional heat treatment was a major asset for Middle Stone Age humans in southern Africa, and has no known contemporaneous equivalent elsewhere.

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/fall-2016/article/extensive-heat-treatment-in-middle-stone-age-silcrete-tool-production-in-south-africa2

|

Black Bashi-Bazouk: Oil on canvas in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008: given by Mrs. Charles Wrightsman

|

Scientists map genome of African diaspora in the Americas

11 October 2016

Researchers at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus along with colleagues at Johns Hopkins University and other institutions have conducted the largest ever genome sequencing of populations with African ancestry in the Americas.

The scientists, for the first time, have created a massive genetic catalog of the African diaspora in this hemisphere. It offers a unique window into the striking genetic variety of the population while opening the door to new ways of understanding and treating diseases specific to this group.

The study was published today in the journal Nature Communications.

"The African Diaspora in the Western Hemisphere represents one of the largest forced migrations in history and had a profound impact on genetic diversity in modern populations," said the study's principal investigator Kathleen Barnes, PhD, director of the Colorado Center for Personalized Medicine at CU Anschutz. "Yet this group has been largely understudied."

Barnes said those of African ancestry in the Americas suffer a disproportionate burden of disability, disease and death from common chronic illnesses like asthma, diabetes and other ailments. The reasons why, remain largely unknown.

With that question in mind Barnes and her colleagues, with support from the NIH's National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, created the `Consortium on Asthma among African-ancestry Populations in the Americas' or CAAPA. They sequenced the genome of 642 people of African ancestry from 15 North, Central and South American and Caribbean populations plus Yoruba-speaking individuals from Ibadan, Nigeria. The ultimate goal of the study is to better understand why they are more susceptible to asthma in the Americas. But the result was a wide-ranging genetic catalogue unlike any other.

The African genome is the oldest and most varied on earth. Africa is where modern humans evolved before migrating to Europe, Asia and beyond.

Barnes and her team are finding changes in the DNA of Africans in the Americas that put them at higher risk for certain diseases. Perhaps one reason for this is the amount of genetic material they carry from other populations including those of European ancestry and American Indians.

"Patterns of genetic distance and sharing of single nucleotide variations among these populations reflect the unique population histories in each of the North, Central and South American and Caribbean island destinations of West African slaves, with their particular Western European colonial and Native American populations," the study said.

For example, the researchers showed that the mean African ancestry varied widely among populations depending on where they were settled, from 27% of Puerto Ricans to 89% of Jamaicans. In places like the Dominican Republic, Brazil, Honduras and Colombia there was also significant Native American ancestry as well.

Untangling this genetic history will take years, but Barnes said the catalogue is a good start. The data will serve as an important resource for disease mapping studies in those with African ancestry.

"This will contribute to the public database and give clinicians more information to better predict and track human disease," Barnes said. "It will allow us to tailor clinical to specific individuals based on their ethnic and racial backgrounds."

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/fall-2016/article/scientists-map-genome-of-african-diaspora-in-the-americas

|

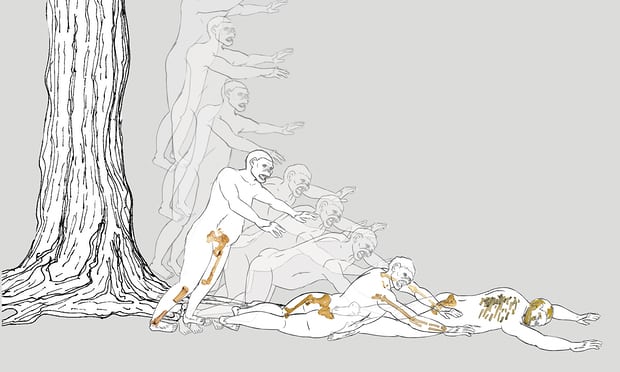

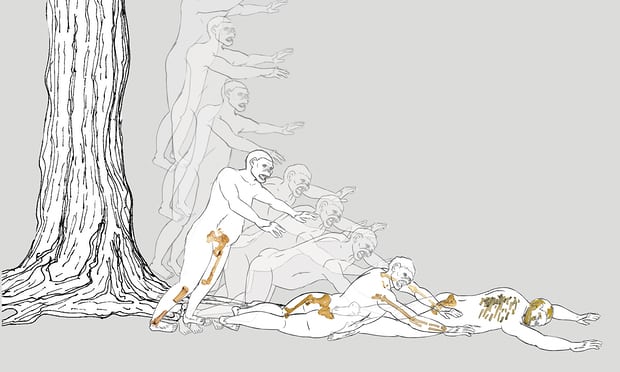

Branching of... a still from a reconstruction video of human ancestor Lucy the ape falling from tree to sustain injuries. Photograph: John Kappelman/University of Texas at Austin

|

Family tree fall: human ancestor Lucy died in arboreal accident, say scientists

29 August 2016

Researchers claim analysis of 3.2m-year-old skeleton of 'grandmother of humanity' shows injuries consistent with those of humans falling on hard ground, but others query findings

The ancient human ancestor known as Lucy may have met her death more than 3m years ago when she tumbled out of a tree and crashed to the woodland floor, a team of US researchers claim.

A fresh analysis of the "grandmother of humanity" points out a number of cracks in the fossil bones that the scientists say match traumatic fractures seen in humans who suffer serious injuries from high falls on to hard ground.

"The consistency of the pattern of fractures with what we see in fall victims leads us to propose that it was a fall that was responsible for Lucy's death," said John Kappelman, an anthropologist who led the study at the University of Texas in Austin. "I think the injuries were so severe that she probably died very rapidly after the fall."

But the claims, published in the prestigious journal Nature, were roundly dismissed by scientists who spoke to the Guardian. They point out that a lot can happen to a skeleton in 3.2m years. Lucy's body may have been trampled by stampeding beasts before sediment covered the bones and gradually encased them in rock.

"There is a myriad of explanations for bone breakage," said Donald Johanson at Arizona State University, who discovered Lucy more than 40 years ago in the Afar region of Ethiopia. "The suggestion that she fell out of a tree is largely a "just-so story" that is neither verifiable nor falsifiable, and therefore unprovable."

Tim White, a paleoanthropologist at the University of California in Berkeley, said the cracks were no more than routine fossil damage. "If paleontologists were to apply the same logic and assertion to the many mammals whose fossilised bones have been distorted by geological forces, we would have everything from gazelles to hippos, rhinos, and elephants climbing and falling from high trees," he said.

Lucy was discovered in 1974 when Johanson and his student, Tom Gray, were searching for ancient animal bones on the parched terrain near the village of Hadar in northern Ethiopia. The chance finding of a piece of arm bone led them to uncover more remains of an ape-like animal. Eventually, they gathered about 40% of the skeleton.

