This handaxe weighs almost 8 pounds and is unusually heavy. It and many of the other stone artifacts at Wadi Dabsa date to some point between 1.76 million years ago and 100,000 years ago. Researchers are trying to determine a more precise date. Credit: Andrew Shuttleworth and Frederick Foulds

|

Ancient Axes, Spear Points May Reveal When Early Humans Left Africa

27 December 2017

More than 1,000 stone artifacts, some of which may be up to 1.76 million years old, have been discovered at Wadi Dabsa, in southwest Saudi Arabia near the Red Sea.

The artifacts, which were found in what is now an arid landscape, date to a time when the climate was wetter; they may provide clues as to how and when different hominins left Africa, researchers said.

The stone artifacts include the remains of hand axes, cleavers (a type of knife), scrapers (used to scrape the flesh off of animal hides), projectile points (that would have been attached to the ends of spears), piercers (stone tools that can cut small holes through hide or flesh) and hammer stones. One of the hand axes is unusually heavy, weighing just under 8 lbs. (3.6 kilograms), the researchers said. The discoveries were detailed in the December 2017 issue of the journal Antiquity. [The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

Based on the tool design, archaeologists said they can tell that many of the artifacts are "Acheulian," a term used to describe types of stone tools made between 1.76 million years and 100,000 years ago. When exactly within this time frame the various artifacts at Wadi Dabsa were made is uncertain, the archaeologists said.

"We hope to try and date the tufa [a type of limestone] and basalt flows within the site, which are associated [with] the large [stone artifact] assemblage recovered from within the wadi," said study lead author Frederick Foulds, an archaeology professor at Durham University in England. Once the team has more-precise dates for the artifacts, the scientists may be able to determine what type of hominins made the tools, Foulds said.

A wetter time

Archaeologists said they can already tell that the artifacts date to a time when the climate was wetter. "It's far more arid [today] than it was at certain points in time," Foulds told Live Science. "It's strange to be walking over hard, dry rocks which were formed by water pooling during a far wetter period. We think it was during these wetter periods that it's likely the site was occupied."

The climate of the entire Arabian Peninsula has changed multiple times in response to the massive changes in global climates that accompanied glacial cycles over the last 2.5 million years, Foulds said.

"During periods when the ice sheets were at their largest, there was widespread aridity in the Sahara and Arabian deserts, but during periods when the ice sheets shrank, the climate of these regions became a lot wetter," Foulds said.

One of the big questions is how the changes in climate affected the dispersal of hominins from out of Africa, Foulds said.

"What's interesting about the Wadi Dabsa region is that the geography of the region may have created a refuge from these changes," Foulds said.

Because of Wadi Dabsa's topography the region may have received rainfall when other parts of Saudi Arabia were arid. Hominins were able "to continue living there [at Wadi Dabsa] when they couldn't live in other areas," Foulds said. Researchers have found that Wadi Dabsa's topography includes a basin which may have had streams of water flowing down its slopes, the water possibly pooling in the basin.

The team is carrying out its research as part of the DISPERSE project, which is analyzing landscape and archaeological changes in Africa and Asia in order to better understand how humans evolved and dispersed out of Africa.

Source: https://www.livescience.com/61285-stone-tools-found-in-saudi-arabia.html

|

The astrolabe has the Portuguese royal coat of arms (top) and an

armillary sphere (bottom), which is the personal emblem of Dom Manuel I. Photograph by David Mearns, National Geographic Creative

|

Rare Solar Navigation Tool Found in Ancient Shipwreck

24 October 2017

When a small, 500-year-old copper disk was discovered among the remains of a shipwreck off the coast of Oman in 2014, archaeologists suspected it was a navigation tool called an astrolabe.

Now, thanks to 3D scanning technology, scientists are able to see the small faded measurements etched into the disk - which confirm that it is in fact an astrolabe. It is also now thought to be the earliest such find from a period known as the European Age of Exploration.

The disk was found on a ship called the Esmeralda, which belonged to a fleet led by the famous Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama during his search for a route from Europe to India in 1502-1503.

In 2014, a team of excavators led by marine scientist David L. Mearns and his company Bluewater Discoveries Ltd. loosened the astrolabe from sand covering hundreds of other relics that sat on the sea floor. In an interim report they published last year on the find in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, they theorized that the disk was used for navigation.

A Portuguese royal coat of arms was visible on the disk's top half, and on the bottom was an etching of an armillary sphere, which Mearns claimed belonged to Portuguese King Dom Miguel. These etchings indicated to archeologists that the object was a "high-status" object aboard the Esmeralda.

While these markings suggested that the disk was used for navigation, Mearns and his team needed more proof before they could declare it with certainty.

That's where Mark Williams, a professor at the University of Warwick, and a team of engineers came in. They flew to Oman to scan and render 3D images of the 500-year-old artifact. Using a laser scanner that produces 80,000 measurement points per second, they were able to create a 3D model of the astrolabe.

What they saw on the scans wasn't visible to the naked eye - eighteen individual lines emerging from a hole in the center of the disk and arranged at five-degree increments.

"The markings were very fine and, due to damage to the surface, almost invisible to the human eye," said Williams. "The resolution of the 3D data allowed us to zoom in and identify the marks and subsequently characterize them."

Markings on astrolabes are used to measure angles. They're one of human civilization's most advanced ancient tools and are thought to have become popular just prior to the current era. By aligning an astrolabe perpendicular to the horizon, ancient astronomers could calculate measurements like time and position.

Astrolabes used by early sea explorers are frequently referred to as mariner's astrolabes. A broken bracket at the top of the disc indicates it was likely suspended to align it perpendicularly to the horizon. By measuring the altitude of the sun at noon, navigators could then measure the sun's declination, which accurately told sailors their latitude.

An Age of Discovery

The 15th century to the 17th century marked a period of booming European exploration, during which time European nations were fervently searching for maritime routes.

When da Gama embarked on his second voyage to India, around 1502-1503, he took with him a fleet of 20 ships, including the Esmeralda. European interest in Indian spices burgeoned during the 15th century, but passage to India was largely controlled by Arab rulers. da Gama become the first to chart a nautical path directly to India by sailing around the horn of Africa.

Stories passed down from witnesses and damage on part of the ship's remains indicate it probably sank from a storm that smashed it into deadly rocks. The remains were initially located in 1998, but it wasn't until 2013 that Mearns - supported in part by the National Geographic Society Expeditions Council - unearthed thousands of the ship's treasures.

"We really don't know much about early astrolabes, so this one is precious from that viewpoint," said Luis Filipe Viera de Castro, a professor of nautical archaeology at Texas A&M University. Previously, the earliest known example of a mariner's astrolabe was dated to a 1554 Spanish shipwreck that sank near the coast of south Texas.

"It is also precious because it almost certainly comes from one of Vicente Sodré's lost ships, and these were probably the first European warships to enter the Indian Ocean," said Castro.

Vicente Sodré was da Gama's maternal uncle and commander of the Esmeralda. Cannonballs bearing his initials were found among the watery wreckage. Instructed by da Gama to guard Portuguese factories off the coast of India, the Sodré brothers instead sailed to the Gulf of Aden, where they looted Arab ships. Both Vicente and his brother Brás died when the ships sank during a storm.

Source: https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/10/navigation-tool-astrolabe-vasco-da-gama-shipwreck-esmeralda-spd/

|

The Lamont-Doherty Core Repository contains one

of the world's most unique and important collection of scientific samples from the deep sea. Sediment cores from every major ocean

and sea are archived here. The repository provides

for long-term curation and archiving of samples and cores to ensure their preservation and

usefulness to current and future generations of scientists.

Credit: Courtesy Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

|

Ancient humans left Africa to escape drying climate

5 October 2017

Humans migrated out of Africa as the climate shifted from wet to very dry about 60,000 years ago, according to research led by a University of Arizona geoscientist.

Genetic research indicates people migrated from Africa into Eurasia between 70,000 and 55,000 years ago. Previous researchers suggested the climate must have been wetter than it is now for people to migrate to Eurasia by crossing the Horn of Africa and the Middle East.

"There's always been a question about whether climate change had any influence on when our species left Africa," said Jessica Tierney, UA associate professor of geosciences. "Our data suggest that when most of our species left Africa, it was dry and not wet in northeast Africa."

Tierney and her colleagues found that around 70,000 years ago, climate in the Horn of Africa shifted from a wet phase called "Green Sahara" to even drier than the region is now. The region also became colder.

The researchers traced the Horn of Africa's climate 200,000 years into the past by analyzing a core of ocean sediment taken in the western end of the Gulf of Aden. Tierney said before this research there was no record of the climate of northeast Africa back to the time of human migration out of Africa.

"Our data say the migration comes after a big environmental change. Perhaps people left because the environment was deteriorating," she said. "There was a big shift to dry and that could have been a motivating force for migration."

"It's interesting to think about how our ancestors interacted with climate," she said.

The team's paper, "A climatic context for the out-of-Africa migration," is published online in Geology this week. Tierney's co-authors are Peter deMenocal of the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, New York, and Paul Zander of the UA.

The National Science Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation funded the research.

Tierney and her colleagues had successfully revealed the Horn of Africa's climate back to 40,000 years ago by studying cores of marine sediment. The team hoped to use the same means to reconstruct the region's climate back to the time 55,000 to 70,000 years ago when our ancestors left Africa.

The first challenge was finding a core from that region with sediments that old. The researchers enlisted the help of the curators of the Lamont-Doherty Core Repository, which has sediment cores from every major ocean and sea. The curators found a core collected off the Horn of Africa in 1965 from the R/V Robert D. Conrad that might be suitable.