That evening as the team celebrated at camp the Beatles song Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds came on providing the scientists with a name for their discovery. The species, Australopithecus afarensis, meaning "southern Ape from Afar", walked upright, but had long, strong arms and curved fingers, making Lucy more adept at life in the trees than modern humans.

Kappelman became intrigued by some of the cracks in Lucy's bones after examining high resolution x-ray scans of the fossils. The cracks had been described before and put down to natural processes such as erosion and fossilisation. But Kappelman thought there might be another explanation.

Working with Stephen Pearce, an orthopaedic surgeon, the scientists identified cracks in more than a dozen bones, ranging from the skull and spine to the ankles, shins, knees and pelvis, which look like compressive fractures sustained in a fall. One injury to the right shoulder matches the kind of fracture seen when people instinctively put their arms out to save themselves, the scientists believe. Kappelman calls it "a unique signature" for a fall and evidence that the individual was conscious at the time.

From the scientists' calculations, Lucy, who weighed less than 30kg, could have suffered similar injuries in a fall from about 15 metres. If Australopithecus afarensis climbed trees to nest, the animals could have spent hours a day at this or even greater heights. “We know that chimps fall out of trees and often it’s because they step on a branch that turns out to be rotten, and boom, down they come,” said Kappelman.

"Based on clinical literature these are severe trauma events. We have not been able to come up with a reasonable way that these could be fractured postmortem with the bones lying on the surface or even if the dead body was being trampled on. If somebody is trampled on the bone breaks in a different way. It doesn't break compressively," said Kappelman.

But Johanson is not impressed. The cracks on Lucy's bones are similar to the damage seen on other early human and ancient mammal fossils throughout Africa and the rest of the world, he said. "We don't know how long the fossilisation process takes, but the enormous set of forces placed on the bones during the build up of sediments covering the bones is a significant factor in promoting damage and breakage," he added.

One of White's major complaints is that the scientists fail to prove beyond doubt that the cracks in Lucy's bones occurred around the time of death. “Such defects created by natural geological forces of sediment pressure and mineral growth are very common in fossil assemblages. They often confuse clinicians and amateurs who imagine them to have happened around the time of death," White said. "Every single element of the Lucy fossil has cracks. The authors cherry pick the ones that they imagine to be evidence of a fall from a tree, leaving the others unexplained and unexamined."

Kappelman concedes that we can never know for sure what happened. "None of us were there. We didn’t see Lucy die," he said. "Thinking about testing this idea, it’s hard to get someone to fall out of a tree, but we have tests going on every single day in every emergency room on planet Earth when people walk in with fractures from falls," he said.

In pondering Lucy's death, she came back to life, Kappelman added. For the first time she became a living, breathing individual, because I could understand what I propose to be her death. We have all fallen down. For an instant in time you can identify with her and imagine exactly what this individual, who lived over 3m years ago, was doing at that instant."

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/aug/29/family-tree-fall-human-ancestor-lucy-died-in-arboreal-accident-say-scientists

|

Student Adama Athie, left, sits next to Ibrahima Thiaw, 50, center, and fellow students, Djidere Balde, Madick Gueye, Pape Leity Diop and Aicha Kamite off the shore of Goree Island in Dakar, Senegal in May. (Jane Hahn/For The Washington Post)

|

The incredible quest to find the African slave ships that sank in the Atlantic

20 August 2016

OFF THE COAST OF DAKAR, SENEGAL — The archaeologist rose in the bow of the speedboat, pointing to the choppy waters where the 18th-century slave ship had gone down.

"It's somewhere over there," Ibrahima Thiaw said.

Off the western tip of mainland Africa lie some of the most important vestiges of the transatlantic slave trade: the wreckage of ships that sank, carrying thousands of African men, women and children to the Americas. But despite historians' immense interest in that period, no one has ever tried to excavate them. Until now.

For years, the wrecks were considered too hard to find. The work was too expensive. And few African researchers were willing to take on the project in countries where the slave trade is often considered a source of shame — not a subject worthy of study.

Thiaw, a tall 50-year-old archaeologist from rural Senegal, is one of the pioneers trying to find the wrecks. There has been only one known excavation of a ship that went down off the African coast while carrying slaves — the São José, found thousands of miles away, off South Africa. Artifacts from the vessel will be displayed at the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture, opening next month. Thiaw hopes his discoveries will eventually be featured by the museum, too.

"The stories that will help us understand the slave trade, this crucial moment in human history, are down there," Thiaw said, gazing from the boat into the Atlantic Ocean as he began the search on a bright day in May. But as he would discover over the following months, it wouldn't be easy.

Senegal was a major exporter of slaves for about 400 years. When Thiaw was in school, though, that history was barely discussed. As a boy, he visited Goree Island, just off the coast of Dakar, where a tour guide told him about the slaves waiting, shackled, for boats headed for the Americas. "After listening to him," he recalled, "I screamed."

It was the beginning of an obsession. His parents were farmers, but Thiaw decided to be an archaeologist, studying at the University of Dakar and then earning a PhD at Rice University in Houston. Some of his friends and family joked that he was "searching for garbage."

Senegal had became known worldwide for its landmarks of the slave trade, particularly on Gorée, a major entrepot, or trading center. But the scholarship turned out to be shaky. In the 1990s, American researchers claimed that those sites had been misidentified. The famed "Door of No Return" was not in fact a final departure point for slaves, they said, but probably just a door in a private residence. For Thiaw, the controversy reinforced his commitment to archaeological research.

"I decided I would find my own true stories," he recalled.

In 2000, Thiaw did some research on Goree Island that helped explain how and where slaves lived, and supported the idea that the island was probably a major employer of domestic slaves, not just an exporter. He found a shackle that he keeps in a box in his office. But many of the island’s relics had been worn down by tourism or buried under construction. He came to realize that some of the most meaningful artifacts of the slave trade were elsewhere. More than 1,000 slave ships had sunk around the world, according to archival records. Archaeologists had barely scratched the surface of what they held.

Thiaw had one logistical problem, though: He didn't know how to swim.

So two years ago, an instructor taught him to paddle. A few months later, he was enrolled in a scuba-diving course. A few months after that, he helped teach his graduate students at Cheikh Anta Diop University to dive, too.

His timing was perfect. The Smithsonian had just announced funding for research on the slave trade, as part of the international Slave Wrecks Project. Suddenly, Thiaw had a benefactor, at least for the first phase of the work, which cost about $35,000.

"We needed a committed archaeologist who wanted to bring his work underwater," said Paul Gardullo, curator of the new African American History Museum. "That's Ibrahima."

In May, Thiaw and six of his graduate students boarded a boat off a Dakar beach and sped into the Atlantic chop for their first research voyage. The archaeologist handed out typewritten pages to his students with the names of boats.

There were two French vessels, the Nanette and the Bonne Amitie, that had disappeared in 1774 and 1790. There was a British sloop called Racehorse that had vanished in November 1780. All were thought to have sunk just miles off the coast. And there were hints of many others.