Co-author deMenocal studied and dated the layers of the 1965 core and found it had sediments going back as far as 200,000 years.

At the UA, Tierney and Paul Zander teased out temperature and rainfall records from the organic matter preserved in the sediment layers. The scientists took samples from the core about every four inches (10 cm), a distance that represented about every 1,600 years.

To construct a long-term temperature record for the Horn of Africa, the researchers analyzed the sediment layers for chemicals called alkenones made by a particular kind of marine algae. The algae change the composition of the alkenones depending on the water temperature. The ratio of the different alkenones indicates the sea surface temperature when the algae were alive and also reflects regional temperatures, Tierney said.

To figure out the region's ancient rainfall patterns from the sediment core, the researchers analyzed the ancient leaf wax that had blown into the ocean from terrestrial plants. Because plants alter the chemical composition of the wax on their leaves depending on how dry or wet the climate is, the leaf wax from the sediment core's layers provides a record of past fluctuations in rainfall.

The analyses showed that the time people migrated out of Africa coincided with a big shift to a much drier and colder climate, Tierney said.

The team's findings are corroborated by research from other investigators who reconstructed past regional climate by using data gathered from a cave formation in Israel and a sediment core from the eastern Mediterranean. Those findings suggest that it was dry everywhere in northeast Africa, she said.

"Our main point is kind of simple," Tierney said. "We think it was dry when people left Africa and went on to other parts of the world, and that the transition from a Green Sahara to dry was a motivating force for people to leave."

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/fall-2017/article/ancient-humans-left-africa-to-escape-drying-climate

|

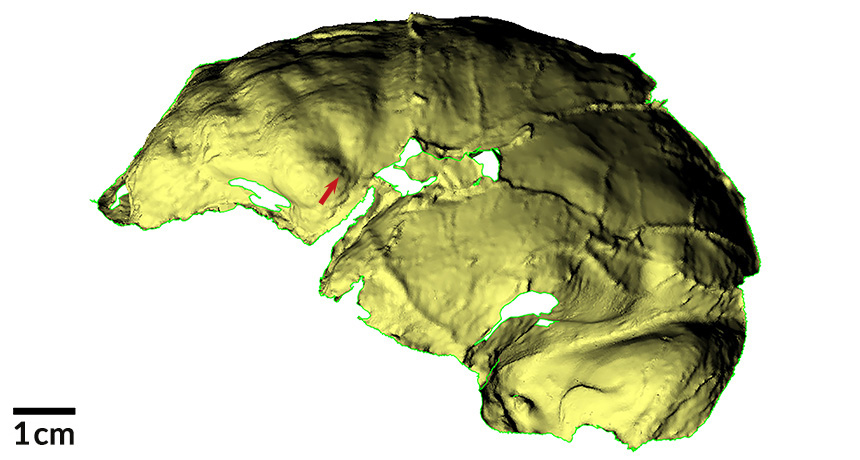

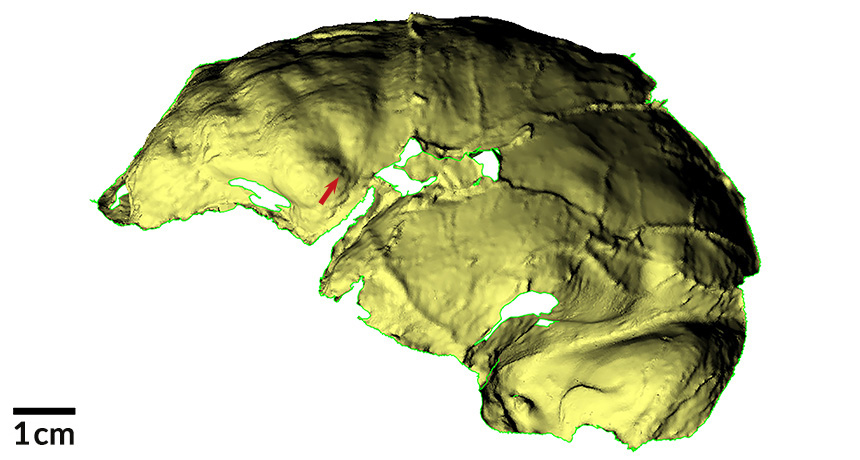

A cast of a P. boisei skull, used for teaching at Cambridge University. Credit: Louise Walsh

|

Meet the hominin species that gave us genital herpes

3 October 2017

Two herpes simplex viruses infect primates from unknown evolutionary depths. In modern humans these viruses manifest as cold sores (HSV1) and genital herpes (HSV2).

Unlike HSV1, however, the earliest proto-humans did not take HSV2 with them when our ancient lineage split from chimpanzee precursors around 7 million years ago. Humanity dodged the genital herpes bullet - almost.

Somewhere between 3 and 1.4 million years ago, HSV2 jumped the species barrier from African apes back into human ancestors - probably through an intermediate hominin species unrelated to humans. Hominin is the zoological 'tribe' to which our species belongs.

Now, a team of scientists from Cambridge and Oxford Brookes universities believe they may have identified the culprit: Paranthropus boisei, a heavyset bipedal hominin with a smallish brain and dish-like face.

In a study published today in the journal Virus Evolution, they suggest that P. boisei most likely contracted HSV2 through scavenging ancestral chimp meat where savannah met forest - the infection seeping in via bites or open sores.

Hominins with HSV1 may have been initially protected from HSV2, which also occupied the mouth. That is until HSV2 "adapted to a different mucosal niche" say the scientists. A niche located in the genitals.

Close contact between P. boisei and our ancestor Homo erectus would have been fairly common around sources of water, such as Kenya's Lake Turkana. This provided the opportunity for HSV2 to boomerang into our bloodline.

The appearance of Homo erectus around 2 million years ago was accompanied by evidence of hunting and butchery. Once again, consuming "infected material" would have transmitted the virus - only this time it was P. boisei being devoured.

"Herpes infect everything from humans to coral, with each species having its own specific set of viruses," said senior author Dr Charlotte Houldcroft, a virologist from Cambridge's Department of Archaeology.

"For these viruses to jump species barriers they need a lucky genetic mutation combined with significant fluid exchange. In the case of early hominins, this means through consumption or intercourse - or possibly both."

"By modelling the available data, from fossil records to viral genetics, we believe that Paranthropus boisei was the species in the right place at the right time to both contract HSV2 from ancestral chimpanzees, and transmit it to our earliest ancestors, probably Homo erectus."

When researchers from University of California, San Diego, published findings suggesting HSV2 had jumped between hominin species, Houldcroft became curious.

While discussing genital herpes over dinner at Kings College, Cambridge, with fellow academic Dr Krishna Kumar, an idea formed. Kumar, an engineer who uses Bayesian network modelling to predict city-scale infrastructure requirements, suggested applying his techniques to the question of ancient HSV2.

Houldcroft and her collaborator Dr Simon Underdown, a human evolution researcher from Oxford Brookes, collated data ranging from fossil finds to herpes DNA and ancient African climates. Using Kumar's model, the team generated HSV2 transmission probabilities for the mosaic of hominin species that roamed Africa during "deep time".

"Climate fluctuations over millennia caused forests and lakes to expand and contract," said Underdown. "Layering climate data with fossil locations helped us determine the species most likely to come into contact with ancestral chimpanzees in the forests, as well as other hominins at water sources."

Some promising leads turned out to be dead ends. Australopithecus afarensis had the highest probability of proximity to ancestral chimps, but geography also ruled it out of transmitting to human ancestors.

Ultimately, the researchers discovered the key player in all the scenarios with higher probabilities to be Paranthropus boisei. A genetic fit virally who was found in the right places to be the herpes intermediary, with Homo erectus - and eventually us - the unfortunate recipients.

"Once HSV2 gains entry to a species it stays, easily transferred from mother to baby, as well as through blood, saliva and sex," said Houldcroft.

"HSV2 is ideally suited to low density populations. The genital herpes virus would have crept across Africa the way it creeps down nerve endings in our sex organs - slowly but surely."

The team believe their methodology can be used to unravel the transmission mysteries of other ancient diseases - such as human pubic lice, also introduced via an intermediate hominin from ancestral gorillas over 3 million years ago.

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/fall-2017/article/meet-the-hominin-species-that-gave-us-genital-herpes

|

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor). Image credit: Pethan, Botanical Gardens, Utrecht University / CC BY-SA 3.0.

|

Earliest Evidence of Domesticated Sorghum Discovered

28 September 2017

Sorghum was domesticated from its wild ancestor more than 5,000 years ago, according to archaeological evidence uncovered by University College London archaeologist Dorian Fuller and colleagues in Sudan.

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) is a native African grass that was utilized for thousands of years by prehistoric peoples, and emerged as one of the world's five most important cereal crops, along with rice, wheat, barley, and maize.

For a half century scientists have hypothesized that native African groups were domesticating sorghum outside the winter rainfall zone of the ancient Egyptian Nile Valley - where wheat and barley cereals were predominant - in the semi-arid tropics of Africa, but no archaeological evidence existed.

The newest evidence comes from an archaeological site near Kassala in eastern Sudan, dating from 3500 to 3000 BC, and is associated with the Butana Group culture.

"This new discovery in eastern Sudan reveals that during the 4th millennium BC, peoples of the Butana Group were intensively cultivating wild stands of sorghum until they began to change the plant genetically into domesticated morphotypes," Dr. Fuller and co-authors said.

The researchers examined plant impressions within broken pottery from the largest Butana Group site, KG23.

"Ceramic sherds recovered from excavations undertaken by the Southern Methodist University Butana Project during the 1980s from the KG23 site were analyzed," they explained.

"Examination of the plant impressions in the pottery revealed diagnostic chaff in which both domesticated and wild sorghum types were identified, thus providing archaeobotanical evidence for the beginnings of cultivation and emergence of domesticated characteristics within sorghum during the 4th millennium BC in eastern Sudan."

"Along with the recent discovery of domesticated pearl millet in eastern Mali around 2500 BC, this discovery pushes back the process for domesticating summer rainfall cereals another thousand years in the Sahel, with sorghum, providing new evidence for the earliest known native African cultigen," they said.

The research is published in the journal Current Anthropology.

Source: http://www.sci-news.com/archaeology/earliest-evidence-domesticated-sorghum-05271.html

|

This is Marlize Lombard (University of

Johannesburg) excavating

at Sibudu Cave (under

the direction of Prof Lyn Wadley, University of the Witwatersrand), about

40 km southeast of

Ballito Bay where the boy was found. The cave was intermittently occupied by humans from at least 77 000 years ago who might have been ancestral to

the Ballito boy.

Photograph: Lyn Wadley, University of the Witwatersrand.

|

Stone Age child reveals that modern humans emerged more than 300,000 years ago

28 September 2017

South Africa is well-known for its hominin fossil record. But this time, results from a study of ancient DNA presented in the September 28th First Release early online issue of Science show that the 2000-year-old remains of a boy found at Ballito Bay in KwaZulu-Natal during the 1960s, helped to rewrite human history.

Marlize Lombard, Professor of Stone Age archaeology at the University of Johannesburg, initiated collaboration with geneticists from Uppsala University in Sweden and the University of the Witwatersrand, who put together a team of experts at the Uppsala laboratory.

They reconstructed the full genome of the Ballito Bay child, together with the genomes of six other individuals from KwaZulu-Natal who lived between 2300 and 300 years ago.

Three Stone Age individuals who lived between 2300 and 1800 years ago were found to be genetically related to the descendants of Khoe-San groups living in southern Africa today. The remains of the other four individuals who lived 500-300 years ago during the Iron Age, were genetically related to present-day South Africans of West African descent.

Because the boy from Ballito Bay was of hunter-gatherer descent, living at a time before migrants from further north in Africa reached South African shores, his DNA could be used to estimate the split between modern humans and earlier human groups as occurring between 350 000 and 260 000 years ago. "This means that modern humans emerged earlier than previously thought", says Mattias Jakobsson, population geneticist at Uppsala University, who headed the project together with Marlize Lombard from the University of Johannesburg.

The 350 000 to 260 000 years estimate also coincides with the Florisbad skull, who was a contemporary of the small-brained Homo naledi in South Africa. "It now seems that at least two or three Homo species occupied the southern African landscape during this time, which also represents the early phases of the Middle Stone Age", says Lombard.

Cumulatively, the fossil, ancient DNA and archaeological records indicate that the transition from archaic to modern humans might not have occurred in only one place in Africa. Instead, regions including southern and northern Africa (as recently reported) probably played a role. "Thus, both palaeo-anthropological and genetic evidence increasingly points to multiregional origins of anatomically modern humans in Africa, i.e. Homo sapiens did not originate in one place in Africa, but might have evolved from older forms in several places on the continent with gene flow between groups from different places", says Carina Schlebusch.

These findings from South Africa shed new light on our species' deep African history and show that there is still much more to learn about our process of becoming modern humans. The results of this study also emphasise that the interplay between genetics and archaeology has an increasingly important role to play.

Source: https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-09/uoj-sac092817.php

|

Mount Hora in Malawi,

where the oldest DNA in

the study, from a woman who lived more than

8,000 years ago, was obtained.

Credit: Jessica C. Thompson/Emory

University

|

Ancient human DNA in sub-Saharan Africa lifts veil on prehistory

21 September 2017

The first large-scale study of ancient human DNA from sub-Saharan Africa opens a long-awaited window into the identity of prehistoric populations in the region and how they moved around and replaced one another over the past 8,000 years.

The findings, published Sept. 21 in Cell by an international research team led by Harvard Medical School, answer several longstanding mysteries and uncover surprising details about sub-Saharan African ancestry - including genetic adaptations for a hunter-gatherer lifestyle and the first glimpses of population distribution before farmers and animal herders swept across the continent about 3,000 years ago.

"The last few thousand years were an incredibly rich and formative period that is key to understanding how populations in Africa got to where they are today," said David Reich, professor of genetics at HMS and a senior associate member of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. "Ancestry during this time period is such an unexplored landscape that everything we learned was new."

Reich shares senior authorship of the study with Ron Pinhasi of the University of Vienna and Johannes Krause of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and the University of Tübingen in Germany.

"Ancient DNA is the only tool we have for characterizing past genomic diversity. It teaches us things we don't know about history from archaeology and linguistics and can help us better understand present-day populations," said Pontus Skoglund, a postdoctoral researcher in the Reich lab and the study's first author. "We need to ensure we use it for the benefit of all populations around the world, perhaps especially Africa, which contains the greatest human genetic diversity in the world but has been underserved by the genomics community."

Long time coming

Although ancient-DNA research has revealed insights into the population histories of many areas of the world, delving into the deep ancestry of African groups wasn't possible until recently because genetic material degrades too rapidly in warm, humid climates.

Technological advances - including the discovery by Pinhasi and colleagues that DNA persists longer in small, dense ear bones - are now beginning to break the climate barrier. Last year, Reich and colleagues used the new techniques to generate the first genome-wide data from the earliest farmers in the Near East, who lived between 8,000 and 12,000 years ago.

In the new study, Skoglund and team, including colleagues from South Africa, Malawi, Tanzania and Kenya, coaxed DNA from the remains of 15 ancient sub-Saharan Africans. The individuals came from a variety of geographic regions and ranged in age from about 500 to 8,500 years old.

The researchers compared these ancient genomes - along with the only other known ancient genome from the region, previously published in 2015 - against those of nearly 600 present-day people from 59 African populations and 300 people from 142 non-African groups.

With each analysis, revelations rolled in.

"We are peeling back the first layers of the agricultural transition south of the Sahara," said Skoglund. "Already we can see that there was a whole different landscape of populations just 2,000 or 3,000 years ago."

Genomic time-lapse

Almost half of the team's samples came from Malawi, providing a series of genomic snapshots from the same location across thousands of years.

The time-series divulged the existence of an ancient hunter-gatherer population the researchers hadn't expected.

When agriculture spread in Europe and East Asia, farmers and animal herders expanded into new areas and mixed with the hunter-gatherers who lived there. Present-day populations thus inherited DNA from both groups.

The new study found evidence for similar movement and mixing in other parts of Africa, but after farmers reached Malawi, hunter-gatherers seem to have disappeared without contributing any detectable ancestry to the people who live there today.

"It looks like there was a complete population replacement," said Reich. "We haven't seen clear evidence for an event like this anywhere else."

The Malawi snapshots also helped identify a population that spanned from the southern tip of Africa all the way to the equator about 1,400 years ago before fading away. That mysterious group shared ancestry with today's Khoe-San (or Khoisan) people in southern Africa and left a few DNA traces in people from a group of islands thousands of miles away, off the coast of Tanzania.

"It's amazing to see these populations in the DNA that don't exist anymore," said Reich. "It's clear that gathering additional DNA samples will teach us much more."

"The Khoe-San are such a genetically distinctive people, it was a surprise to find a closely related ancestor so far north just a couple of thousand years ago," Reich added.

The new study also found that West Africans can trace their lineage back to a human ancestor that may have split off from other African populations even earlier than the Khoe-San.

Missing links

The research similarly shed light on the origins of another unique group, the Hadza people of East Africa.

"They have a distinct appearance, language and genetics, and some people speculated that, like the Khoe-San, they might represent a very early diverging group from other African populations," said Reich. "Our study shows that instead, they're somehow in the middle of everything."

The Hadza, according to genomic comparisons, are today more closely related to non-Africans than to other Africans. The researchers hypothesize that the Hadza are direct descendants of the group that migrated out of Africa, and possibly spread within Africa as well, after about 50,000 years ago.

Another discovery lay in wait in East Africa.

Scientists had predicted the existence of an ancient population based on the observation that present-day people in southern Africa share ancestry with people in the Near East. The 3,000-year-old remains of a young girl in Tanzania provided the missing evidence.

Reich and colleagues suspect that the girl belonged to a herding population that contributed significant ancestry to present-day people from Ethiopia and Somalia down to South Africa. The ancient population was about one-third Eurasian, and the researchers were able to further pinpoint that ancestry to the Levant region.

"With this sample in hand, we can now say more about who these people were," said Skoglund.

The finding put one mystery to rest while raising another: Present-day people in the Horn of Africa have additional Near Eastern ancestry that can't be explained by the group to which the young girl belonged.

Natural selection

Finally, the study took a first step in using ancient DNA to understand genetic adaptation in African populations.

It required "squeezing water out of a stone" because the researchers were working with so few ancient samples, said Reich, but Skoglund was able to identify two regions of the genome that appear to have undergone natural selection in southern Africans.

One adaptation increased protection from ultraviolet radiation, which the researchers propose could be related to life in the Kalahari Desert. The other variant was located on genes related to taste buds, which the researchers point out can help people detect poisons in plants.

The researchers hope that their study encourages more investigation into the diverse genetic landscape of human populations in Africa, both past and present. Reich also said he hopes the work reminds people that African history didn't end 50,000 years ago when groups of humans began migrating into the Near East and beyond.

"The late Stone Age in Africa is like a black hole, research-wise," said Reich. "Ancient DNA can address that gap."