"There's so much down there," Thiaw said eagerly.

He and his team dragged a torpedo-shaped device along the ocean floor that held a magnetometer, which can detect buried metal. The data from the device would be sent for analysis to South Africa. Once enough evidence emerged that a wreck had been found, the team would start intensive diving.

No one on the team wanted to think about how long their quest might last, or whether their funding would be sufficient. It took researchers more than a decade to locate and document the remains of the São José off Cape Town, South Africa. That discovery was announced only last year.

But for Thiaw, the physical difficulty of finding the wrecks was only part of the challenge.

In Senegal, where President Obama traveled in 2013 to see the remains of the slave trade's prisons and ports, slavery is rarely a subject of academic interest.

"We've turned to contemporary issues, to discussing about the future," former Senegalese prime minister Aminata Touré said in an interview. "Why focus on such a bad part of our history?"

During the last presidential election, in 2012, then-President Abdoulaye Wade argued that his opponent, Macky Sall, couldn't be elected because he was "the descendant of slaves." Sall won the election, but only after rejecting that claim and citing his "non-slave" lineage.

That bias is even embedded in the local language, Wolof. If someone is acting badly, Senegalese will often call him a "jaam" — a slave.

"It's like it's something in your blood, in your genes, with all the dishonor and everything that goes with it," Thiaw said in an interview in his office. "It’s not something people want to delve into, or learn more about."

He paused.

"I feel like we haven't abolished it yet."

The reluctance to research or teach about slavery exists across much of West Africa, where, in the 20th century, nations emerging from colonial rule encouraged historians to study themes that might build a sense of national identity.

Part of the sensitivity regarding slavery comes from the complicity of some Africans in the trade — merchants who profited from the sale of men and women, and sometimes owned slaves themselves.

Thiaw wanted to tell the story of the lives of slaves — what they brought with them on their journeys, what they scrawled on the walls of the boat. The more intimate the details, he thought, the harder it would be for his countrymen to brush off the past.

As he put it: "Finding a good wreck could help us disentangle this — to show that the slave is the victim."

For many years, what was known about the slaves' "middle passage" across the Atlantic came largely from the documents of slave traders, things like tax records, receipts and diaries. It was useful information, but difficult to verify and clinical in its description of the inhumanity shown to slaves.

Finding untouched artifacts, Gardullo said, meant "a chance to fill the silences in the written record."

But, as Thiaw found, the quest could be frustrating. In the first few weeks of searching, he and his team made a few preliminary dives, but they discovered only sunken fishing boats. Thiaw sent one of his students to the country's national archives to look for more leads. Three months after their first voyage, they are still waiting for analysis of the data they gathered underwater and sent to South Africa.

Now Thiaw is worrying about lining up additional funding, and keeping his graduate students involved, because some will graduate soon.

"If I can't keep them focused on this program, maybe they will move on," Thiaw said. "I'm getting nervous."

It was hardly the first time he'd grown anxious over his research. But this time the stakes felt higher. He could almost see the Atlantic from his office window, with all the wreckage buried underneath.

Source: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/the-incredible-quest-to-find-the-african-slave-ships-that-sank-in-the-atlantic/2016/08/17/25dd6080-cf5b-46e0-b896-ea0512311bdd_story.html?utm_term=.081c7d443476

|

The shapes of the fossil and modern footprints are nearly indistinguishable. Credit: Kevin Hatala / Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

|

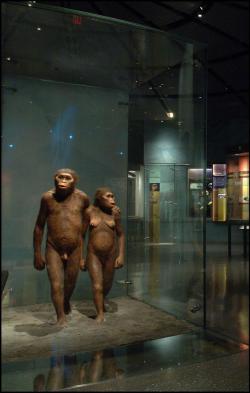

Homo erectus walked as we do

13 July 2016

Fossil bones and stone tools can tell us a lot about human evolution, but certain dynamic behaviours of our fossil ancestors - things like how they moved and how individuals interacted with one another - are incredibly difficult to deduce from these traditional forms of paleoanthropological data. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, along with an international team of collaborators, have recently discovered multiple assemblages of Homo erectus footprints in northern Kenya that provide unique opportunities to understand locomotor patterns and group structure through a form of data that directly records these dynamic behaviours*. Using novel analytical techniques, they have demonstrated that these H. erectus footprints preserve evidence of a modern human style of walking and a group structure that is consistent with human-like social behaviours.

Habitual bipedal locomotion is a defining feature of modern humans compared with other primates, and the evolution of this behaviour in our clade would have had profound effects on the biologies of our fossil ancestors and relatives. However, there has been much debate over when and how a human-like bipedal gait first emerged in the hominin clade, largely because of disagreements over how to indirectly infer biomechanics from skeletal morphologies. Likewise, certain aspects of group structure and social behaviour distinguish humans from other primates and almost certainly emerged through major evolutionary events, yet there has been no consensus on how to detect aspects of group behaviour in the fossil or archaeological records.

In 2009, a set of 1.5-million-year-old hominin footprints was discovered at a site near the town of Ileret, Kenya. Continued work in this region by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and an international team of collaborators, has revealed a hominin trace fossil discovery of unprecedented scale for this time period - five distinct sites that preserve a total of 97 tracks created by at least 20 different presumed Homo erectus individuals. Using an experimental approach, the researchers have found that the shapes of these footprints are indistinguishable from those of modern habitually barefoot people, most likely reflecting similar foot anatomies and similar foot mechanics. "Our analyses of these footprints provide some of the only direct evidence to support the common assumption that at least one of our fossil relatives at 1.5 million years ago walked in much the same way as we do today," says Kevin Hatala, of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and The George Washington University.

Based on experimentally derived estimates of body mass from the Ileret hominin tracks, the researchers have also inferred the sexes of the multiple individuals who walked across footprint surfaces and, for the two most expansive excavated surfaces, developed hypotheses regarding the structure of these H. erectus groups. At each of these sites there is evidence of several adult males, implying some level of tolerance and possibly cooperation between them. Cooperation between males underlies many of the social behaviours that distinguish modern humans from other primates. "It isn't shocking that we find evidence of mutual tolerance and perhaps cooperation between males in a hominin that lived 1.5 million years ago, especially Homo erectus, but this is our first chance to see what appears to be a direct glimpse of this behavioural dynamic in deep time," says Hatala.

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/summer-2016/article/homo-erectus-walked-as-we-do

|

This file photo taken on May 17, 2016 shows a primitive rock painting, one of a galaxy of colourful animal and human sketches to adorn the caves in the rocky hills of this arid wilderness in northern Somalia, near Hargeisa, home to Africa's earliest known and most pristine rock art.

|

Rocky future for Somalia's ancient cave art

26 June 2016

Centuries have passed since Neolithic artists swirled red and white colour on the cliffs of northern Somalia, painting antelopes, cattle, giraffes and hunters carrying bows and arrows.

Today, the paintings at Laas Geel in the self-declared state of Somaliland retain their fresh brilliance, providing vivid depictions of a pastoralist history dating back some 5,000 years or more.

"These paintings are unique. This style cannot be found anywhere in Africa," said Abdisalam Shabelleh, the site manager from Somaliland's Ministry of Tourism.

Related Stories

Then he points to a corner, where the paint fades and peels off the rocks. "If nothing is done now, in 20 years it could all have disappeared," he added.

The site is in dire need of protection. "We don't have the knowledge, the experience or the financial resources. We need support," Shabelleh said.

The paintings, some 50 kilometres (30 miles) from Hargeisa, capital of Somaliland, are considered among the oldest and best preserved rock art sites in Africa but are protected only by a few guards who ask visitors not to touch the paintings.

Diplomatic donor legal limbo

Applications for assistance by Somaliland's government have gone unheeded. A former British protectorate, Somaliland declared independence from the rest of Somalia when war erupted following the overthrow of president Mohamed Siad Barre in 1991, but it is not recognised by the international community.

The "lack of recognition" of the country blocks the cave's protection, said Xavier Gutherz, the former head of the French archaeology team that discovered the site in 2002.

Amazed by the remarkable condition of the paintings as well as their previously unknown style, the archaeologist asked for the cave's listing as a UNESCO world heritage site.

But that request was refused because Somaliland is not recognised as a separate nation. "Only state parties to the World Heritage Convention can nominate sites for World Heritage status," said a UNESCO spokeswoman.

Requests for funding from donor countries face the same legal and diplomatic headache.

Centuries of isolation and local beliefs that the site was haunted and the art the work of evil spirits may have contributed to Laas Geel's protection.

But since their discovery, the cave paintings have become one of the main attractions for visitors to Somaliland.

'Part of our blood'

Around a thousand visitors each year endure long stretches of rugged terrain and travel with armed escorts to reach Laas Geel, and numbers are growing.

"The concerns of Somaliland are legitimate," said Gutherz, who has identified key areas to tackle to help protect the site.

"We have to secure the site, arrange access paths, strengthen the rocks that could collapse, divert rainwater runoff and improve the training of guards," he said.

With a major development planned for Somaliland's main port at Berbera, the number of visitors is expected to increase.

Ahmed Ibrahim Awale, who heads local environmental group Candlelight, said that dust is adding to the damage at the caves.

"The increased human activity in the area, trampling on the bare gravelly soil, does not allow the natural regeneration of plants," Awale said. "The resulting dust particles may contribute to the fading of the paintings."

Archaeologists say that Laas Geel may only be one of many treasures awaiting discovery in the vast rocky plains stretching towards the tip of the Horn of Africa.

Musa Abdi Jama, one of the guardians of the site, sees in the ancient site of Laas Geel the hope of a new nation to be, flying the flag for the cultural identity and uniqueness of Somaliland.

"Here, it was once known as the home of djinn (spirits) by the local nomadic people, who used to slaughter domestic animals for sacrifice in order to live there in peace," Jama said.

"Now it is part of our blood. Tomorrow, God willing, it will be the first place in Somaliland to be internationally recognized."

Source: http://www.ctvnews.ca/sci-tech/rocky-future-for-somalia-s-ancient-cave-art-1.2962595

|

Ghana farmers in the field of a demonstration farm. Trees for the Future, Wikimedia Commons

|

700-year-old West African soil technique could help mitigate climate change

16 June 2016

A farming technique practised for centuries by villagers in West Africa, which converts nutrient-poor rainforest soil into fertile farmland, could be the answer to mitigating climate change and revolutionising farming across Africa.

A global study, led by the University of Sussex, which included anthropologists and soil scientists from Cornell, Accra, and Aarhus Universities and the Institute of Development Studies, has for the first-time identified and analysed rich fertile soils found in Liberia and Ghana.

They discovered that the ancient West African method of adding charcoal and kitchen waste to highly weathered, nutrient poor tropical soils can transform the land into enduringly fertile, carbon-rich black soils which the researchers dub 'African Dark Earths'.

From analysing 150 sites in northwest Liberia and 27 sites in Ghana researchers found that these highly fertile soils contain 200-300 percent more organic carbon than other soils and are capable of supporting far more intensive farming.

Professor James Fairhead, from the University of Sussex, who initiated the study, said: "Mimicking this ancient method has the potential to transform the lives of thousands of people living in some of the most poverty and hunger stricken regions in Africa.

"More work needs to be done but this simple, effective farming practice could be an answer to major global challenges such as developing 'climate smart' agricultural systems which can feed growing populations and adapt to climate change."

Similar soils created by Amazonian people in pre-Columbian eras have recently been discovered in South America - but the techniques people used to create these soils are unknown. Moreover, the activities which led to the creation of these anthropogenic soils were largely disrupted after the European conquest.

Encouragingly researchers in the West Africa study were able to live within communities as they created their fertile soils. This enabled them to learn the techniques used by the women from the indigenous communities who disposed of ash, bones and other organic waste to create the African Dark Earths.

Dr Dawit Solomon, the lead author from Cornell University, said: "What is most surprising is that in both Africa and in Amazonia, these two isolated indigenous communities living far apart in distance and time were able to achieve something that the modern-day agricultural management practices could not achieve until now.

"The discovery of this indigenous climate smart soil-management practice is extremely timely. This valuable strategy to improve soil fertility while also contributing to climate-change mitigation and adaptation in Africa could become an important component of the global climate-smart agricultural management strategy to achieve food security."

The study, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, entitled "Indigenous African soil enrichment as a climate-smart sustainable agriculture alternative", has been published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Environment.

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/summer-2016/article/700-year-old-west-african-soil-technique-could-help-mitigate-climate-change