Source: https://phys.org/news/2017-09-ancient-human-dna-sub-saharan-africa.html

|

Partial upper jaw of Australopithecus anamensis, a primitive hominin, recovered from

the bone bed excavated

at the Allia Bay site.

Photo courtesy of Meave Leakey, PhD

|

When ancient fossil DNA isn't available, ancient glycans may help trace human evolution

11September 2017

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA - SAN DIEGO - Ancient DNA recovered from fossils is a valuable tool to study evolution and anthropology. Yet ancient fossil DNA from earlier geological ages has not been found yet in any part of Africa, where it's destroyed by extreme heat and humidity. In a potential first step at overcoming this hurdle, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine and Turkana Basin Institute in Kenya have discovered a new kind of glycan - a type of sugar chain - that survives even in a 4 million-year-old animal fossil from Kenya, under conditions where ancient DNA does not.

While ancient fossils from hominins (human ancestors and extinct relatives) are not yet available for glycan analysis, this proof-of-concept study, published September 11 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, may set the stage for unprecedented explorations of human origins and diet.

"In recent decades, many new hominin fossils were discovered and considered to be the ancestors of humans," said Ajit Varki, MD, Distinguished Professor of Medicine and Cellular and Molecular Medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine. "But it's not possible that all gave rise to modern humans - it's more likely that there were many human-like species over time, only one from which we descended. This new type of glycan we found may give us a better way to investigate which lineage is ours, as well as answer many other questions about our evolution, and our propensity to consume red meat."

Glycans are complex sugar chains on the surfaces of all cells. They mediate interaction between cells and the environment, and often serve as docking sites for pathogens. For millions of years, the common ancestors of humans and other apes shared a particular glycan known as Neu5Gc. Then, for reasons possibly linked to a malarial parasite that exploited Neu5Gc as a means to establish infection, a mutation that probably occurred between 2 and 3 million years ago inactivated the human gene encoding the enzyme that makes the molecule. The loss of Neu5Gc amounted to a radical molecular makeover of human ancestral cell surfaces and might have created a fertility barrier that expedited the divergence of the lineage leading to humans.

Today, chimpanzees and most other mammals still produce Neu5Gc. In contrast, only trace amounts can be detected in human blood and tissue—not because we make Neu5Gc, but, according to a previous study by Varki's team, because we accumulate the glycan when eating Neu5Gc rich red meat. Humans mount an immune response to this non-native Neu5Gc, possibly aggravating diseases such as cancer.

In their latest study, Varki and team found that, as part of its natural breakdown, a signature part of Neu5Gc is also incorporated into chondroitin sulfate (CS), an abundant component in bone. They detected this newly discovered molecule, called Gc-CS, in a variety of mammalian samples, including easily detectable amounts in chimpanzee bones and mouse tissues.

Like Neu5Gc, they found that human cells and serum have only trace amounts of Gc-CS - again, likely from red meat consumption. The researchers backed up that assumption with the finding that mice engineered to lack Neu5Gc and Gc-Cs (similar to humans) had detectable Gc-CS only when fed Neu5Gc-containing chow.

Curious to see how stable and long-lasting Gc-CS might be, Varki bought a relatively inexpensive 50,000-year-old cave bear fossil at a public fossil show and took it back to the lab. Despite its age, the fossil indeed contained Gc-CS.

That's when Varki turned to a long-time collaborator-paleoanthropologist and famed fossil hunter Meave Leakey, PhD, of Turkana Basin Institute of Kenya and Stony Brook University. Knowing that researchers need to make a very strong case before they are given precious ancient hominin fossil samples, even for DNA analysis, Leakey recommended that the researchers first prove their method by detecting Gc-CS in even older animal fossils. To that end, with the permission of the National Museums of Kenya, she gave them a fragment of a 4-million-year-old fossil from a buffalo-like animal recovered in the excavation of a bone bed at Allia Bay, in the Turkana Basin of northern Kenya. Hominin fossils were also recovered from the same horizon in this bone bed.

Varki and team were still able to recover Gc-CS in these much older fossils. If they eventually find Gc-Cs in ancient hominin fossils as well, the researchers say it could open up all kinds of interesting possibilities.

"Once we've refined our technique to the point that we need smaller sample amounts and are able to obtain ancient hominin fossils from Africa, we may eventually be able to classify them into two groups - those that have Gc-CS and those that do not. Those that lack the molecule would mostly likely belong to the lineage that led to modern humans," said Varki, who is also adjunct professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and co-director of the UC San Diego/Salk Center for Academic Research and Training in Anthropogeny (CARTA).

In a parallel line of inquiry, Varki hopes Gc-CS detection will also reveal the point in evolution when humans began consuming large amounts of red meat.

"It's possible we'll one day find three groups of hominin fossils - those with Gc-CS before the human lineage branched off, those without Gc-CS in our direct lineage, and then more recent fossils in which trace amounts of Gc-CS began to reappear when our ancestors began eating red meat," Varki said. "Or maybe our ancestors lost Gc-CS more gradually, or only after we began eating red meat. It will be interesting to see, and we can begin asking these questions now that we know we can reliably find Gc-CS in ancient fossils in Africa."

Leakey is also hopeful about the role Gc-CS could play in the future, as an alternative to current approaches.

"Because DNA rapidly degrades in the tropics, genetic studies are not possible in fossils of human ancestors older than only a few thousand years," she said. "Therefore such ancient glycan studies have the potential to provide a new and important method for the investigation of human origins."

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/summer-2017/article/when-ancient-fossil-dna-isn-t-available-ancient-glycans-may-help-trace-human-evolution