|

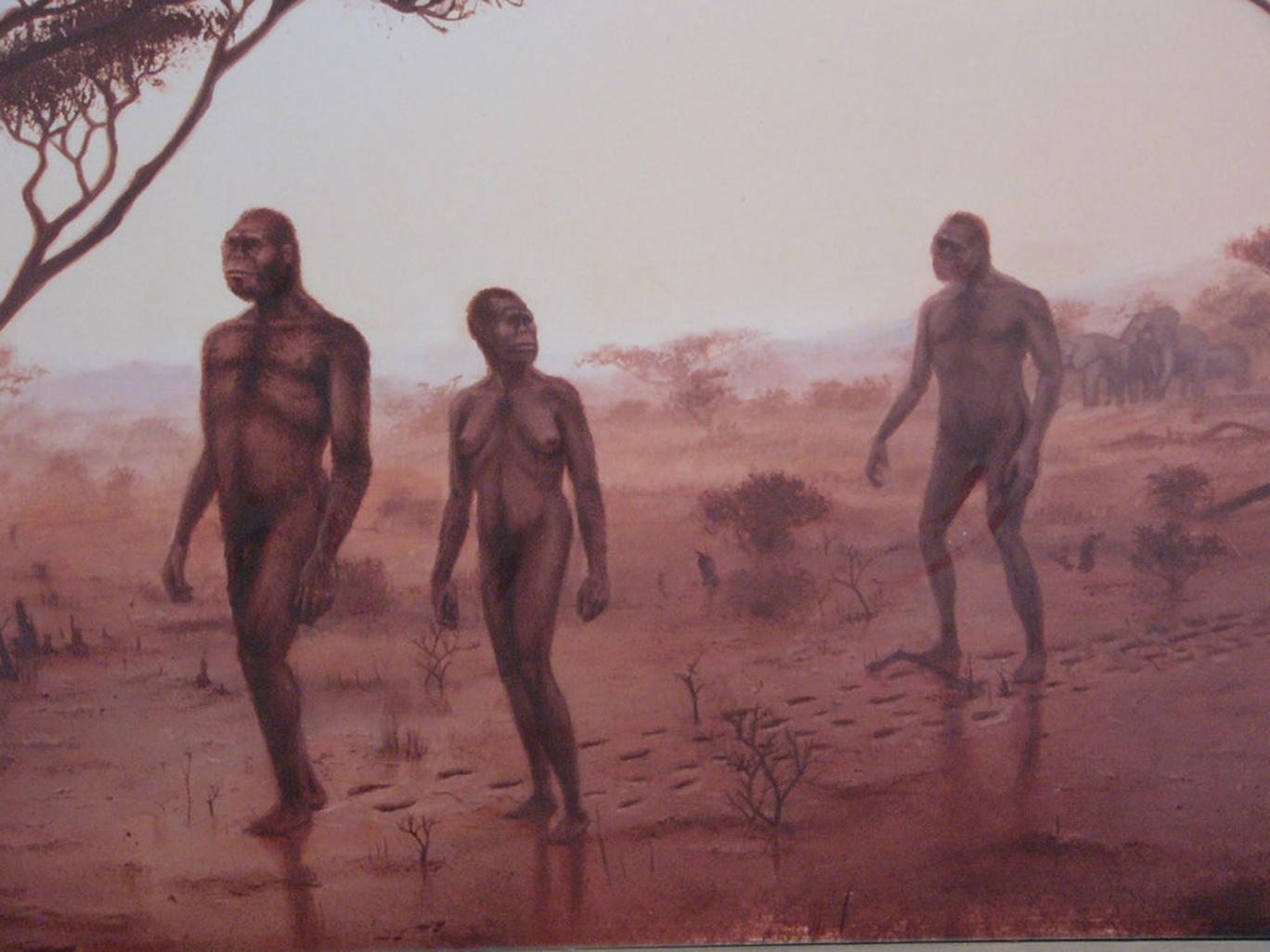

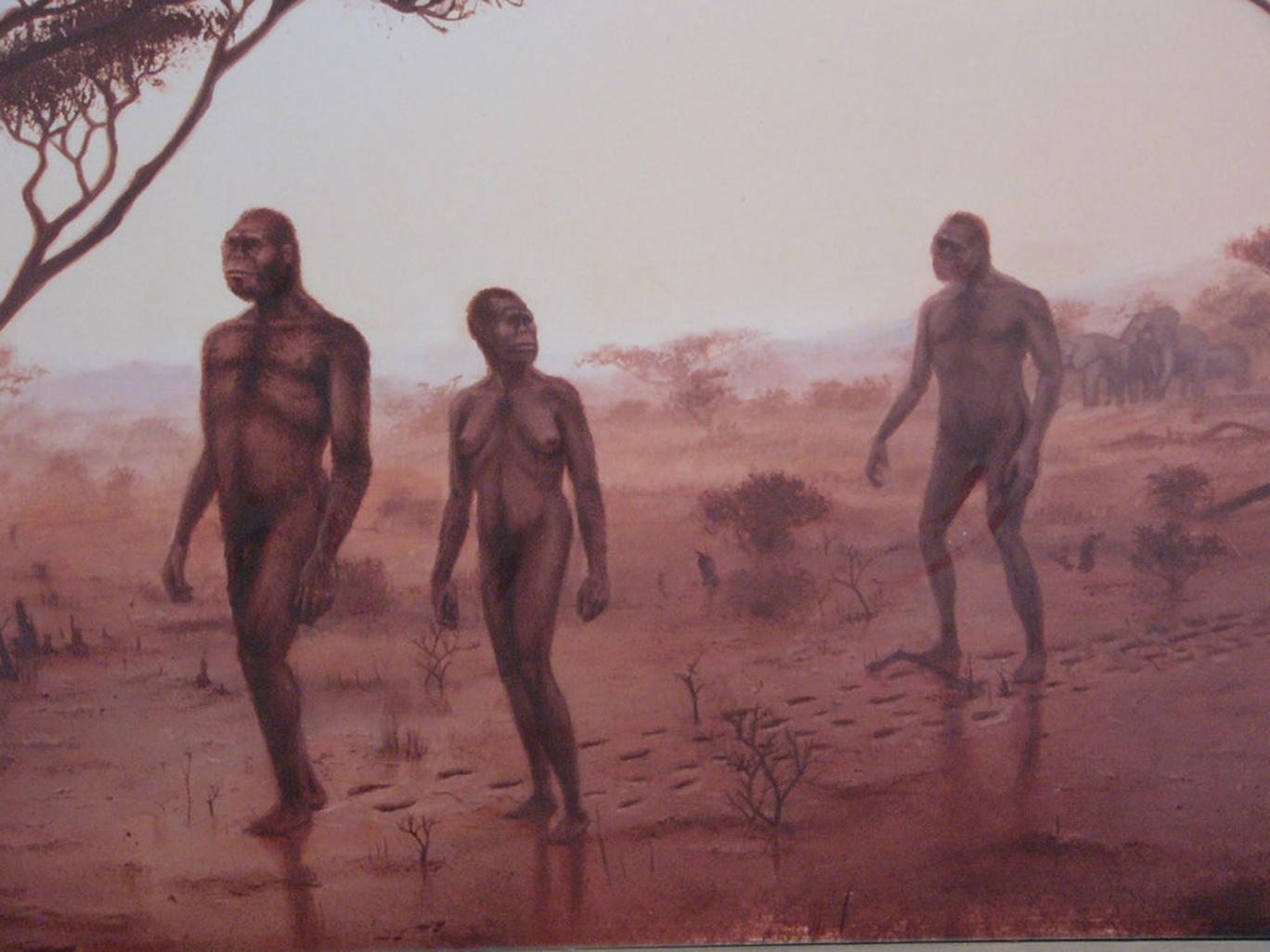

Donald Johanson of the Institute of Human Origins, Arizona State Univeristy, first discovered fossils of Australopithecus afarensis, the individual remains of which are famously known as 'Lucy', in Ethiopia in 1974.

|

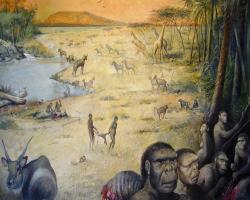

Lucy had neighbors: A review of African fossils

7 June 2016

If "Lucy" wasn't alone, who else was in her neighborhood? Key fossil discoveries over the last few decades in Africa indicate that multiple early human ancestor species lived at the same time more than 3 million years ago. A new review of fossil evidence from the last few decades examines four identified hominin species that co-existed between 3.8 and 3.3 million years ago during the middle Pliocene. A team of scientists compiled an overview that outlines a diverse evolutionary past and raises new questions about how ancient species shared the landscape.

The perspective paper, "The Pliocene hominin diversity conundrum: Do more fossils mean less clarity?" will be published June 6, 2016 as part of a Human Origins Special Feature in the Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Authors Dr. Yohannes Haile-Selassie and Dr. Denise Su of The Cleveland Museum of Natural History and Dr. Stephanie Melillo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany provide an up-to-date review of middle Pliocene hominin fossils found in Ethiopia, Kenya and Chad. The researchers trace the fossil record, which illustrates a timeline placing multiple species overlapping in time and geographic space. Their insights spur further questions about how these early human ancestors were related and shared resources.

"It is now obvious that more than one species of early hominin co-existed during Lucy's time," said lead author Dr. Yohannes Haile-Selassie, curator of physical anthropology at The Cleveland Museum of Natural History. "The question now is not whether Australopithecus afarensis, the species to which the famous Lucy belongs, was the only potential human ancestor species that roamed in what is now the Afar region of Ethiopia during the middle Pliocene, but how these species are related to each other and exploited available resources."

The 1974 discovery of Australopithecus afarensis, which lived from 3.8 to 2.9 million years ago, was a major milestone in paleoanthropology that pushed the record of hominins earlier than 3 million years ago and demonstrated the antiquity of human-like walking. Scientists have long argued that there was only one pre-human species at any given time before 3 million years ago that gave rise to another new species through time in a linear manner. This was what the fossil record appeared to indicate until the end of the 20th century. The discovery of Australopithecus bahrelghazali from Chad in 1995 and Kenyanthropus platyops from Kenya in 2001 challenged this idea. However, these two species were not widely accepted, rather considered as geographic variants of Lucy's species, Australopithecus afarensis. The discovery of the 3.4 million-year-old Burtele partial foot from the Woranso-Mille announced by Haile-Selassie in 2012 was the first conclusive evidence that another early human ancestor species lived alongside Australopithecus afarensis. In 2015, fossils recovered from Haile-Selassie's ongoing research site at the Woranso-Mille area of the Afar region of Ethiopia were assigned to the new species Australopithecus deyiremeda. However, the Burtele partial foot was not included in this species.

"The Woranso-Mille paleontological study area in Ethiopia's Afar region reveals that there were at least two, if not three, early human species living at the same time and in close geographic proximity," said Haile-Selassie. "This key research site has yielded new and unexpected evidence indicating that there were multiple species with different locomotor and dietary adaptations. For nearly four decades, Australopithecus afarensis was the only known species—but recent discoveries are opening a new window into our evolutionary past."

Co-author Dr. Denise Su, curator of paleobotany and paleoecology at The Cleveland Museum of Natural History, reconstructs ancient ecosystems. "These new fossil discoveries from Woranso-Mille are bringing forth avenues of research that we have not considered before," said Su. "How did multiple closely related species manage to co-exist in a relatively small area? How did they partition the available resources? These new discoveries keep expanding our knowledge and, at the same time, raise more questions about human origins."

Paleoanthropologists face the challenges and debates that arise from small sample sizes, poorly preserved prehistoric specimens and lack of evidence for ecological diversity. Questions remain about the relationships of middle Pliocene hominins and what adaptive strategies might have allowed for the coexistence of multiple, closely related species.

"We continue to search for more fossils," said Dr. Stephanie Melillo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany. "We know a lot about the skeleton of A. afarensis, but for the other middle Pliocene species, most of the anatomy remains unknown. Ultimately, larger sample sizes will be the key to sorting out which species are present and how they are related. This makes every fossil discovery all the more exciting."

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/spring-2016/article/lucy-had-neighbors-a-review-of-african-fossils

|

The fossils of Homo naledi. Courtesy John Hawks, Wits University

|

Space-age exploration for prehistoric bones in South Africa

30 May 2016

In 2013, after the discovery of an unprecedented hominin assemblage in South Africa, the University of the Witwatersrand's (Wits) Professor Lee Berger extended a worldwide call for "skinny" explorers to join him on the expedition to excavate what became known as the Dinaledi Chamber, located within a cave system known as Rising Star near the Sterkfontein Caves, about 40km North West of Johannesburg. An all-female team of six "underground astronauts" were selected to undertake the underground excavation, due to the challenge of navigating a 12-meter vertical chute and passing through an 18-centimeter gap. Over 1500 fossils were found, representing a new species designated by the examining scientists as Homo naledi.

Berger himself was unable to go down into the chamber, and the extremely difficult conditions in which Berger's Rising Star team was forced to work thus gave rise to the use of space-age technology to bring the high resolution digital images to Berger and team members on an almost real-time basis in order to make vital decisions regarding the underground excavations. Ashley Kruger, a PhD candidate in Palaeoanthropology at the Evolutionary Studies Institute at Wits, who was part of Berger's initial Rising Star Expedition team, roped in the use of high-tech laser scanning, photogrammetry and 3D mapping technology to make this possible.

"This is the first time ever, where multiple digital data imaging collection has been used on such a sale, during a hominin excavation," says Kruger.

Kruger and colleagues have now mapped the entire path of the Rising Star Cave, including the Dinaledi Chamber, both on the surface and underground, using a combination of aerial drone photography, high-resolution 3D laser scanning, a technique called white-light source photogrammetry, and conventional surveying techniques. The research paper, Multimodal spatial mapping and visualisation of Dinaledi Chamber and Rising Star Cave was published in the scientific journal, the South African Journal of Science, on Friday (see link to the paper below).

"The 3D scans of the cave and excavation area helped scientists above ground immensely in making decisions about the next step to take with regards to excavations," says Dr. Marina Elliot, Rising Star excavation manager, and co-author of the paper.

"These methods provided researchers with a digital representation of the site from landscape level right down to individual bones," says Kruger.

The precise digital reconstruction of the Rising Star Cave provides new insights into the Dinaledi Chamber's structure and location, as well as the exact location of the fossil site. It also paints a detailed picture of the challenges that the underground astronauts had to deal with in navigating the caves on a daily basis for over five weeks in November 2013 and March 2014.

"We realise now, through the use of high-resolution scanning that the Dinaledi chamber is about 10 meters deeper than we originally thought," says Kruger. This is important in understanding the processes which may have aided the site's formation.