|

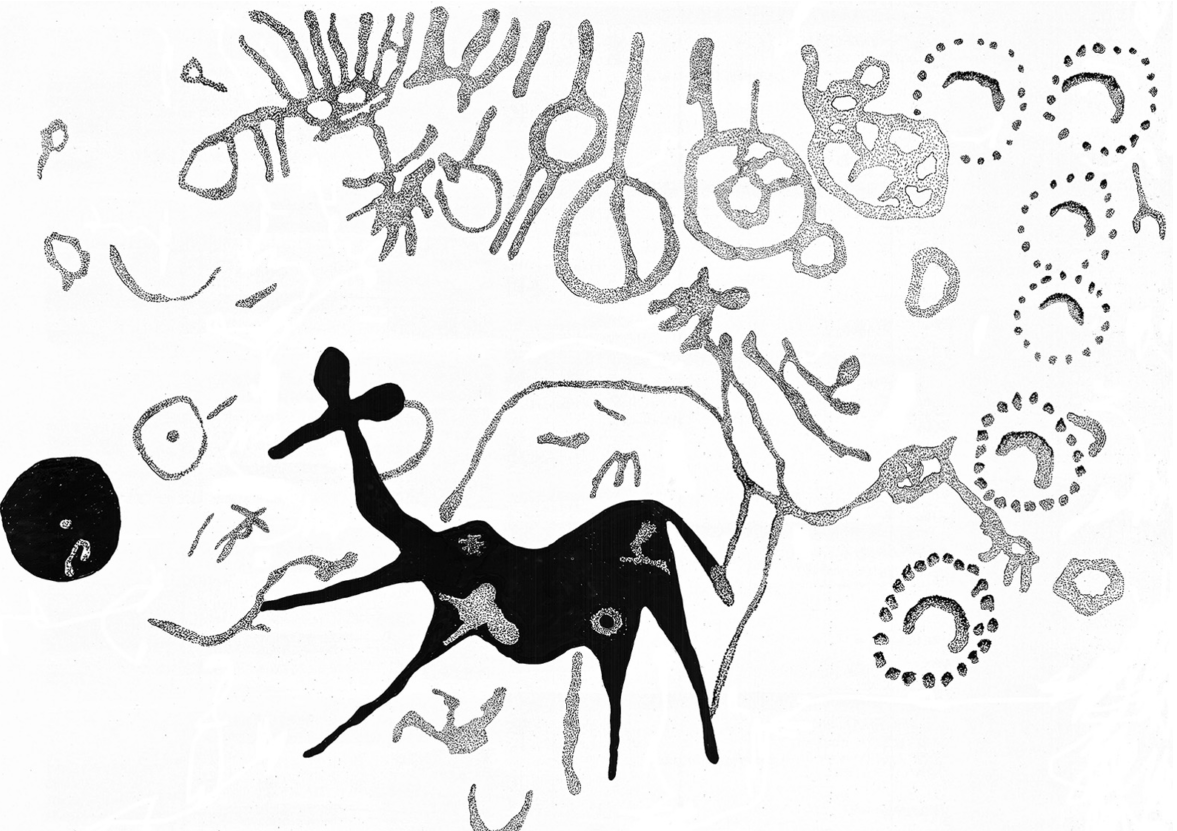

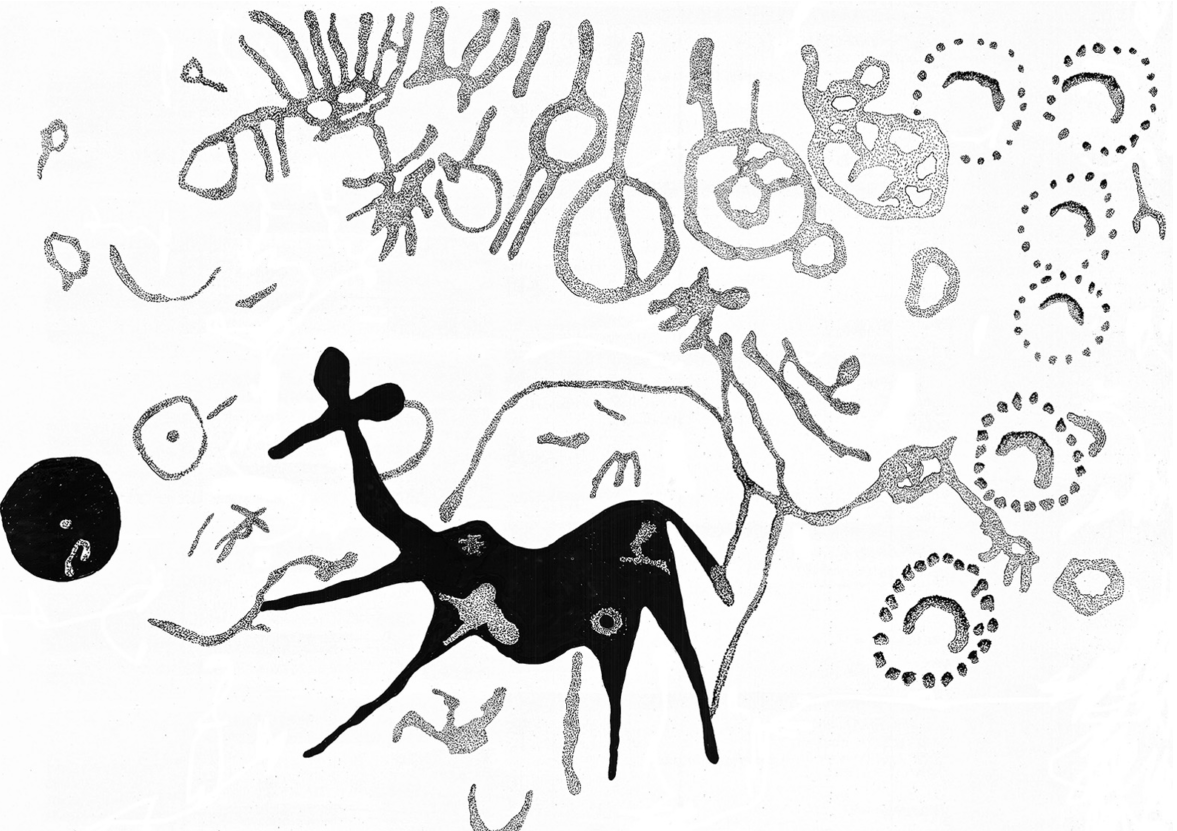

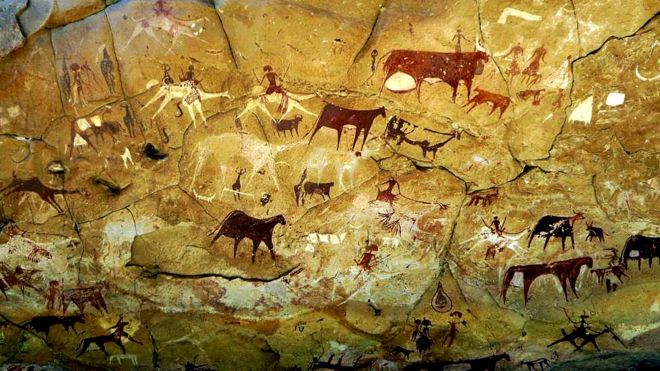

The dancing Kudu sheds light on ancient rituals.

John Kinahan/Figure 3. Antiquity doi:10.15184/aqy.2017.48

|

Rock art found in Namib Desert reveals ancient initiation rituals led by shamans

9 August 2017

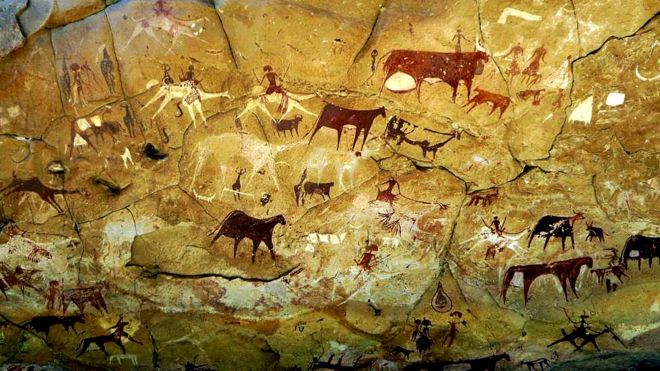

In the Namib Desert, a long arid stretch that extends for 2,000 km on the south-western coast of Africa, ancient rock art is revealing tantalising clues about the ancient hunter-gatherer societies that lived in the region thousands of years ago.

The Namib Desert Archaeological Survey is the largest area study ever undertaken in Namibia, documenting evidence of human responses to climatic shifts and the creation of a unique culture in a hyper-arid environment. Among the most remarkable archaeological features that have been investigated is the wealth of art that bears witness to the rich spiritual beliefs of hunter-gatherers and the crucial role played by shamans in their communities.

Perhaps one of the most intriguing engravings is that of a female antelope, known as a kudu. It is no more than 3,000 years old, and in a study now published in the journal Antiquity, archaeologist John Kinahan explains that it's a very important piece of rock art to understand the initiation rituals that took place in the past to help young girls in the transition to womanhood.

"Part of my work in the Namib Desert is to look for evidence of what ceremonies might have taken place here in the past. Forty years ago, I came across this image of a kudu, which is engraved with an unusual technique of rock polishing, and I was struck by it," Kinahan told IBTimes UK. "My recent investigations suggest the female kudu imagery was central to ancient initiation rituals, with this animal acting as a metaphor for positive social values."

The kudu as an example to follow

In the region, young girls in ancient hunter-gatherer societies are thought to have been brought to isolated rock shelters during initiation rituals. There, they were instructed by female relatives about how they should behave as women. The engraved panel on which the kudu is depicted also features images that represent these ritual seclusion shelters used by the young initiates. The archaeologist was also able to identify a stone circle in the vicinity of the rock panel - the remains of one of the shelters.

The study points out that the female kudu on the rock shows an array of ritualistic features. The position it is depicted in resembles the position taken by women when they grind grain and grass seeds and as such, he believes there is a clear parallel to be made between women and kudus.

Furthermore, the kudu is pictured here with a distended belly to indicate pregnancy. This depiction suggests that womanhood was linked to fertility for the ancient people who created the rock art.

"It is possible that the sociable characteristics of the female kudu were given as example to follow to young girls who prepared to become women. Kudus are docile and sociable, they look after the youngsters all together and collaborate without the males. These characteristics were probably seen as desirable for women to have. The female kudu was likely incorporated into the imagery of the initiation ceremony to put girls on the path to womanhood," Kinahan hypothesised.

The archaeologist believes that these ancient initiation rituals can only be understood if they are replaced in the context of the shamanic belief system, which was so important to the ancient hunter-gatherer societies of the Namib desert.

Shamans would have played a crucial role during such ceremonies. It is likely that these powerful figure of authorities were the ones that created the kudu engraving and that led the ceremonies that would have turned young girls into women.

Source: http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/rock-art-found-namib-desert-reveals-ancient-initiation-rituals-led-by-shamans-1632438

|

View from the Canopy

Floor in the Cloud Forest Sanctuary, Xalapa,

Mexico. Despite previous notions of tropical forests

as 'green deserts' not suitable for human habitation it is now clear that human occupation

and modification of these habitats occurred as far back as 45,000 years

ago. As our species expanded into these settings beyond Africa, they burnt vegetation to maintain resources patches and practiced specialized, sustainable hunting of select animals such as primates.

Credit: Patrick Roberts

|

Humans have been altering tropical forests for at least 45,000 years

3 August 2017

MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR THE SCIENCE OF HUMAN HISTORY - The first review of the global impact of humans on tropical forests in the ancient past shows that humans have been altering these environments for at least 45,000 years. This counters the view that tropical forests were pristine natural environments prior to modern agriculture and industrialization. The study, published today in Nature Plants, found that humans have in fact been having a dramatic impact on such forest ecologies for tens of thousands of years, through techniques ranging from controlled burning of sections of forest to plant and animal management to clear-cutting. Although previous studies had looked at human impacts on specific tropical forest locations and ecosystems, this is the first to synthesize data from all over the world.

The paper, by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Liverpool John Moores University, University College London, and École française d'Extrême-Orient, covered three distinct phases of human impact on tropical forests, roughly correlating to hunting and gathering activities, small-scale agricultural activities, and large-scale urban settlements.

Big impacts of small hunter-gatherer groups

In the deep past, groups of hunter-gatherers appear to have burned areas of tropical forests, in particular in Southeast Asia as early as 45,000 years ago, when modern humans first arrived there. There is evidence of similar forest burning activities in Australia and New Guinea. By clearing parts of the forest, humans were able to create more of the "forest-edge" environments that encouraged the presence of animals and plants that they liked to eat.

There is also evidence, though still debated, that these human activities contributed to the extinction of forest megafauna in the Late Pleistocene (approximately 125,000 to 12,000 years ago), such as the giant ground sloth, forest mastodons, and now-extinct large marsupials. These extinctions had significant impacts on forest density, plant species distributions, plant reproductive mechanisms, and life-cycles of forest stand, that have persisted to the present day.

Farming the forest

The earliest evidence for farming in tropical forests is found in New Guinea, where humans were tending yam, banana and taro by the Early-Mid Holocene (10,000 years ago). Early farming efforts in tropical forests, supplemented by hunting and gathering, had significant consequences. Humans domesticated forest plants and animals, including sweet potato, chili pepper, black pepper, mango, banana and chickens, altering the forest ecologies and contributing significantly to global cuisine today.