Kruger's paper is the first of a number of papers due to be published on the spatial understanding of the Homo naledi site within the Dinaledi chamber. The rest of his research aims to provide answers about how the site formed, what the position of the fossils can tell researchers, as well as to paint a more detailed picture on how the hominin bodies came to be in the cave.

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/spring-2016/article/space-age-exploration-for-prehistoric-bones-in-south-africa

|

|

Migration back to Africa took place during the Paleolithic

26 May 2016

A piece of international research led by the UPV/EHU-University of the Basque Country has retrieved the mitogenome of a fossil belonging to the first Homo sapiens population in Europe.

A palaeogenomics study conducted by the Human Evolutionary Biology group of the Faculty of Science and Technology, led by Concepción de la Rua, in collaboration with researchers in Sweden, the Netherlands and Romania, has made it possible to retrieve the complete sequence of the mitogenome of the Pestera Muierii woman (PM1) using two teeth. This mitochondrial genome corresponds to the now disappeared U6 basal lineage, and it is from this lineage that the U6 lineages, now existing mainly in the populations of the north of Africa, descend from.

The study has not only made it possible to confirm the Eurasian origin of the U6 lineage but also to support the hypothesis that some populations embarked on a back-migration to Africa from Eurasia at the start of the Upper Palaeolithic, about 40-45,000 years ago. The Pestera Muierii individual represents one branch of this return journey to Africa of which there is no direct evidence owing to the lack of Palaeolithic fossil remains in the north of Africa.

"Right now, the research group is analysing the nuclear genome, the results of which could provide us with information about its relationship with the Neanderthals and about the existence of genomic variations associated with the immune system that accounts for the evolutionary success of Homo sapiens over other human species with whom it co-existed. What is more, we will be able to see what the phenotypic features of early Homo sapiens were like, and also see how population movements in the past influence the understanding of our evolutionary history," explained Prof Concepción de la Rúa.

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/spring-2016/article/migration-back-to-africa-took-place-during-the-paleolithic

|

Interior of the Church

of Archangel Raphael

in Dongola. Photo by

M. Reklajtis, archives

of the Centre of Mediterranean

Archaeology,

University of

Warsaw

|

Polish archaeologists discovered dozens of paintings in Sudan

19 May 2016

The largest group of paintings from the turn of the VIII/IX century has been discovered in Sudan by the mission of the Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw.

The discovery was made during excavations inside the Church of Raphael in the royal complex in Dongola, northern Sudan. The temple is located next to the relics of a medieval palace. Dongola was the capital of Makuria, a powerful kingdom, which existed from the sixth to the fourteenth century, between I and V cataracts of the Nile. Its power is evidenced by the fact that the army of Makuria stopped the pressure of Muslim army in the first half of the VII century.

The church was discovered in 2006. However, it was crucial for the researchers to secure the structure. It was not until last year that a roof was built, which allowed to begin excavations.

"The design is unique - it does not repeat the plans of other famous religious buildings of this type. Paintings are also unusual" - told PAP Prof. Wlodzimierz Godlewski from the Institute of Archaeology of the University of Warsaw, a longtime researcher of Dongola.

The paintings depict images of archangels, angels, priests, saints and Nubian kingdom officials from the beginning of the IX century. Originally, at each of the figures was a "legend" describing each person and their function.

Prof. Godlewski drew attention to one of the inscriptions discovered on the wall of the baptistery, which in his opinion has great historical significance. "The inscription commemorates the meeting of the bishops of Makuria with the king and archbishop of Dongola that took place in this church. This record revealed the territorial division of the church in Makuria - it listed the names of the bishops from particular towns" - said Prof. Godlewski. The meeting was presided over by the king - also named in the inscription - who was formally the head of the church in this state. An interesting fact is that the meeting was attended by - endowed with the title of Metropolitan - bishop of Faras, where decades ago the Poles led by Prof. Kazimierz Michalowski discovered a cathedral with paintings, some of which can be admired today in the National Museum in Warsaw.

"The church was founded by King Joannes. Until now we did not know much about him. The inscription proves that he was an important person in the hierarchy of the church and had considerable political influence" - added the scientist.

In the Church of Raphael archaeologists also discovered the earliest known in Makuria image of the king made in the church - in this case, in the apse.

"It is the oldest example of the official iconography introduced into the sacred interior - we know a similar example from Faras, but it comes from a later period" - added Prof. Godlewski.

The scientist believes that in terms of technology the paintings from the Church of Raphael are superior to those from Faras. They were made on a smooth lime plaster. The artists also used a number of expensive pigments, among others, of blue colour - lapis lazuli, rock outcrops of which are very far away from today's Sudan.

Among the interesting discoveries scientist also mentions a pulpit made of granite blocks brought from a pharaonic temple. Hieroglyphic inscriptions are visible on one of the blocks.

Another important find is a fragment of an icon made on wood. "This is the first such object discovered in the history of Sudan" - says the researcher. The icon is double-sided. On one side there is the image of the Virgin with a prayer, and on the other - a historical figure, possibly a local ruler. The object comes from the golden age of the kingdom of Makuria, the VIII-XI century.

The study took place in February. It will continue in November, provided that the researchers have sufficient funds.

Source: http://scienceinpoland.pap.pl/en/news/news,409710,polish-archaeologists-discovered-dozens-of-paintings-in-sudan.html

|

Michele Buzon, a

Purdue University

associate professor of anthropology, is excavating pyramid

tombs in Tombos,

Sudan to study

Egyptian and Nubian cultures from

thousands of years ago in the Nile River Valley

|

Burial sites show how Nubians, Egyptians integrated communities thousands of years ago

18 May 2016

New bioarchaeological evidence shows that Nubians and Egyptians integrated into a community, and even married, in ancient Sudan, according to new research from a Purdue University anthropologist.

"There are not many archaeological sites that date to this time period, so we have not known what people were doing or what happened to these communities when the Egyptians withdrew," said Michele Buzon, an associate professor of anthropology, who is excavating Nubian burial sites in the Nile River Valley to better understand the relationship between Nubians and Egyptians during the New Kingdom Empire.

The findings are published in American Anthropologist, and this work has been funded by the National Science Foundation and the National Geographic Society's Committee for Research and Exploration. Buzon also collaborated with Stuart Tyson Smith from the University of California, Santa Barbara, on this UCSB-Purdue led project. Antonio Simonetti from the University of Notre Dame also is a study co-author.

Egyptians colonized the area in 1500 BCE to gain access to trade routes on the Nile River. This is known as the New Kingdom Empire, and most research focuses on the Egyptians and their legacy.

"It's been presumed that Nubians absorbed Egyptian cultural features because they had to, but we found cultural entanglement ? that there was a new identity that combined aspects of their Nubian and Egyptian heritages. And based on biological and isotopic features, we believe they were interacting, intermarrying and eventually becoming a community of Egyptians and Nubians," said Buzon, who just returned from the excavation site.