In general, when groups employed indigenous tropical forest agricultural strategies based on local plants and animals, these did not result in significant or lasting damage to the environment. "Indeed, most communities entering these habitats were initially at low population densities and appear to have developed subsistence systems that were tuned to their particular environments," states Dr. Chris Hunt of Liverpool John Moores University, a co-author of the study.

However, as agricultural intensity increased, particularly when external farming practices were introduced into tropical forests and island environments, the effects became less benign. When agriculturalists bringing pearl millet and cattle moved to the area of tropical forests in western and central Africa about 2,400 years ago, significant soil erosion and forest burning occurred. Similarly, in Southeast Asia, large areas of the tropical forests were burned and cleared from c. 4,000 years ago following the arrival of rice and millet farming. For example, the increase in demand for palm oil has led to clear-cutting of tropical forests to make room for palm plantations. "These practices, which induce rampant clearance, reduce biodiversity, provoke soil erosion, and render landscapes more susceptible to the outbreak of wild fires, represent some of the greatest dangers facing tropical forests," notes Hunt.

Sprawling cities in the jungle

Despite previous notions of tropical forests as "green deserts" not suitable for human habitation, recent discoveries using new technologies have shown that ancient populations created vast urban settlements in these habitats. New data, including surveys made with canopy-penetrating Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) mapping, have revealed human settlement in the Americas and Southeast Asia on a scale that was previously unimagined. "Indeed, extensive settlement networks in the tropical forests of Amazonia, Southeast Asia, and Mesoamerica clearly persisted many times longer than more recent industrial and urban settlements of the modern world have so far been present in these environments," notes Dr. Patrick Roberts of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, lead author of the paper.

Lessons can be learned from how these ancient urban centers dealt with environmental challenges that are still faced by modern cities in these areas today. Soil erosion and the failure of agricultural systems necessary to feed a large population are problems encountered by large urban centers, past and present. In some Mayan areas, urban populations "gardened" the forest, by planting a variety of complementary food crops in and around the existing forest rather than clearing it. On the other hand, other groups appear to have over-stressed their local environments through forest clearing and monoculture planting of corn, which, in combination with climate change, resulted in dramatic population declines.

Another interesting finding is that ancient forest cities showed the same tendency towards sprawl as is now being recommended by the architects of modern cities in these zones. In some cases these extensive urban fringes appear to have provided a sort of buffer-zone, helping to protect the urban centers from the effects of climate change and providing food security and accessibility. "Diversification, decentralization and 'agrarian urbanism' appear to have contributed to overall resilience," states Dr. Damian Evans, a co-author of the paper. These ancient forest suburbs are now being studied as potential models of sustainability for modern cities.

Lessons for the future

The global data compiled for this paper shows that a pristine, untouched tropical forest ecosystem does not exist - and has not existed for tens of thousands of years. There is no ideal forest environment that modern conservationists can look to when setting goals and developing a strategy for forest conservation efforts. Rather, an understanding of the archaeological history of tropical forests and their past manipulation by humans is crucial in informing modern conservation efforts. The researchers recommend an approach that values the knowledge and cooperation of the native populations that live in tropical forests. "Indigenous and traditional peoples - whose ancestors' systems of production and knowledge are slowly being decoded by archaeologists - should be seen as part of the solution and not one of the problems of sustainable tropical forest development," states Roberts. The researchers also emphasize the importance of disseminating the information learned from archaeology to other disciplines. By working together, these groups can help to establish a better understanding of the tropical forest environments and how best to protect them.

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/summer-2017/article/humans-have-been-altering-tropical-forests-for-at-least-45-000-years

|

The Klipdrift Shelter in

the De Hoop Nature Reserve in the southern Cape, South Africa,

where Howiesons Poort deposits were excavated.

Credit: Stephen Alvarez

|

Cultural flexibility was key for early humans to survive extreme dry periods in southern Africa

26 July 2017

University of the Witwatersrand - The flexibility and ability to adapt to changing climates by employing various cultural innovations allowed communities of early humans to survive through a prolonged period of pronounced aridification.

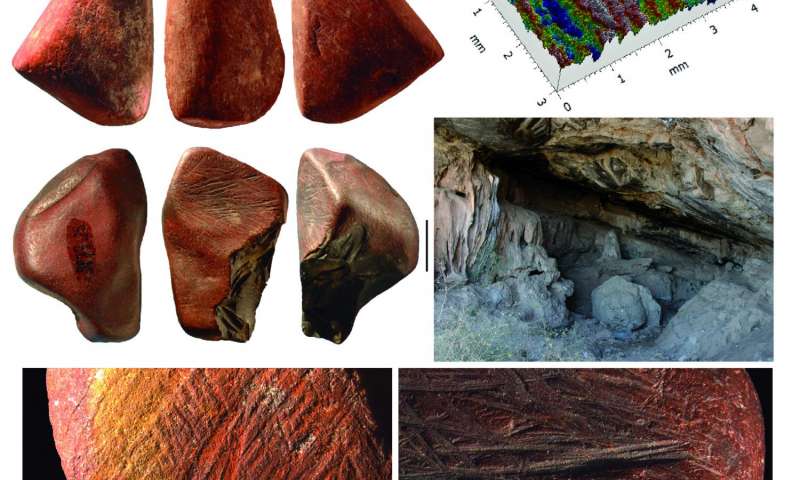

The early human techno-tradition, known as Howiesons Poort (HP), associated with Homo sapiens who lived in southern Africa about 66,000 to 59,000 years ago indicates that during this period of pronounced aridification they developed cultural innovations that allowed them to significantly enlarge the range of environments they occupied.

This cultural flexibility may have been the key to success for modern humans, says a team of international researchers, made up of archaeologists, paleo climatologists, and climate modellers from the French CNRS1 and the EPHE PSL Research University, Bergen University as well as Wits University. Their research was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

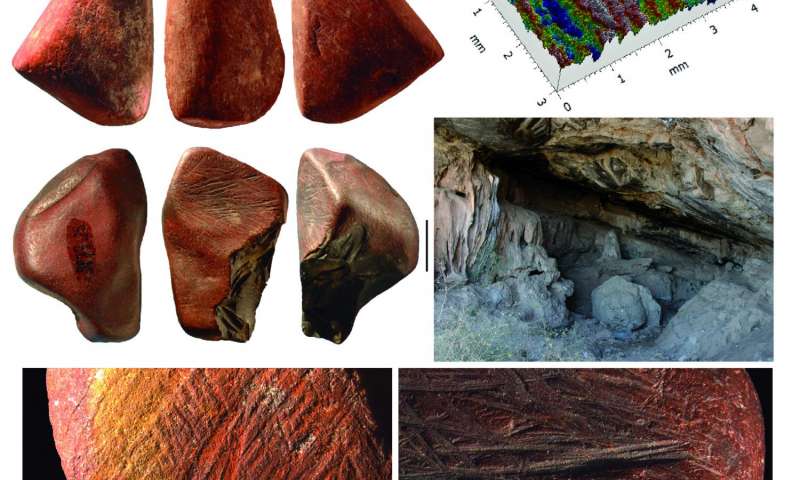

"The most distinct of the many cultural innovations in the HP culture were the invention of the bow and arrow, different methods of heating raw materials (stone) before knapping to produce arrow heads, engraving ostrich eggshells with elaborate patterns, intensive use of hearths and relatively intense hunting and gathering practices," says Professor Christopher Henshilwood, one of the team members from Wits and Bergen Universities.

Howiesons Poort is a techno-tradition in the Middle Stone Age in Africa named after the Howieson's Poort Shelter archaeological site near Grahamstown in South Africa. It lasted around 5,000 years between roughly 65,800 and 59,500 years ago.

Using paleo climatic data and paleo climatic simulations, the researchers of the current study found that the HP tradition developed during a period of pronounced aridity.

This paleo climatic data and the distribution of archaeological sites associated with the HP, as well of that of the Still Bay tradition, which existed in the same environments about 5,000 years before (76,000 to 71,000 years ago), enabled the researchers to model the emergence of these traditions with two predictive algorithms that permitted them to reconstruct the ecological niche associated with each tradition and determine whether these niches differed significantly through time.

The results clearly indicate that HP populations were capable, despite the pronounced aridity that characterised the period in which they lived, to exploit territories and ecosystems that the preceding Still Bay people did not occupy.

While the Still Bay era is also characterised by highly innovative technologies - including engraving of ochre, use of personal ornaments, manufacture of highly stylised bone tools, heating silcrete (red rock) to produce better material for knapping bifacial points (spear points) using hard hammer and finally pressure flaking technology - the research team points out that HP's ecological niche expansion coincides with the development of technological innovations that were both efficient and more flexible than those of the Still Bay.

"It seems from the little evidence that we have that the population of Homo sapiens in southern Africa was considerably larger during the Howiesons Poort period," says Henshilwood.

"There are many more HP sites than Still Bay sites in southern Africa and their location is widespread across southern Africa. Note that neither the Still Bay or HP is found outside of southern Africa."

Henshilwood says the Still Bay people did not disappear. There just seems to be a gap between 72,000 years ago to 66,000 years ago, where there is almost no evidence of any people in southern Africa.

This study, which documents the oldest known case of an eco-cultural niche expansion, demonstrates that the processes that allowed our species to develop modern behaviours must be examined at regional scales and in conjunction with past climatic data.

About early human development:

The emergence of our species (Homo sapiens) in Africa, at least 260,000 years ago, was not immediately accompanied by the development of behavioural characteristics of more recent prehistoric and historically documented populations. For tens of thousands of years after their emergence (anatomically), modern human populations in Africa continued to use technologies that differed little from those of the non-modern populations that preceded them or that inhabited other regions both inside and outside the African continent.

A number of archaeological discoveries during the past twenty years have shown that from at least 100,000 years ago some populations in Africa, especially those in southern Africa, made pigmented compounds, wore personal ornaments, made abstract engravings, and manufactured bone tools. It is within this period, and those that follow, that archaeologists are able to recognize distinct techno- traditions, to determine with a certain degree of precision their age, and place these time periods within their proper climatic contexts.

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/fall-2017/article/cultural-flexibility-was-key-for-early-humans-to-survive-extreme-dry-periods-in-southern-africa

|

|

In saliva, clues to a 'ghost' species of ancient human

21 July 2017

In saliva, scientists have found hints that a "ghost" species of archaic humans may have contributed genetic material to ancestors of people living in Sub-Saharan Africa today.

The research adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that sexual rendezvous between different archaic human species may not have been unusual.

Past studies have concluded that the forebears of modern humans in Asia and Europe interbred with other early hominin species, including Neanderthals and Denisovans. The new research is among more recent genetic analyses indicating that ancient Africans also had trysts with other early hominins.

"It seems that interbreeding between different early hominin species is not the exception—it's the norm," says Omer Gokcumen, PhD, an assistant professor of biological sciences in the University at Buffalo College of Arts and Sciences.

"Our research traced the evolution of an important mucin protein called MUC7 that is found in saliva," he says. "When we looked at the history of the gene that codes for the protein, we see the signature of archaic admixture in modern day Sub-Saharan African populations."

The research was published on July 21 in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution. The study was led by Gokcumen and Stefan Ruhl, DDS, PhD, a professor of oral biology in UB's School of Dental Medicine.

A tantalizing clue in saliva

The scientists came upon their findings while researching the purpose and origins of the MUC7 protein, which helps give spit its slimy consistency and binds to microbes, potentially helping to rid the body of disease-causing bacteria.

As part of this investigation, the team examined the MUC7 gene in more than 2,500 modern human genomes. The analysis yielded a surprise: A group of genomes from Sub-Saharan Africa had a version of the gene that was wildly different from versions found in other modern humans.

The Sub-Saharan variant was so distinctive that Neanderthal and Denisovan MUC7 genes matched more closely with those of other modern humans than the Sub-Saharan outlier did.

"Based on our analysis, the most plausible explanation for this extreme variation is archaic introgression - the introduction of genetic material from a 'ghost' species of ancient hominins," Gokcumen says. "This unknown human relative could be a species that has been discovered, such as a subspecies of Homo erectus, or an undiscovered hominin. We call it a 'ghost' species because we don't have the fossils."

Given the rate that genes mutate during the course of evolution, the team calculated that the ancestors of people who carry the Sub-Saharan MUC7 variant interbred with another ancient human species as recently as 150,000 years ago, after the two species' evolutionary path diverged from each other some 1.5 to 2 million years ago.

Why MUC7 matters

The scientists were interested in MUC7 because in a previous study they showed that the protein likely evolved to serve an important purpose in humans.

In some people, the gene that codes for MUC7 holds six copies of genetic instructions that direct the body to build parts of the corresponding protein. In other people, the gene harbors only five sets of these instructions (known as tandem repeats).

Prior studies by other researchers found that the five-copy version of the gene protected against asthma, but Gokcumen and Ruhl did not see this association when they ran a more detailed analysis.

The new study did conclude, however, that MUC7 appears to influence the makeup of the oral microbiome, the collection of bacteria within the mouth. The evidence for this came from an analysis of biological samples from 130 people, which found that different versions of the MUC7 gene were strongly associated with different oral microbiome compositions.

"From what we know of MUC7, it makes sense that people with different versions of the MUC7 gene could have different oral microbiomes," Ruhl says. "The MUC7 protein is thought to enhance the ability of saliva to bind to microbes, an important task that may help prevent disease by clearing unwanted bacteria or other pathogens from the mouth."

More information: Duo Xu et al, Archaic hominin introgression in Africa contributes to functional salivary MUC7 genetic variation, Molecular Biology and Evolution (2017). DOI: 10.1093/molbev/msx206

Source: https://phys.org/news/2017-07-saliva-clues-ghost-species-ancient.html

|

A view of the Lake Turkana environment as it exists today. AdamPG, Wikimedia Commons

|

Animals, not drought, shaped our ancestors' environment

26 June 2017

The shores of Lake Turkana, in Kenya, are dry and inhospitable, with grasses as the dominant plant type. It hasn't always been that way. Over the last four million years, the Omo-Turkana basin has seen a range of climates and ecosystems, and has also seen significant steps in human evolution. Scientists previously thought that long-term drying of the climate contributed to the growth of grasslands in the area and the rise of large herbivores, which in turn may have shaped how humans developed. It's tough to prove that hypothesis, however, because of the difficulty of reconstructing four million years of climate data.

Researchers from the University of Utah have found a better way. By analyzing isotopes of oxygen preserved in herbivore teeth and tusks, they can quantify the aridity of the region and compare it to indicators of plant type and herbivore diet. The results, published in a study issued through the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) show that, unexpectedly, no long-term drying trend was associated with the expansion of grasses and grazing herbivores. Instead, variability in climate events, such as rainfall timing, and interactions between plants and animals may have had more influence on our ancestors' environment. This shows that the expansion of grasslands isn't solely due to drought, but more complex climate factors are at work, both for modern Africans now and ancient Africans in the Pleistocene.

Source: http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/summer-2017/article/animals-not-drought-shaped-our-ancestors-environment

|

These are the remains of a 12th Century mosque

|

Archaeologists in Ethiopia uncover ancient city in Harlaa

16 June 2017

A forgotten city thought to date back as far as the 10th century AD has been uncovered by a team of archaeologists in eastern Ethiopia.

Artefacts from Egypt, India and China have been found in the city in the Harlaa region.

The archaeologists also uncovered a 12th Century mosque which is similar to those found in Tanzania and Somaliland.

Archaeologists says this proves historic connections between different Islamic communities in Africa.

"This discovery revolutionises our understanding of trade in an archaeologically neglected part of Ethiopia. What we have found shows this area was the centre of trade in that region," lead archaeologist Professor Timothy Insoll from the University of Exeter said.

The team also found jewellery and other artefacts from Madagascar, the Maldives, Yemen and China.

Harlaa was a "rich, cosmopolitan" centre for jewellery making, Prof Insoll said.

"Residents of Harlaa were a mixed community of foreigners and local people who traded with others in the Red Sea, Indian Ocean and possibly as far away as the Arabian Gulf," he said.

'City of giants'

BBC Ethiopia correspondent Emmanuel Igunza says there was a local myth that the area was occupied by giants because the settlement buildings and walls were constructed with large stone blocks that could not be lifted by ordinary people.

However the archaeologists found no evidence of this.

"We have obviously disproved that, but I'm not sure they fully believe us yet," said Prof Insoll.

A statement from the team says the remains of some of the 300 people buried in the cemetery are being analysed to find out what their diet consisted of.

Further excavations are expected to be conducted next year.

A religious crossroads

Ethiopia was one of the earliest places known to be inhabited by humans. In 2015 researchers discovered jaw bones and teeth in the north-west of the country dating to between 3.3m and 3.5m years old.

Coptic Christianity was introduced from Egypt and was adopted as the religion of the Kingdom of Aksum in 333 AD. The Ethiopian church maintains that the Old Testament figure of the Queen of Sheba travelled from Aksum in northern Ethiopia to visit King Solomon in Jerusalem.

Islam arrived in Ethiopia in the 7th Century as early Muslim disciples fled persecution in Mecca. The main seat of Islamic learning in Ethiopia was Harar, which is located near Harlaa. Harar is said to be among the holiest Islamic cities and has 82 mosques, including three dating from the 10th Century, and 102 shrines, according to Unesco.

Today there are about 30m Christians and 25m Muslims in the country, according to 2007 census figures.

Source: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-40301959

|

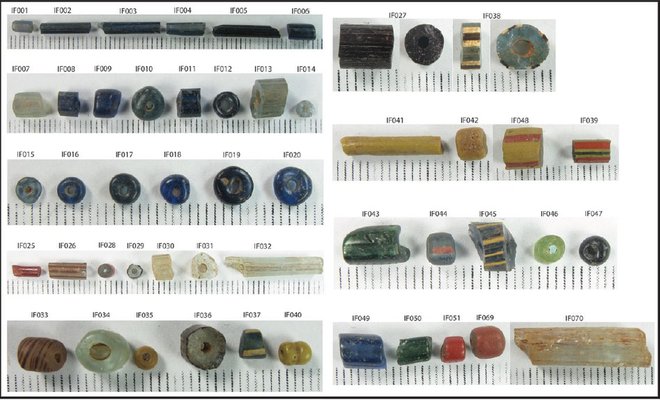

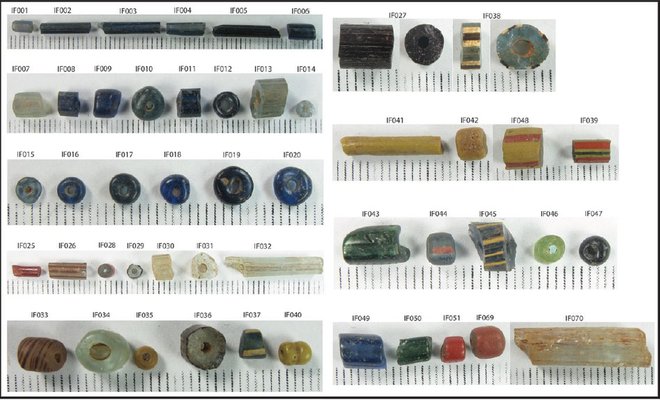

Researchers found glass beads of all colors in the ancient city of Ile-Ife. Credit: Babalola, A.B.

|

1,000-Year-Old Colored Glass Beads Discovered in West Africa

13 June 2017

A newly discovered treasure trove of more than 10,000 colorful glass beads, as well as evidence of glassmaking tools, suggests that an ancient city in southwestern Nigeria was one of the first places in West Africa to master the complex art of glassmaking, scientists reported.