During the New Kingdom Period, from about 1400-1050 BCE, Egyptians ruled Tombos in the Nile River Valley's Nubian Desert in the far north of Sudan. In about 1050 BCE, the Egyptians lost power during the Third Intermediate Period. At the end of this period, Nubia gained power again and defeated Egypt to rule as the 25th dynasty.

"We now have a sense of what happened when the New Kingdom Empire fell apart, and while there had been assumptions that Nubia didn't function very well without the Egyptian administration, the evidence from our site says otherwise," said Buzon, who has been working at this site since 2000, focusing on the burial features and skeletal health analysis. "We found that Tombos continued to be a prosperous community. We have the continuation of an Egyptian Nubian community that is successful even when Egypt is playing no political role there anymore."

Human remains and burial practices from 24 units were analyzed for this study.

The tombs, known as tumulus graves, show how the cultures merged. The tombs' physical structure, which are mounded, round graves with stones and a shaft underneath, reflect Nubian culture.

"They are Nubian in superstructure, but inside the tombs reflect Egyptian cultural features, such as the way the body is positioned," Buzon said. "Egyptians are buried in an extended position; on their back with their arms and legs extended. Nubians are generally on their side with their arms and legs flexed. We found some that combine a mixture of traditions. For instance, bodies were placed on a wooden bed, a Nubian tradition, and then placed in an Egyptian pose in an Egyptian coffin."

Skeletal markers also supported that the two cultures merged.

"This community developed over a few hundred years and people living there were the descendants of that community that started with Egyptian immigrants and local Nubians," Buzon said. "They weren't living separately at same site, but living together in the community."

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/spring-2016/article/burial-sites-show-how-nubians-egyptians-integrated-communities-thousands-of-years-ago

|

|

Researchers prove humans in Southern Arabia 10,000 years earlier than first thought

11 May 2016

THE last Ice Age made much of the globe uninhabitable, but there were oases - or refugia - where people 20,000 years ago were able to cluster and survive. Researchers at the University of Huddersfield, who specialise in the analysis of human DNA, have found new evidence that there was one or more of these shelters in what is now Southern Arabia.

Once the Ice Age receded - with the onset of the Late Glacial period about 15,000 years ago - the people of this refugium then dispersed and populated Arabia and the Horn of Africa, and might also have migrated further afield.

The view used to be that people did not settle in large numbers in Arabia until the development of agriculture, around 10-11,000 years ago. Now, the findings by members of the University of Huddersfield's Archaeogenetics Research Group demonstrate that modern humans have dwelt in this territory for far longer than previously thought. The new genetic data and analysis bolsters a theory that has long been held by archaeologists, although they had little evidence to support it until now.

The new argument for an Ice Age refugium in Arabia - perhaps on the Red Sea plains - is put forward in a new article published in the journal Scientific Reports. Its principal author is Dr Francesca Gandini, who was based at the University of Pavia in Italy before relocating in early 2015 to the University of Huddersfield, where she is a Research Fellow in Archaeogenetics and a member of the group headed by Professor Martin Richards.

Dr Gandini is currently playing a central role in the development of an Ancient DNA lab at the University of Huddersfield, which is home to a Centre for Evolutionary Genomics. It has been awarded 1 million GBP by the Leverhulme Trust in order to provide doctoral training to the next generations of specialists in a field that uses the latest DNA science to delve into evolutionary history.

The new discoveries about an Ice Age refugium in Arabia and the subsequent outward migration are based on a study of a rare mitochondrial DNA lineage named R0a, which, uniquely, is most frequent in Arabia and the Horn of Africa. Dr Gandini and her co-researchers have reached the conclusion that this lineage is more ancient than previously thought and that it has a deeper presence in Arabia than was earlier believed. This makes the case for at least one glacial refugium during the Pleistocene period, which spanned the Ice Age.

The new article also describes the dispersals during the postglacial period, around 11,000 years ago, of people from Arabia into eastern Africa. Moreover, there is evidence for the movement of people in the R0a haplogroup through the Middle East and into Europe and there might also have been a trading network and a "gene flow" from Arabia into the territories that are now Iran, Pakistan and India.

Source: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2016-05/uoh-rph051116.php

|

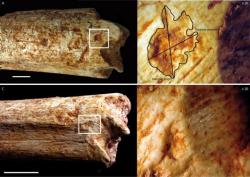

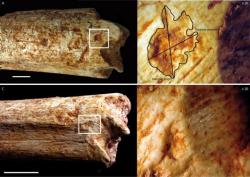

Tooth-marks on Pleistocene Moroccan femur indicate hominin hunting or scavenging

by large carnivores.

|

Hominins may have been food for carnivores 500,000 years ago

27 April 2016

Tooth-marks on a 500,000-year-old hominin femur bone found in a Moroccan cave indicate that it was consumed by large carnivores, likely hyenas, according to a study published April 27, 2016 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Camille Daujeard from the Muséum National D'Histoire Naturelle, France, and colleagues.

During the Middle Pleistocene, early humans likely competed for space and resources with large carnivores, who occupied many of the same areas. However, to date, little evidence for direct interaction between them in this period has been found. The authors of the present study examined the shaft of a femur from the skeleton of a 500,000-year-old hominin, found in the Moroccan cave "Grotte à Hominidés" cave near Casablanca, Morocco, and found evidence of consumption by large carnivores.

The authors' examination of the bone fragment revealed various fractures and tooth marks indicative of carnivore chewing, including tooth pits as well as other scores and notches. These were clustered at the two ends of the femur, the softer parts of the bone being completely crushed. The marks were covered with sediment, suggesting that they were very old.

While the appearance of the marks indicated that they were most likely made by hyenas shortly after death, it was not possible to conclude whether the bone had been eaten as a result of predation on the hominin or had been scavenged soon after death. Nonetheless, this is the first evidence that humans were a resource for carnivores during the Middle Pleistocene in this part of Morocco, and contrasts with evidence from nearby sites that humans themselves hunted and ate carnivores. The authors suggest that depending on circumstances, hominins at this time could have both acted as hunter or scavenger, and been targeted as carrion or prey.

Camille Daujeard notes: "Although encounters and confrontations between archaic humans and large predators of this time period in North Africa must have been common, the discovery ... is one of the few examples where hominin consumption by carnivores is proven."

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/spring-2016/article/hominins-may-have-been-food-for-carnivores-500-000-years-ago

|

Previous analysis

showed evidence

of just three individuals walking across that

tephra-covered land

almost 3.7 million

years ago

|

One small step, one giant stride in our understanding of our ancestors as scientists analyse prehistoric footprints

25 April 2016

Prehistoric ape-men, living some three and a half million years before the first anatomically modern humans, walked like us - according to remarkable new research, carried out at a UK university.

The discovery has substantial implications for more fully understanding key aspects of subsequent early human evolution - and means that some very early human ancestors may have been more like us in some respects than has often been thought.