The finding shows that people who lived in the ancient city of Ile-Ife learned how to make their own glass using local materials and fashion it into colorful beads, said study lead researcher Abidemi Babalola, a fellow at Harvard University's Hutchins Center for African & African American Research.

"Now we know that, at least from the 11th to 15th centuries [A.D.], there was primary glass production in sub-Saharan Africa," said Babalola, who specializes in African archaeology.

Ancient city of IIe-Ife

The ancient city of Ile-Ife was the ancestral home of the Yoruba, an ethnic group of people who live in Africa today. The Yoruba people view Ile-Ife as the mythic birthplace of several of their deities, Babalola and his colleagues wrote in the study.

Ile-Ife is also widely known for its copper alloy and terracotta heads and figurines that were made between the 12th and 15th centuries A.D., the researchers said.

Some of the figurines are decorated with glass beads on their headdresses, crowns, necklaces, armlets and anklets, the researchers said. Moreover, archaeologists have found glass beads at Ile-Ife's ancient shrines and within unearthed crucibles - ceramic containers that were used to melt glass.

Where did these glass beads come from? Most researchers speculated that the beads arrived from afar through trade, possibly from the Mediterranean area or the Middle East, and that artisans in Ile-Ife used crucibles to melt and refashion some of them into new beads, Babalola told Live Science.

But Babalola and a handful of other researchers suspected that the answer was closer to home. To find out, Babalola traveled to Igbo-Olokun, an archaeological site within Ile-Ife, and excavated several places from 2011 to 2012, searching for evidence of local glass production, he said.

Babalola discovered a treasure trove during the excavation, finding almost 13,000 beads, 812 crucible fragments, 403 fragments of ceramic cylinders (rods that were possibly used to handle the crucible lids), almost 7 lbs. (3 kilograms) of glass waste and about 14,000 potsherds, the researchers wrote in the study.

Babalola didn't find any furnaces that would have helped artisans heat the crucibles, but "the abundance of glass-production debris and the presence of vitrified clay fragments [clay with melted glass on it] indicate, however, that these areas were in, or very near, a zone of glass workshops," the researchers wrote in the study.

The majority of the beads are less than 0.2 inches (5 millimeters) across, and are colored blue, green, red, yellow or multicolored, Babalola said.

The researchers found that many of the beads, primarily the blue ones, were made "almost exclusively" from materials that are found near Igbo-Olokun, they wrote in the study. For instance, these beads had a high aluminum-oxide (also known as alumina) content, and previous researchers have pointed out that there are high-alumina sand deposits near Ile-Ife, Babalola said.

What's more, artisans might have used local ingredients, such as feldspar, to lower the heating temperature needed to melt glass in the crucibles, he said.

Glass world

The beads Babalola and his colleagues studied are called drawn beads, meaning artisans used a special technique that included using an air bubble to make the beads' holes. Craftspeople in India were making drawn glass beads as early as the fourth century B.C., but given the distance between India and modern-day Nigeria, Babalola and his colleagues propose that the West Africans developed the technique independently, he said.

However, more research is needed to support this claim, Babalola noted.

After the West African people made these beads, they traded them far and wide. Beads with the same components have been found in the upper Senegal region, including in Mali, and along the Niger River, the researchers wrote in the study.

The findings also show that West Africans were more technologically advanced than previously thought, Babalola said.

"We are talking about very sophisticated crafts," he said. "It takes someone who knows what he is doing and someone who has a very good understanding of science and technology to make this glass."

The study was published in the June issue of the journal Antiquity.

Source: https://www.livescience.com/59462-early-glassmaking-west-africa.html

|

Dr Humphris with workers at the UCL Qatar Iron and Kush Information Point in Sudan

|

Archaeological dig in Sudan unearths 'many exciting finds'

12 June 2017

When UCL Qatar archaeologist Dr Jane Humphris returns to work in the ancient city of Meroe, Sudan, later this year, she says it will feel like "going home".

Dr Humphris, who heads UCL Qatar's Sudan archaeology project, has been overseeing investigations into ancient iron production associated with Meroe, part of the Kingdom of Kush, for the last five years.

During this time, the UCL Qatar team has unearthed many exciting archaeological finds, been instrumental in involving the local community in work at Meroe, provided dedicated training to many Sudanese graduates and, earlier this year, opened the 'UCL Qatar Iron and Kush Information Point' for visitors to learn about the technological history of the area.

"You really start to become part of the local family out there," said Dr Humphris. "Over the years we've built a 'dig house' for the team at Meroe. So now, when I'm driving out to the village where our site is, it's like going home, and the people living in the area are like a big extended family."

While Meroe has been known as an ancient iron production centre for around 100 years, very little archaeology research had been done in relation to the metallurgical remains in the area until the UCL Qatar project, backed by Qatar Foundation (QF), began excavating in 2012.

"We've found very early iron production at the site as well as later iron works," said Dr Humphris, who explained that Meroe was the second capital of the Kingdom of Kush, which was a powerful African state from roughly 800BC to 350AD.

When the UCL Qatar team discovered an ancient iron production and furnace workshop at Meroe in 2014, it gave rise to the idea to build an Information Point at the site. "This was a great opportunity for us to think about doing experimental archaeology; because the best way to understand an ancient technology is to try to do it yourself."

Dr Humphris' team built a replica of the furnace workshop next to the biggest iron remains at Meroe. "We built the furnace and it worked, so we staged the area as if we'd just been smelting and developed information panels on the Kingdom of Kush, the Royal City of Meroe, as well as iron production and its importance. The idea is that people can go there anytime and learn about the site."

Dr Humphris, who has worked as an Africanist archaeologist with a specialism in iron production for more than 15 years, divides her time between working in the field in Sudan, and in the labs and at her office at UCL Qatar in Education City, Doha.

"One of the great things about being an archaeologist is that you never know what you're going to find. Every little thing we find in our trenches has the potential to be an exciting breakthrough," she said.

Like any successful archaeological project, UCL Qatar's Sudan research is dependent on the analysis of samples taken from the site. Through its collaboration with the Sudan National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums, the team has been able to bring a wide range of samples back to the material science labs in Doha for analysis.

"We've had some really nice object finds, nothing like gold or treasure, but things like a figurine that could have been a child's toy, and huge quantities of pottery that help us to examine what people might have been eating or drinking. I really like finding things that bring the human aspect into the archaeology we’re excavating."

Dr Humphris describes the labs at UCL Qatar as "almost unparalleled" in the region. "The analysis we carry out on samples here allows us to recreate and tell the story of the past. The facilities QF provides are very impressive; and it goes beyond the labs to the libraries. I’m running a project from Sudan and Qatar and we have the most amazing library at our disposal that covers everything from museums to database management to conservation."

The head of UCL Qatar research in Sudan says she is looking forward to returning to Meroe for 12 weeks from the start of October. "I always look forward to getting back to Meroe. When we're not in the field, we're busy doing analysis in Doha, so by the time we return, our understanding of everything has developed so much that we can move forward with the research questions we want to ask for our up-coming field season," she said.

Source: http://www.gulf-times.com/story/553025/Archaeological-dig-in-Sudan-unearths-many-exciting

|

The "prehistoric"

landscape of the

Sabaloka Mountains,

near the archaeological site. Petr Pokorný, 2014

|

Sudan: Mysterious holes drilled in rocks are remains of ancient shelters on the banks of the Nile River

12 June 2017

Mysterious man-made holes in rocks located on the west bank of the River Nile could be the remains of an ancient extinct type of architecture created thousands of years ago, archaeologists have said.

Working at the site of Sphinx, in central Sudan, researchers have associated these strange features with wooden pole-built structures which probably served as shelters for the people living there sometime during the Mesolithic era (between 9000 and 5000 BCE), or later.

Unusual man-made features in the rocks of North Africa are often reported during rock art surveys, but archaeologists have so far devoted little attention to them.

The study now published in the journal Antiquity focuses on a series of holes found in granite rocks. Although these rocks have been affected by natural processes over the years, these particular holes stand out.

"These holes are clearly man-made as their regular shapes and diameters suggest, they are different from natural features that appear with the weathering of the rocks. One of the first questions we get when we present the paper is how these holes were drilled," one of the study's authors, Lenka Varadzinová, a researcher at the Czech Institute of Egyptology, told IBTimes UK.

"Metal was probably not involved in the process as we find no traces of it. We can't be sure of the method used to create the holes, but what is certain is that it would have been a hell of a job, a long term investment done over a long period of time with the intention of being fixed to the place"

Experimental reconstruction

The archaeologists describe the holes saying they have a regular cylindrical shape with visibly smooth sides, a diameter of between 40 and 50 mm, and a pointed end. They are positioned at a height of about 1.3 to 3.2 metres above the present-day ground surface.

While these holes could be sign of ancient rituals associated with magic and spirituality, no firm evidence backs this up. Instead, the archaeologists believe that they were made to fulfill a more practical function. In the paper, they investigate this hypothesis further.